This is the first in a series of posts on the filmmaking of Alfred Hitchcock (1899-1980), one of the greatest directors of all time. These posts will be authored by Robin Stevens, JJ McDermott and Alan Matthews, and the idea is for each part to take a selection of Hitchcock’s films and analyze them in detail. Hopefully they will present somewhat of a new insight into his films as well as a look into the man himself and the times in which he lived and worked. Robin will begin here by putting a deep focus on three of his most illustrious achievements in cinema: Rebecca (1940), Rear Window (1954) and The Birds (1963). Spanning across three decades, these three films mark momentous peaks in Hitchcock’s filmmaking career, from his first Hollywood production through to arguably his most memorable cinematic achievement and finally, to his last truly successful film.

**********************

I thought this would be easy, but it wasn’t. There are so many reviews and insightful analyses of Hitchcock films out there, and so many themes and techniques covered that I was stumped as to what to say that might be new. A page or two just cannot do justice to any one of these films. In the end, I have gone minimalist, and picked a few underlying themes in each of the films. At the end of the day, my over-riding advice to the reader is this: you should watch these films. They are a hell of a lot more interesting than my reviews.

Rebecca (1940)

(Selznick International Pictures & United Artists)

Featuring Joan Fontaine, Lawrence Olivier, Judith Anderson and George Sanders.

Based on the novel Rebecca by Daphne du Maurier.

Themes: Psychological Assassination, Gothic Horror, Good v Evil

‘Last night I dreamt I went to Manderley again’.

The narrator of this Gothic-like dream-scape is a non-person. We never learn her first name. She lives in the shadows and expectations of others. In many respects, the film is about love and jealousy, and above all about power relationships. Rebecca is Hitchcock’s first American movie, and the only one of his movies to win a Best Picture Academy Award. It is a psychological thriller based on the novel of the same name by Daphne du Maurier. Hitchcock in fact adapted three of du Mauriers’ stories for his films throughout his careers (Jamaica Inn and The Birds being the others), but this is the one that most closely follows her narrative. The set design, photography and lighting are dynamic and impressive here. As always, Hitchcock has an excellent script and a great cast of actors.

A young and worldly-innocent woman (Fontaine) falls for the much older and wealthy, sometimes charming, sometimes brooding widower, Maxim de Winter (Olivier). They marry hurriedly, and after their honeymoon she moves into his grand mansion home, Manderley, on the Cornwall coast in England. But the new Mrs de Winter lives in the shadow of the first Mrs de Winter, the now deceased Rebecca. Rebecca was a popular socialite, throwing lavish parties, wearing fine clothes and altogether more comfortable in a world of wealth, style and elegance. The new and younger Mrs de Winter is anxious that she cannot live up to the expectation of others. From the time she first enters the house, Rebecca – whom we know by her first name – pervades the air. And the young wife feels as if she will always be judged as something less worthy in comparison. Her anxiety is increased by Maxim, who is often remote, unfeeling and incapable of providing the sort of support she needs. He also has a secret that hangs heavy upon his shoulders. On top of this, Manderley’s stone-faced head housekeeper Mrs Danvers (Anderson), who was so close to Rebecca, can barely hide her disappointment and growing contempt for the new Mrs de Winter. She calculatingly sets about to taunt her, and a sort of psychological assassination ensues.

A slightly drab Mrs de Winter (Fontaine) overwhelmed and diminished upon her entry to Manderley

