Here we are, a first for Momentary Cinema: ranking movies of a director. Well, the thing is that I absolutely adore the work of Hayao Miyazaki – the legendary artist, animator, writer and director from Japan – so it is not an easy task to rank his 12 feature films from worst to best. Anyway, I would like to view this list as my least favourite to my most favourite. And by least favourite, I mean I still highly recommend this film because its awesome. And by most favourite, I mean I regard this as one of the greatest films ever made. I hope that underscores the importance of this list – if you haven’t seen all these films from the anime master, you better get on to it.

12. Ponyo / Gake no Ue no Ponyo (2008)

By the time Ponyo was released, Miyazaki and Studio Ghibli were renowned the world over, and there were high expectations in the movie business. The film was released in 25 times more theatres in the US than his previous film, Howl’s Moving Castle, which tells you something. I really like the film – the story of a goldfish-humanoid who drifts out of the sea and befriends a human boy is typical magical Miyazaki fare – but it is unfortunate that one of his films must be ranked at the bottom of this list! I rate it the lowest because I think it has too much of the ‘cutsie wootsie’ going on and it doesn’t carry as much sub-textual heft as his other films. However, Miyazaki as a true artist is on display in every frame. In dreaming up the concept of this feature, he found influence in a seaside city in Fukuyama, the literary works of Natsume Sōseki, the music of Richard Wagner, Hans Christian Andersen’s ‘The Little Mermaid’, and the growing pains of his own son, Goru. It is very much his film, and it offers some breathtaking aqua-based animation.

11. Kiki’s Delivery Service / Majo no Takkyūbin (1989)

I have only watched Kiki once so it is possible I am not giving it enough credit with its low placement here. But the commitment to presenting an enlivened worldview of a young woman is impressive and is done in a way that Disney movies could never manage. Miyazaki placed a lot of admiration in his mother, whom he regarded as a strong, independent woman who brought up her family through devastating war and severe health issues. It is no surprise he envisioned the spirit of his mother in his many female characters. Kiki is a burgeoning young witch seeking to establish herself in a new city and find her niche as a flying courier. The film goes to the heart of Miyazaki’s own conscious outlook about the modern world and his desire to impart lessons to a younger generation on how to navigate life responsibly. Through Kiki’s plight, we see clearly that the toughest moments in life can come when a child becomes an adult. The setting In Kiki’s Delivery Service is beautifully rendered with inspirations stemming from the fictional European city of its source material, and the architecture of Swedish cities Stockholm and Visby, which Miyazaki and his crew visited during production. The soundtrack is also one of Joe Hisaishi’s most memorable and it fits the material perfectly.

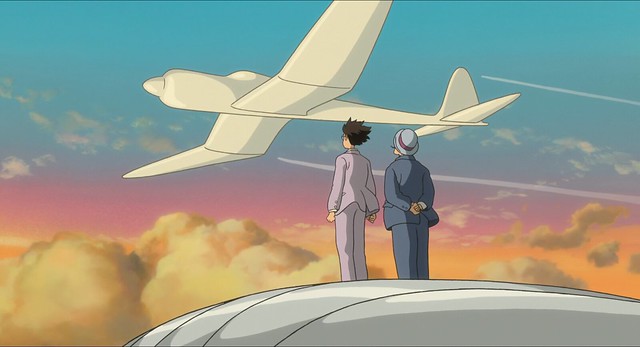

10. The Wind Rises / Kaze Tachinu (2013)

They all thought this was Miyazaki’s last film, but how silly they were! In fairness, there was a sense of a ‘swan song’ about this one – it is based on an auto-biography of Japanese aeronautical engineer Jiro Horikoshi, but in many ways, Miyazaki reflects on his own life through this life’s tale. The terror and delights of a journey from childhood to adulthood in Japan in the first half of the twentieth century is presented in extraordinarily animated form. This is a straight-up story from Miyazaki and no overt magic will you find here. But in terms of visual magic, there is plenty. In the time since his last film (Ponyo in 2008), you can see that technology had advanced to a point where Miyazaki was more comfortable with in terms of enhancing his usual hand-drawn animation. The 3D is less garish and now more refined. The visualisation of a pre-war Tokyo is mesmerising, and although the story can be quite serious and depressing, Miyazaki, who has the ability to weave truly touching narratives, ensures that The Wind Rises is ultimately a film about optimism and hope.

