In his latest book Cinema Speculation, his first non-fiction work, Quentin Tarantino discusses a number of movies he saw in the late sixties, throughout the seventies and into the early eighties. He delves into the era of New Hollywood and delivers a comprehensive and entertaining commentary on films that had the most effect on him during his pre-teen and teen years, and by way of that, offers interesting insights into his own, often troubling, psyche. We all know that Tarantino is a movie-nut, and his own films are notable for their by-the-second b-grade, exploitation cinema references. Cinema Speculation opens a door into how all of this came to be – a LA-based childhood with a single mother, who allowed him to go to the cinema whenever he wanted, sometimes accompanied by her, sometimes accompanied by friends or partners of hers. No doubt a less-than-ideal upbringing is hinted at, but Tarantino, or ‘Little Q’ as he sometimes refers to himself, quickly developed a passion for going to movies, and his unequivocal, enduring love for cinema rings true throughout the book.

But the book also outlines things that perhaps Tarantino never intended for, and I am speaking here about the problematic part of Hollywood – the violent, sexist, misogynistic drive that marked the industry at the time, and later enveloped into the exploitative movie culture of the eighties and nineties, when Tarantino himself entered the fray and continued the trend (arguably making it worse on the violent and misogynistic front). The one thing that draws me to Tarantino, and this book, is that he is never apologetic about who he is or what he thinks. I don’t think he is a terrible guy, but I don’t really know him (maybe tomorrow some horrible revelation may come out that completely changes my mind). I think if I sat down with him to talk about movies, I would enjoy that immensely. His knowledge is second-to-none, and he does harbour empathy about the human experience, so he is not all about the violent and aggressive male energy that often billows from his movies unfettered. I can agree with him on many things, but not everything, and here, over two parts, I break down his thoughts on twelve movies from the book and offer my own thoughts by way of response.

WARNING: Please be aware that the plots of these films are discussed in detail below, and the endings may also be revealed.

***************************

Bullitt (1968, Peter Yates)

What Tarantino Says:

Although he was only six at the time, ‘Little Q’ remembers Bullitt clearly when it came out. He loved how cool Steve McQueen was (his clothes, his haircut, his sexy girlfriend, and the Ford Mustang GT he drives) and how exhilarating the car chase across the streets of San Francisco was. He notes that the film may well be dated by now, and it does not hold the same zeitgeist position it enjoyed during the last decades of the 20th Century. He laments that Gen Z would not enjoy it in the same way he does because their idea of ‘cool’ would not be evident here.

Whereas Bullitt has a story, Tarantino states that it is not a memorable story. But it breaks away from the many generic cop films of the time, because it has integrity and atmosphere. We don’t know anything about Frank Bullitt, but we don’t need to because it is irrelevant. The location and placing of scenes are more important, as too is Lalo Schifrin’s jazz score. Steve McQueen decidedly says very little and creates a memorable character. He is the reason why the film works – rarely has a movie star done so less and accomplished so much. As Tarantino claims, Bullitt is pure cinema.

What I Say:

As I recently proclaimed in my post of favourite movies from the 1960s, Bullitt is a magnificent and utterly unique crime drama. I agree with Tarantino that it is pure cinema. McQueen’s bristling charisma makes every moment watchable. But I would argue that it is not just about Bullitt’s looks and the things he has. It is the fact that we don’t really know what’s happening. I also think that there is a good story to Bullitt if you delve deep enough. I feel like I want to be in that world, trying to figure out the crime with Bullitt, driving around in the passenger seat of his Mustang, trying to understand Robert Vaughn’s smarmy intentions.

The setting in a late-sixties, inner-city San Francisco provides us with a very special sense of place. Everything is presented by cinematographer, William A. Fraker, with a casual, raw energy, and there is no over-elaborate technique on show, and yet we feel a pulsating thrill. There is suspense where there should be no suspense. It is a movie that appears to have been carefully crafted, and yet it comes across as being so effortless in its execution. When I think of what ‘cool’ means, I think of this film.