The scene is set in a manor house on a wild and woolly coast. It is grand and majestic, and yet something dark and mysterious is lurking in the shadows. The new Mrs de Winter is portrayed more as an innocent child wanting to find acceptance, trying to live up to the expectations of others without really knowing how. She is vulnerable and presents as easy prey to the manipulative Mrs Danvers, who constantly reminds Fontaine’s character about the all-pervading presence of Rebecca in the house, as if she were part of the architecture itself. She even shows her Rebecca’s personal items, including her hairbrush and her underwear as she stares at them starry eyed in remembrance. Some reviewers see lesbian overtones here. I think that is over-stating it, but du Maurier certainly liked her female characters to be ambiguous. Mrs Danvers tries to organise the new Mrs de Winter into a routine that used to be utilised by Rebecca. Seemingly, this is to suggest how the new wife might be more acceptable to Maxim, but really it is to see her fail and become diminished in the eyes of those who loved Rebecca. For she can never replace Rebecca, and Danvers is on a mission to prove it. She tells the new Mrs de Winter:

Sometimes, when I walk along the corridor, I fancy I hear her just behind me, like a quick light step. I couldn’t mistake it anywhere, not only in this room, but in all the rooms in the house. I can almost hear it now … Sometimes, I wonder if she doesn’t come back here to Manderley, to watch you and Mr de Winter together.

‘I wonder if she doesn’t come back here to Manderley, to watch you and Mr de Winter together’. This picture shows very well the influence of European silent films on Hitchcock, with the face and body language doing the talking, highlighted by dramatic lighting.

In the film, it is the relationship between Mrs Danvers and the new Mrs de Winter where most of the tension resides; a tension between good and evil. It is, in many respects, these two character’s film. Fontaine and Anderson are both remarkable and convincing. When the new Mrs de Winter finally begins to assert her authority, and refuses to play a ‘new’ Rebecca, Mrs Danvers sets out to destroy her completely. This leads to one of the best scenes in the film. Danvers’ words have affected Mrs de Winter self-esteem. She is ever-aware that Maxim is probably still in grief for Rebecca – he is frequently aloof and deep in thought. She looks for affection from him but worries she can never measure up to Rebecca. Hence, Danvers comes to the rescue! At an upcoming costume ball, the new Mrs de Winter should have a stunning gown that will impress all, especially Maxim. Danvers shows her a family portrait and says that the gown worn by a cousin of Maxim in the painting was his favourite. They arrange to have it made and delivered in time for the ball. The new wife has no idea that the gown was actually Rebecca’s. On the evening of the ball the new Mrs de Winter, ecstatic in anticipation, descends the staircase. She cannot wait to see Maxim’s face. He turns and glances up; and his face turns to stone. He shouts, ‘What the devil do you think you’re doing … Go and take it off’. The girl is crushed and bewildered, and she rushes upstairs in humiliation. She realizes that she has been set up by the manipulative Mrs Danvers, who is unrepentant and continues to goad the devastated new wife:

I watched you go down just as I watched her a year ago. Even in the same dress you couldn’t compare … You thought you could be Mrs de Winter. Live in her house. Walk in her steps. Take the things that were hers. But she’s too strong for you. You can’t fight her. No one ever got the better of her. Never. Never.

Collapsing in tears on the bed, the new Mrs de Winter knows she can never match Rebecca in her husband’s affections, or anyone else. Danvers opens the upstairs bedroom window and encourages her to get some fresh air. As Mrs de Winter looks out, Danvers stands behind her, talking over her shoulder:

Why don’t you go? Why don’t you leave Manderley? He doesn’t need you. He’s got his memories. He doesn’t love you – he wants to be alone again with her. You’ve nothing to stay for. You’ve nothing to live for really, have you? Look down there. It’s easy, isn’t it? Why don’t you? Why don’t you? Go on. Go on. Don’t be afraid!

This has got to be one of the all-time great pieces of Gothic cinema. As Mrs de Winter in exhaustion and utter despair ponders her desperate position, the woman behind her encourages her to kill herself. And did you notice: Mrs de Winter is in white; Mrs Danvers is in black. Dark shadow is behind, misty light is outside the window. Mrs de Winter slowly blinks her watery eyes. Danvers stares at her, unblinking, urging her to end it all.