9. Laputa: Castle in the Sky / Tenkū no Shiro Rapyuta (1986)

Castle in the Sky was the genesis of Studio Ghibli, even though most of the people who worked on it were also involved in Miyazaki’s previous offering Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind. You could argue it starts where his previous film left off in that it explores very similar themes of ecocide and independent youth. It also shares Nausicaä’s steampunk elements such as retro-futuristic dirigibles and fighter planes. But I think the difference here is that he scales back on the dystopia and the more disturbing elements that made Nausicaä inaccessible for younger kids. By centring his story around two young orphans, he is trying to connect with a younger audience (although the long running time could be a patience-tryer) – you can see that what I find issue with in Castle in the Sky is mainly related to its comparisons with Nausicaä, which I rank much higher on this list. But it is still a brilliant anime, and it conjures up a nostalgic feeling for the animated films and TV shows of my youth. The more I watch it, the more impressed I am by the visual concepts and styles, the sounds, and the ambition shown by Miyazaki and his animators. I know movies like Akira and Ghost in the Shell take a lot of kudos from anime enthusiasts because they provide that ‘other dimension’ in terms of sci-fi steampunk-styled animation, often played out in an adults-only world of unapologetic blood-letting and violence. But Miyazaki gives us more of a human depth. His attention to detail in every scene is incredible – every character is moving and/or doing something. The action is always thrilling and entertaining, and his young protagonists are strong-willed and free, which is inspirational.

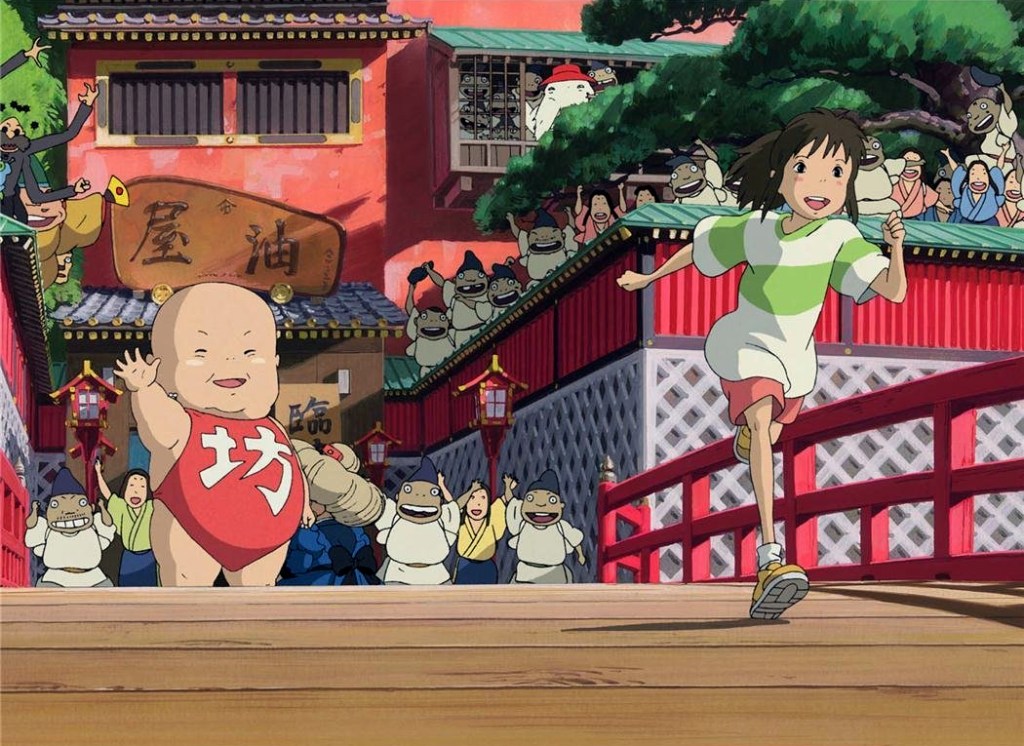

8. Spirited Away / Sen to Chihiro no Kamikakushi (2001)

For many people, Spirited Away is the film most synonymous with Miyazaki and Studio Ghibli – it won the Academy Award for Best Animated Feature and was the highest grossing Japanese film of all time for almost 20 years. I remember at the time it was released critics calling it one of the greatest movies ever made, and it continues to be cited in those GOAT lists today. It also maintains a major influence on modern-day Disney Pixar pictures, where the goal is not to be so heart-wrenching and tear-inducing anymore. You cannot deny the power of the film, but what does puzzle me is that the film is essentially a melding of previous ideas and concepts evident in Miyazaki’s many feature films, TV series, shorts and manga works leading up to this. The guy was making this amazing shit for almost 40 years before that! Regardless, it is an utterly magical fantasy, and it weaves its fascinatingly original story at a frenetic pace. Joe Hisaishi’s soundtrack is haunting, and even though 3D visuals were incorporated, some of the scenes really do defy belief. I love Miyazaki’s commitment to the Shinto-Buddhist principle that all spirits should be respected, and I admire his underlying commentary on social mores and consumerism (nods to Animal Farm are unavoidable).

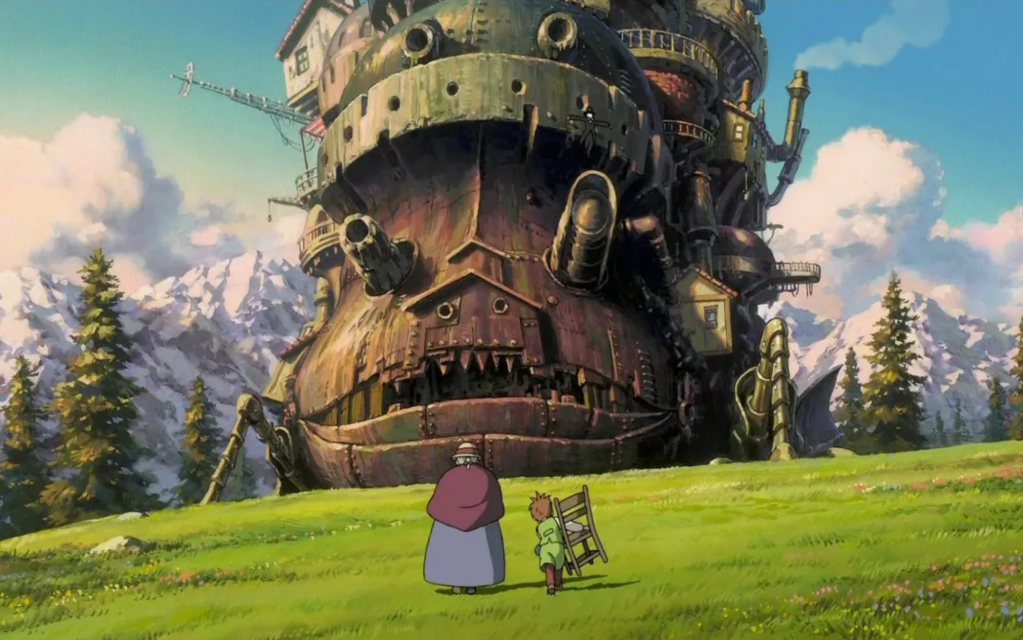

7. Howl’s Moving Castle / Hauru no Ugoku Shiro (2004)

As seen more so in his later years, Miyazaki took to adapting other works to make his films, such as here with Howl’s Moving Castle, which was a popular fantasy novel written by Diana Wynne Jones in the 1980s. Many critics found problems in the way Miyazaki tried to marry Jones’s material with his own. I have never read the novel and I am sure it is awesome, but what I see in Miyazaki’s film is a fantastic story with magnificent visuals. It is full of fascinating parts. The ’moving castle’ of the title, for example, is a centrepiece of cyberpunk curiosity and a technological wonder that Miyazaki’s art brings to life in an extraordinary way. Then you have the central character of Sophie who inhabits heart-breaking humanity – a beautiful young woman changed into an old lady by a wicked witch. Miyazaki accentuates her courage, her industry, and her inevitable heroism. You also have the usual slew of madcap characters, and the background imagery, inspired by architecture in eastern France, is incredible. There are also strong ideals around pacifism, which was central to Miyazaki’s reasoning for making this film – he claimed he wanted to make a statement against the US’s imperial invasion of Iraq. It is quite different from his other films but it is an equal delight to watch.