Unlike most of his films, Hitchcock only had partial control over this film. The story stayed faithful to du Maurier’s novel, which was at producer David O. Selznick’s insistence. However, the direction is unmistakably Hitchcock. In many of his films – this one included – the face tells us more than words. Hitchcock always liked close-ups. He learned this from his great love of silent movies and the power of emotion conveyed in German expressionism and other European films of the time, which used elaborate stage settings and exaggerated light and shade contrasts to evoke emotion. He was from the school of thought where a story can be told in imagery. The most remarkable vision of all in Rebecca is the silent Mrs de Winter staring out of the window, surrendering herself to a final fate, and Danvers behind her with an intensity of purpose to make her do it. Great actors, of course, but the stage setting, lighting and sound are all used to great effect here too. The score eases to a steady creeping wave of sound, and the light behind them darkens, creating deeper shadows upon their faces. As they both lean gently forward, Mrs de Winter’s face in mesmerised trauma sinks into complete shadow, and the shadows on Danvers’ face intensify her menacing expression. Indeed, the manor house, with its dark shadows and shafts of light from high angles, is a wonderful device to illuminate or diminish a character.

The scene continues. There is a commotion below the window and Mrs de Winter regains herself. The body of Rebecca has been found in a watery grave. Mrs de Winter meets Maxim at the beach house shortly afterwards. She learns that Maxim had killed Rebecca, but he explains to her that it wasn’t intended. He pushed her as she goaded him, and she fell and hit her head. According to du Maurier’s novel, Maxim killed her in a rage, but this was unacceptable to the American film board at the time – a killer cannot be seen to evade justice – so it is stated he accidentally killed her, but it is implied that perhaps it was more intentional. Hitchcock pushed it as much as he could, short of censorship (In fairness, the script-writers here stayed mostly faithful to the book otherwise). This discussion changes everything. Rebecca is not the golden statue of virtue in the eyes of Maxim, and she sees a way to support him and make a life together without the encumbrance of Rebecca.

There are a few reviews that suggest that we only ever know the ‘real’ Rebecca through Maxim’s hatred of her. But I don’t think that is quite right. Maxim’s friend and neighbour Frank Crawley (Reginald Denny) whom we know to be a kind and thoughtful person, also dislikes Rebecca, knowing firsthand that she had a devious side. Also, Rebecca’s loathsome and deceitful cousin Jack Favell (wonderfully portrayed by George Sanders) as well as the cold and calculating Mrs Danvers, who cherished her, both make it clear to the audience that Maxim’s view of Rebecca’s selfish character is closer to the truth. However, Rebecca the novel is based on du Maurier’s own jealousy towards the towering (spiritual) presence of her husband’s first wife. And she too signed her name with a flourishing ‘R’. Like many of her characters, she paints a leading lady in dynamic opposition – wonderfully good, then reigning evil – from the perspective of another character, only to question at the end of the book whether that was an accurate portrayal or some temporary madness in the man who loved her but could not control her (aka My Cousin Rachel).

The story progresses through to an enquiry into Rebecca’s death and the investigation into Maxim’s knowledge and or complicity in it. Alas, he is cleared of any suspicion. While Maxim and Mrs de Winter are away during this time, Danvers catches wind that Maxim may have killed her cherished Rebecca. In her rage, she sets fire to the mansion. Maxim and Mrs de Winter return home just in time to see Manderley burning to the ground. It is a bit like the two sides of Rebecca, as seen in the eyes of others. It is both glorious and majestic, and dark and foreboding: a symbolic effigy of Rebecca in gothic masonry that finally returns to dust.

**********************

Rear Window (1954)

(Patron Inc. & Paramount Pictures)

Featuring James Stewart, Grace Kelly and Raymond Burr.

Written by John Michael Hayes, based on the story ‘It Had to Be Murder’ by Cornell Woolrich.

Themes: Voyeur or Witness?, Dualities in Cinema

Hitchcock’s Rear Window is one of the greatest suspense movies of all time, and, along with Vertigo, is arguably the best of Hitchcock’s impressive list of films. As always, Hitchcock assembles an excellent cast and has a talented and experienced crew of cinematographers, writers, editors, set designers, lighting and other technicians all making a notable contribution.

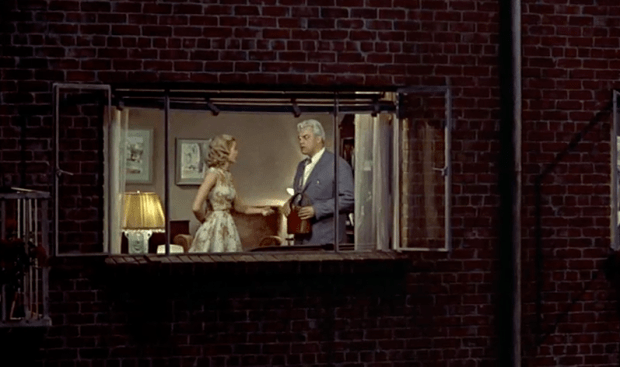

The film follows the perspective of professional photographer, L. B. Jefferies or ‘Jeff’ (played by Stewart), who after breaking his leg is wheelchair-bound and confined to his apartment during a scorching summer. His elegant high-society girlfriend, Lisa Fremont (Grace Kelly) visits him regularly. His rear window is wide open to catch the day-time breeze and the evening cool air. It looks out over a small courtyard and into the rear windows of several other apartments opposite – these are also open in the sweltering heat. He takes to observing his neighbours – a ‘voyeuristic’ enterprise that relieves the innate boredom of being stuck in a wheelchair – and he becomes increasingly intrigued by the goings-on of jewellery salesman Lars Thorwald (Raymond Burr) and his bedridden wife. One night, Jeff hears a woman scream, then a shout ‘don’t!’, accompanied by breaking glass. After observing a series of unusual and suspicious activities by the salesman, and then noting the sudden absence of his wife the next morning, Jeff becomes convinced that Thorwald has murdered her.

The character of Jeff is based on real life war-time photo-journalist Robert Capa, whose career was centred on observing the violent mayhem of a world in conflict through the dispassionate artifice of a camera lens. Capa, by the way, had an affair with Ingrid Bergman while she was working on the earlier Hitchcock film Notorious, and Hitchcock, some believe, made observations of them, which he reproduced in the romantic tension of the relationship between Jeff and Lisa in Rear Window.

Jeff loves his affluent socialite girlfriend (surprise, surprise, a stunning blonde), but cannot commit to a permanent relationship with her. Their worlds are too far apart. He tells her ‘I need a woman who is willing to go anywhere, do anything’, and that it is unfair to put that on her. She deserves better. She reproaches him with a sad pleading ‘You don’t think either one of us could change?’, affirming that she just wants to find a way to be part of his life. This simple scene sets an underlying theme in the film. They both change. In some senses they switch roles, but importantly they become active together.

Jeff (Stewart) ogles at his girlfriend Lisa (Kelly)

After Lisa and visiting day-time nurse Stella (Thelma Ritter) lecture him on his morally questionable and intrusive observing of the lives of others, they too, at his beckoning, become involved. Lisa, keen to be part of Jeff’s world, begins taking risks in a dangerous drama to ‘get to the truth’. He watches through the lens at a distance (like in his job), silent, powerless and alarmed, but also enticed and compelled by what is going on. Like the cinema viewer, he cannot turn away. This ‘dispassionate’ observer is now very invested. In one part of the film their roles are reversed: she is in the thick of it, taking risks, and he is sitting at home, anxious and helpless. There are several tricks that Hitchcock utilises to great effect in this enterprise. Much of the film is photographed from Jeff’s visual perspective. When he looks out of his window, the viewer sees what Jeff sees: the partially open, partially obscured scenes of urban life in his neighbours’ windows, and the distanced and slightly muffled sounds of their affairs. Almost never do we see inside their apartments i.e. from their perspective.