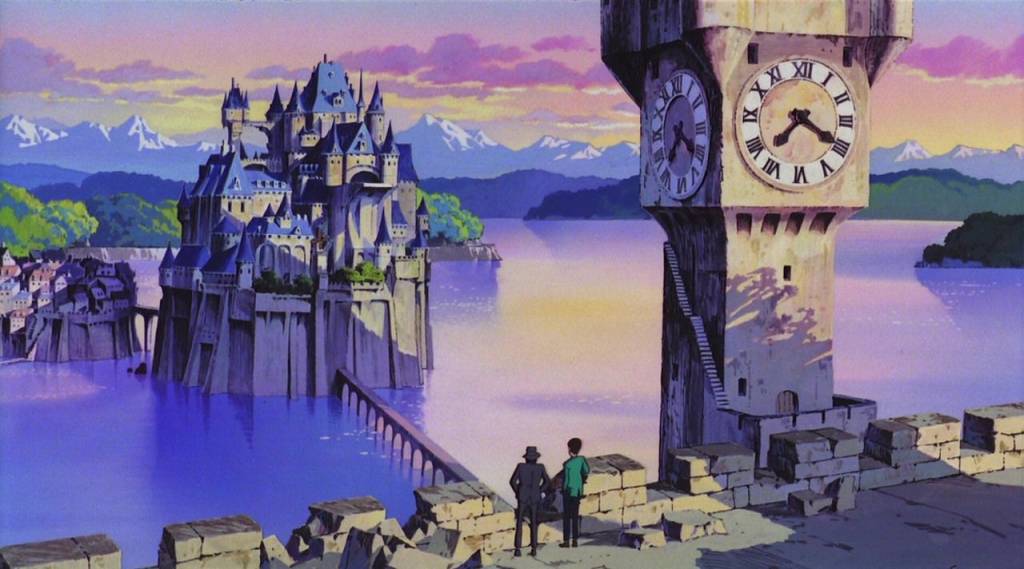

6. Lupin III: The Castle of Cagliostro / Rupan Sansei Kariosutoro no Shiro (1979)

The first official film by Miyazaki marks something that is rarely seen in the back catalogue of great film directors – a true masterpiece debut. The Castle of Cagliostro was not seen widely outside of Japan until the 1990s, and even now, it remains extremely underrated and arguably overshadowed by the continuing gregarious Lupin III anime franchise that it came from. It was made in a time when available technology for animation was still quite crude, and yet what Miyazaki achieves is something so refined and beautiful. Given his experience in the TV and comic book world, Miyazaki knew what he wanted to make and how it was to be presented. Cagliostro stands out somewhat in his filmography, mainly because it is a spy adventure story rather than magical-realism. But it is an absolute hoot. The character of Lupin is a likable rogue (unlike earlier depictions in the TV series), who along with his cohort of friends and enemies frequently chew up the scenery with quick quips and gags. Inspired by landscapes from Europe, but also bringing Miyazaki’s own style and flair, the visuals carry a real punch. The clear attention to detail was ground-breaking for animation at the time.