Let me pause here to make a few points. Many reviewers state that the whole film is from Jeff’s visual (voyeuristic) perspective. This is just not true. Large parts of the film are set in his apartment and the camera pans back to capture the view of whoever is speaking or takes a neutral perspective. The camera is pretty much evenly balanced between what Jeff sees outside and what we, the audience, see of Jeff, Lisa, Stella or even the Detective (played by Wendell Corey) inside. In one scene the viewer is offered a ‘window’ into the private life of Lisa and Jeff: she arrives to the apartment with an overnight bag containing one item – a negligée. Hitchcock again and again plays with dualities; such as the individual/collective or impassive/active or outside/inside.

And while I’m all fired up (WARNING – a rant about to begin!!), if you type Rear Window on Google these days, you will find plenty of reviews about the film, a significant number of which refer to Hitchcock’s frequent use of voyeuristic elements on screen – and that the cinema-viewer, too, is enticed into this voyeuristic enterprise. Some books on film craft, too, say this. Sure, there are elements of this in the film. Hitchcock likely used this to promote it, but that is not an accurate characterisation of the film. Even if we reduce the meaning of voyeurism to spying on people with a sort of obsession or intrigue (which is not actually the same thing as voyeurism), that is still not what this film is about. It is a minor selling point for lazy critics and theatre promoters (Many of the same critics say the whole film is from the visual perspective of Jeff. Film critics, you might conclude, apart from me, Alan, JJ and David Stratton of course, are a bunch of lazy $#!*$!).

The film is more about a passive observer being spurred into action by an injustice (the opposite of a voyeur), played through a role-reversal in a romantic relationship. That is its underlying theme – and it seems obvious to me that the main character should be a photo-journalist; that is, a witness to events who then broadcasts it to the world. Right from the very beginning, we know Jeff cannot stand being reduced to staring out of his window in this ‘swamp of boredom’. It is mindless and tedious, but occasionally amusing. His view only changes when the swamp of boredom becomes the place of action. Jeff unwittingly returns to what he knows – journalistic observing through a lens. What he sees prompts him to act, but being stuck in a wheelchair he requires others to help him. This is a journalist photographer perspective, not a voyeur. As stated above, Hitchcock based Jeff on photo-journalist Robert Capa, who photographed some of the most momentous events of his day, perhaps a little like Hitchcock himself, who filmed Nazi atrocities at the end of the World War II. The intent is to move the silent, distanced observer into action. I cannot help but think that this is a comment on how terrible things can go on around us, while we are often oblivious to it. In Rear Window, this is not only about the murder, but it is also shown when Stella is motivated to intervene in Miss Lonelyhearts’ suicide attempt. To fill you in, when we first see Miss Lonelyhearts, we note she is a middle-aged woman, living alone, and night after night she plays out an evening with an imaginary boyfriend or suitor. In the background we can hear Bing Crosby on her gramophone romantically singing ‘I See You’. Sad but poignant. These very human moments in the film elicit empathy, drawing the viewer in more and more as events unfold.

Hitchcock provides guidance to Kelly and Stewart on set

The realism of the film is helped by the wonderful set design by Hal Pieira and Joseph MacMillan Johnston, which is based on a real New York residential courtyard. Though the courtyard is communal, the windows of each apartment are like separate stage sets, where the residents’ lives play out in isolation from their neighbours. I especially love a scene where Jeff is looking through his camera, and we see his intense anticipation and the reflections of all the separate apartments in the camera lens. Beautiful.

The film builds in intensity as Lisa and Stella become increasingly involved. At one of the most pivotal scenes in the film, Lisa has broken into Thorwald’s apartment, when he unexpectedly returns and discovers her. Stella and Jeff look on helpless and in desperate anxiety. Lisa is in the thick of the action, in imminent danger, and he is at home, unable to do anything. Their roles are reversed, and Jeff sees her in a new light. She is now prepared to do anything so as to be part of his world.

As an interesting side point, Hitchcock had held resentment towards producer David O. Selznick’s who had interfered in many of his earlier Hollywood projects, especially Rebecca. With Rear Window, produced by Paramount, Hitchcock took his revenge. The cold, scheming character of Lars Thorwald was purposively made to look like Selznick: same glasses, same stare. In fact, Hitchcock personally coached Raymond Burr, who played the character, to master some of Selznick’s mannerisms.

David O. Selznick

The police enter Thorwald’s apartment just in time to prevent Lisa being hurt. Thorwald realises at this point that Jeff is ‘sussing’ him out. He takes immediate action. Jeff sees the danger, but he is alone in his apartment and so is forced to await this impending menace. Through Jeff’s eyes, the viewer is now witnessing the action. We are no longer the distanced observer. Thorwald enters Jeff’s apartment. Jeff puts up a struggle, temporarily blinding the assailant with camera flashes, but he is no match for the powerful and menacing Thorwald. Thorwald holds him half out the window, and Jeff cries out for help. For the first time the camera suddenly swings outside Jeff’s apartment, looking in his rear window, reversing the perspective to that of his neighbours, who have come to see all the commotion. Police rush in to arrest Thorwald but Jeff falls to the pavement. His fall is broken by other officers below.

Look at the sequence of these shots – Jeff watches Thorwald from afar

Lisa accosts the dangerous Thorwald as Jeff looks on helplessly

The police enter the apartment just in time, as Lisa signals to Jeff

Thorwald, now enraged, turns to look with menace directly at Jeff

As can be seen from the picture above, we become more involved in a rapid turn of events and the lens zooms in. Hitchcock pulls us into it – from distanced observer to invested witness – and suddenly we, the observers, are the hunted. Hitchcock produced one of the most engaging and suspense-filled dramas on film with Rear Window. Because much of what Jeff sees is what we see, we are directly within the action, inside the drama of his character and the events that surround him. It’s one of the great thrills in watching this film.

**********************

The Birds (1963)

(Alfred J. Hitchcock Productions & Universal Pictures)

Featuring Tippi Hedren, Rod Taylor, Jessica Tandy and Veronica Cartwright.

Screenplay by Evan Hunter, based on the story ‘The Birds’ by Daphne du Maurier

Special effects by Ub Iwerks.

Theme: Silent Menace, Animals v Humans, Inexplicable Terror

How does that old Hollywood saying go? ‘Never do a film with animals or children!’ Unless of course you are Alfred Hitchcock and you want the animals to terrorise the kids that is! Starting as a light-hearted and mildly comic romance, The Birds quickly turns into a weekend of terror. The Birds was a technical masterpiece of its day, and for Hitchcock, probably the most difficult movie for him to film. It is loosely based on the 1952 short story by Daphne du Maurier. The horror element is centred on a series of sudden and unexplained violent bird attacks on the people of Bodega Bay, California over the course of a few days.

Melanie Daniels (Hedren), a young socialite, and lawyer Mitch Brenner (Taylor) meet in a San Francisco pet-bird shop, when he goes to buy a pair of lovebirds for his sister Cathy’s (Veronica Cartwright) eleventh birthday. There is a playful interchange between them, and a few days later she heads to his Bodega Bay address to anonymously leave a pair of lovebirds. But he sees her, and sparks are ignited. At his request, she stays for the evening, and ends up renting a room from Mitch’s ex-girlfriend Annie Hayworth (Suzanne Pleshette – who, by the way, has jet-black hair, and during film rehearsals she would don a blonde wig and comically play the ‘heroine’, much to the enjoyment of the other actors). There’s a beautiful shot of Annie in the foreground and Melanie in the background. One of Hitchcock’s classic close-ups where faces tell more than words, as Annie sees her prospects with Mitch ever-fading. I think Hitchcock – apart form ‘suspense’ and style – had a great capacity to draw out tension between people on screen, both overt and subtle. In so many of his films, scenes with two people slightly at odds with each other or in playful mirth, are like painted portraits, and a lot of emphasis is placed on showing ‘thoughtful’ eyes – the windows to the soul.