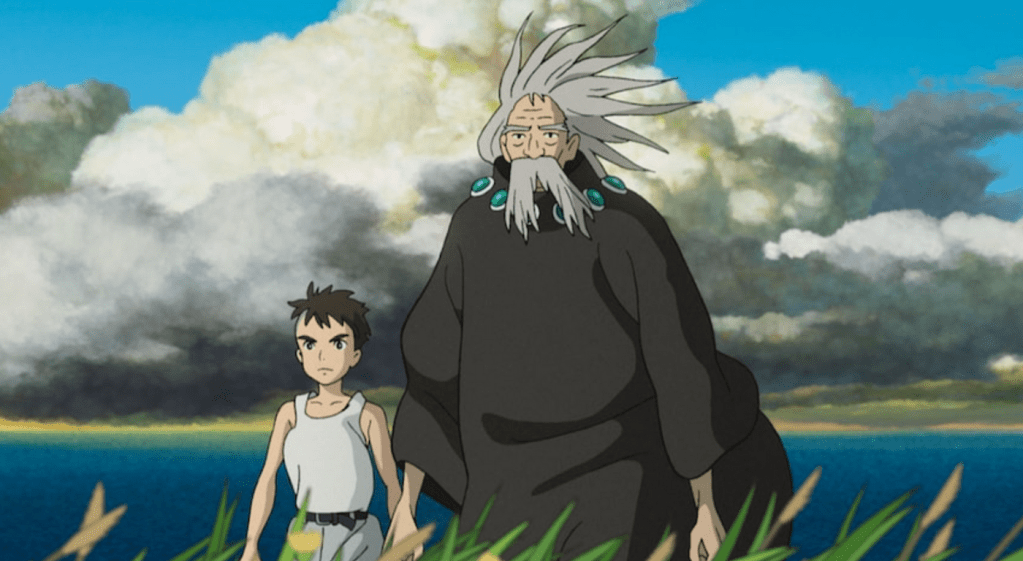

5. The Boy and the Heron / Kimitachi wa Dō Ikiru (2023)

The latest from Miyazaki (a film in the making for seven years) is an unsurprisingly eventful watch. Out of all his films, I don’t think I found myself as profoundly effected as I was with this one, but I guess as a lifelong fan that might have something to do with my expectations. It really felt like his most personal offering yet (and possibly his last?), almost like he was reaching into his mind and soul to genuinely figure out what life is all about. You can see parts of all his previous films, and the usual themes that go with them. Death and mortality take a central role, but in its treatment, Miyazaki is making a strong point about life, or more importantly, about ‘Ikiru’ (living). The central character is a young boy who is struggling to come to terms with his mother’s death from a horrific fire during the Pacific War. He moves to a country house to live with his pregnant aunt (now his step-mother) and is soon compelled by a mysterious tower on the estate grounds – of course, the tower is watched over by a cheeky grey heron that seems to be slowly morphing into a human. It really is incredible stuff. The pace is slow at first and then once we are in that other dimension world of creative dreams (assuming this is Miyazaki’s own head) we are in for a thrilling and enjoyable ride. The film is about relationships, dealing with depression, and making choices in a chaotic world. The lessons for young adults are everywhere, and you cannot but admire Miyazaki’s dedication to making something so meaningful and hopeful…even for someone who has probably seen it all.

4. My Neighbor Totoro / Tonari no Totoro (1988)

As I described here, My Neighbor Totoro is the epitome of escapism – a whimsical embrace of youth, adventure, and imagination. It truly is a beautiful film! There is no surprise that the marketing department at Studio Ghibli saw gold here, given the presence of many cuddly, friendly creatures – Totoro has become the emblem of the studio ever since. But of course, Miyazaki’s mind was not on the money when he created his characters. Like in many of his later films, these creatures are spirits, and like Totoro, they are often friendly to humans. They are enshrined in the Shinto belief of animism, where places and environmental features can manifest as spirits. Miyazaki has always maintained that a child picks up on things differently than adults, and so in My Neighbor Totoro, he utilises this as a device to open up a boundless world of joyous delight. But like in so many of his films, he grounds this delight against a backdrop of something serious – the young protagonists’ mother is sick in hospital with an unspecified illness. It hangs over the film with uncertainty, but because we are wedded to the magical worldview of the sisters Satsuki and Mei, that uncertainty frequently dissipates, whether by Totoro’s slow belly breaths or by the smiling ginger cat-bus! And we can only but revel in it.

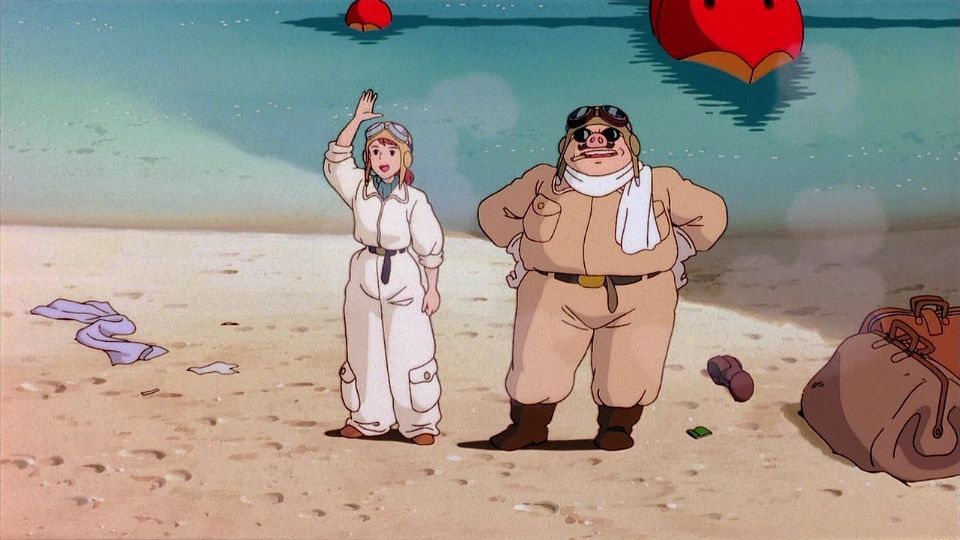

3. Porco Rosso / Kurenai no Buta (1992)

‘Better a pig than a facist’ – this is a line uttered by the film’s literally pig-headed protagonist and gives you a flavour for what’s in store in this wonderful and magical anime. With Porco Rosso, Miyazaki moved things into the adult world a bit more than his previous films, although the prominent secondary character of Fio provides a youthful and feminist flair to the story. Marco/Porco is a daring Italian WWI veteran pilot who now works freelance as a pirate hunter in the skies over the Adriatic Sea. A mysterious hex has caused his head to be transformed into a pig’s head, hence the nickname of the film’s title. Porco is an enigma and a maverick, and as with many of Miyazaki’s heroes, he is generally a pacifist and has a soft heart. Miyazaki includes historical political commentary with his setting around the Italian coast in the 1920s, but for the most part, what dazzles the viewer most is the animation. We see stunningly rendered European landscapes and cityscapes mostly visualised from the skies, and the attention to detail of aircraft from a certain vintage is amazing – this indeed was Miyazaki’s passion project. The energetic flying sequences, stacked with rolling plateaus, terrifying wind, and human emotion, are truly breathless.

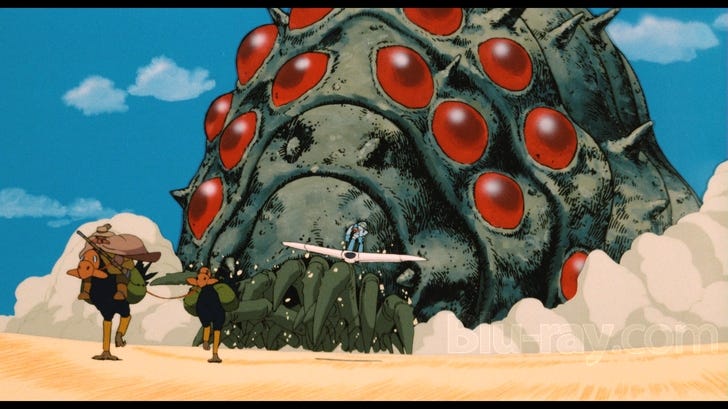

2. Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind / Kaze no Tani no Naushika (1984)

You could say this is Miyazaki’s most fully realised story among all of his projects. He had commenced it as a manga comic book series in 1982, and then received funding to adapt it into a film. The story is set in a post-apocalyptic world and is based around a princess called Nausicaä, who becomes involved in a war that threatens environmental catastrophe and in turn the destruction of humankind. The story is ambitious, but at no point does Miyazaki appear at odds with his own destiny. The film adaptation offers epic proportions and duly delivers. And for an animation made in 1984, it still looks fresh and awe-inspiring. Miyazaki has cited many influences such as The Lord of the Rings and Frank Herbert’s Dune, and you can sense the expansive nature in the universe of Nausicaä. And at its core are tremendously realised characters. The princess Nausicaä is an extraordinary young heroine, fighting on behalf of the environment in a way that transcends usual war story tropes. She is a young role model, and indeed, although it is at times dark and violent (with an unsurprising manga element to it) it is a story for young adults filled with lessons about how to approach and advocate for nature and at the same time, deal with troglodytes who want to destroy it for capital gain.

1. Princess Mononoke / Mononoke-hime (1997)

I have waxed lyrical about Princess Mononoke before. But nothing gives me more pleasure than to watch this film over and over again. It is a neat companion to Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind and Laputa: Castle in the Sky in its treatment of environmental issues. But Miyazaki goes even further here and evolves his gaze towards indigenous peoples’ issues. And in the 1990s, with more funding available, Miyazaki was (reluctantly) able to take animation to new levels with the addition of digital technology. What we get is something astonishingly vivid. The story is arguably Miyazaki’s richest, and most certainly, his most complex. Set in an alternative medieval Feudal Japan, Princess Mononoke presents the epic and sometimes romantic tale of Ashitaka and San and their involvement in the struggle between the spirit world and the mine-hungry humans who are encroaching upon it. The sum of all the film’s parts makes for a true masterpiece of cinema – the characterisations are rich and relatable; the story is entertaining and profound; the themes are relevant to everyone and they are powerfully communicated. Miyazaki’s film is a testament to the human imagination. He offers his take on humanity’s relentless push towards economic progress at the expense of nature and the earth itself, and he doesn’t shy away from offering solutions. This is the masterful technique of Hayao Miyazaki – he can create incredible art, and he can make a powerful statement about our existence while doing so.

One thought on “Hayao Miyazaki’s Movies Ranked”