Annie (Pleshette) mulls over Melanie’s (Hedren) phone conversation

Soon after her arrival,a seagull inexplicitly swoops and scratches Melanie. Over the next couple of days birds begin to amass, and without any clear cause, attack the townspeople of Bodega Bay, often with deadly consequences. I know this sounds silly, but apart from the horror, and the techniques used in this film, I kind of liked seeing the leading blonde spend much of the movie with her hair in disarray!!

One of the most visually spectacular scenes – and for its time, quite shocking – is when school children run en masse in terror as hundreds of birds attack them. Like most of the bird attack scenes in the film, Hitchcock used cutting edge technology by adopting the ‘sodium traveling matte process’, which combines separately filmed foregrounds and backgrounds through an optical printer in post-production. It looked remarkably realistic for its time, and still holds up pretty well to this day, although digital mapping of the last ten years or so has finally elapsed it. Technicians had spent months filming birds at San Francisco dumps that could be used in the process. Special bird trainers taught birds to fly straight at the camera or at someone’s hand by placing meat just behind the camera or under their shirt sleeves.

Run!!

This scene of the children running is worth a little more discussion. It combines multiple methods that are characteristically Hitchcockian. The ‘Master of Suspense’ (let’s be honest that term doesn’t come near to characterising what Hitchcock gave to cinema in terms of style and technique) introduces the idea of horror in increments, before overwhelming the viewer in sound and visual effects, so there is no escape. He builds a storm. There is one attack by one bird, then several small birds destroy an outside birthday party, and an even larger mass of birds fly down a chimney into the lounge causing mayhem. A neighbour’s corpse is found by Lydia (Mitch’s jealous mother – wonderfully played by Jessica Tandy) in his house with his eyes pecked out. In rapid succession, we see his legs, his whole body, then his mutilated eyeless face, like our eyes seeing the unfolding horror with every blink. We know then that birds can get inside and they appear to be determined to hurt and kill people – the horror gets increasingly worse with every attack, but before each onslaught, a quiet calm and seeming normality – like the quiet before a devastating hurricane. It is eerie. So what happens next?

Melanie goes to check on young Cathy at school. It is quiet and everything seems normal. Tension. She sits on a bench, a children’s climbing frame behind her. A single crow silently perches on the frame. She takes a puff of a cigarette, and we now see four perched birds on the frame. Another puff, then there are a dozen or more birds. The camera zooms in, and for 30 seconds it holds on her face. It is almost unbearable for the viewer. As she finishes her cigarette she looks up to see one bird flying and then turns around to see the climbing frame completely covered in birds. Although they do not attack her, there is a feeling of eerie menace abound. Melanie goes inside to ask Annie to organise the kids to quietly walk out of the school towards town. All of a sudden the birds take to the sky. The children are out in the open, hundreds of metres from safety. During this scene, Hitchcock moves into rapid-shots and multiple angles to replicate the chaos and mayhem of the attack.

Melanie (Hedren) comforts a terrified Cathy (Cartwright) as Mitch (Taylor) drives them to safety

Cartwright, playing the young Cathy, looks suitably horror-struck throughout the film. You might recognise her in her adult roles: horror-struck at the end of the 1978 remake of Invasion of The Body Snatchers, horror-struck throughout Alien; anxious and terrorised in The Witches of Eastwick. She does horror-struck well and often plays the emotions of the audience member. Hitchcock was conscious always about pulling the audience in and finding characters and scenarios that the audience could easily hook onto. A good example is the scene at the Tides Restaurant after the attack on the school children. We are all thinking ‘well this is horrible, but what’s causing it? Birds don’t just attack people. Is the film going to explain the reason?’ So Hitchcock sets up a whole scene where it is all discussed. There is no clear answer, just people espousing opinions! But that’s okay, we just needed to think that through a bit. And then the horror starts again. In some having it unanswered is better. There’s no solution to the inexplicable; it can’t be contained or controlled.

A gull hits the restaurant window, and the attack on Bodega Bay gas station begins. A bird hits a petrol-pump assistant, he falls and fuel streams across the road to a man about to light a cigarette. People inside the restaurant can see the danger about to unfold. They are calling out, but he drops the match and explodes into flames. Hitchcock uses an interesting montage where each shot of the horrified onlookers (Melanie in mid-frame) is slightly shorter than the previous one. Melanie’s face freezes in three looks of shock and dread, as the people next to her move. It is a strange shot of movement and stasis, but the eyes fixate on Melanie – the look of shock frozen in time – as chaos goes on around her. It is very effective.

The birds-eye view of this attack was filmed by Harold Michelson from a mountain top. The artist Albert Whitlock then painted in the rest of the town on to the actual film negatives. It was then put back into the camera. They filmed birds, and others were painted in so that they were in front and behind various buildings. It was extraordinarily delicate work, and just part of the intricate technical production that went into the overall making of The Birds.

After this attack, Melanie and the Brenners are back home, barricading their home for an expected next wave of attacks. And then they wait. The sounds of birds outside begins, and the people inside shift uncomfortably. As the attack increases, so does the terror. Hitchcock wanted all the actors to react in sync with the escalating attack. Of course, the bird sounds would be added later, so Hitchcock had a drummer off-stage increasing the rate and volume of the beats until it was almost deafening. The actors took their cue from that. It is worth mentioning here that Hitchcock did not want a musical score for the film. He engaged composer Bernard Hermann (Citizen Kane, Psycho, North by Northwest) to work on a ‘score’ constructed from overdubbing bird calls and electric-synthesised bird noises. A remarkable innovation in cinema, that still holds up well to any modern soundtrack. It is immensely effective and adds an extraordinary element of menace to a scene.

The final scene in the film is where Mitch, Melanie, Cathy and Lydia drive out of Bodega Bay in twilight, surrounded by thousands of perched birds. It is apocalyptic. This scene required 36 over-dub exposures; adding birds and a painted landscape. It is a remarkable scene, and ends with an uncertain resolution.

The final scene…Undeniably creepy, right?!

The Birds is perhaps Hitchcock’s last great movie. It starts very lightly with a slight comic and romantic feel to it. As is his trademark, Hitchcock appears in an early scene. There are also a few in-jokes, such as a take-off of a television commercial that starred Tippi Hedren before she appeared in films – the scene where she looks around before walking into the San Francisco bird shop. And then… it creeps towards unease, and eventually floods us with tension and horror. In nearly every film he had done up until then, the tension, horror or suspense was between people, but here, it is the inexplicable actions of animals (the birds…and lots of them) that offers the horror – a horror that cannot easily be resolved. And it isn’t.

**********************

In summary, these are three great films from three different decades, each with a different subject matter, and each with a distinct style. Yet they are unmistakably Hitchcockian. Hitchcock plays with his audience, a little shock, a little humour, a little sad, but laced with an underlying mystery or darkness. He builds tension, eases it, and then builds it again. But in the end, I don’t really know what it is that I like so much about his films. I guess it’s the whole package – great script, carefully selected actors, brilliant editors and lighting technicians, musical scores and cutting-edge film craft. They are works of art. I end as I began: watch the films – they are more interesting than any review or critique I have read. And stay tuned for the forthcoming Hitchcock blogs by Alan and JJ. They will have insights and approaches that are different to mine.

4 thoughts on “Exploring Hitchcock Part 1: A Deeper Look at Rebecca, Rear Window and The Birds”