*************************

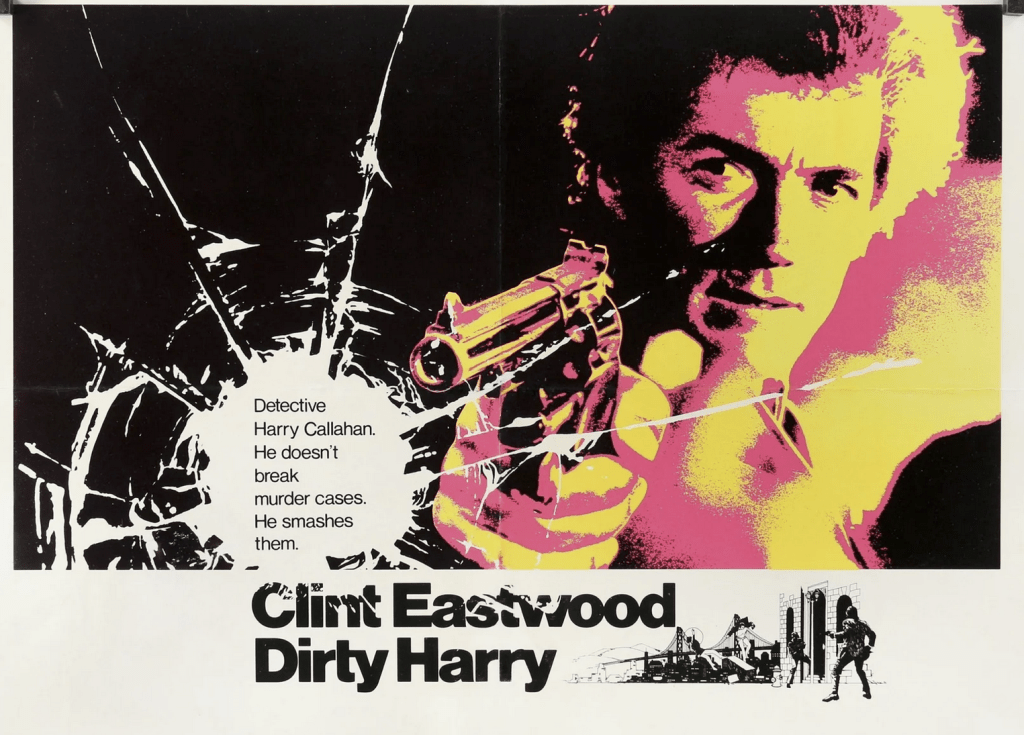

Dirty Harry (1971, Don Siegel)

What Tarantino Says:

Tarantino offers us a surprisingly reflective musing on Siegel’s seminal ‘tough cop’ film of the early seventies. Clearly, the violence of Dirty Harry is reflected in his own films, but here Tarantino discusses the nature of this violence and examines its positioning in the American zeitgeist of the time. He states that Siegel skilfully tailored his film for ‘frustrated Americans who didn’t recognise their country anymore’ – i.e., post-counterculture and during the rise of Black power. He also noted that critics at the time said that the film harboured a racist and fascist ideology. He himself argues that it is not racist or fascist, but is aggressively reactionary against a society that was changing. He also laments that the critics never addressed the obvious quality on show because they were too busy being reactionary themselves.

Tarantino hails Andy Robinson’s bravura performance as the sadistic serial killer, Scorpio, and praises the flair and thinly veiled humour that Eastwood brings to Inspector Harry Callahan. The film, he argues, is more about brutality than bloodshed, and this is why it ages so well. The world in which Harry inhabits is nightmarish, where no one is safe from the depraved monsters of society. But he is thwarted by politically correctness, and he must break this down in order to eradicate Scorpio. Siegel’s film offers multiple justifications for his actions, and the viewer is always on his side. Tarantino figures that Siegel’s creation of plausibility in this scenario is worthy of the highest praise.

What I Say:

I agree that Dirty Harry has an undeniable quality to it, which is mainly down to Clint Eastwood’s fully-formed personification of the lead character, but I don’t think the movie has aged well at all. Having watched it again recently, I did not find it to be the polished cinematic spectacle that people like Tarantino hold it up to be. It has some great scenes, but it also has some corny and poorly realised scenes also. And I say that, even before I get into the fascism and racism.

I think Siegel purposely does not drill down into Scorpio’s motivations, and instead, the devices used to make him appear depraved are deeply contrived – we only see the cold execution and aftermath of his murders. The corruption of the cops and the authorities is also never explored, just a shallow indication that they are incompetent. There are no nuances, only a reactionary feeling that sets us up to gleefully get in behind Clint Eastwood’s .44 Magnum. Because of this, I could not help but feel that Harry is acting with all-out fascistic motivations – even Tarantino himself admits that Harry’s torture of Scorpio in one scene is blatantly fascist. And the beginning of the film, where the bank robbers are all African American (Tarantino explains that ‘militant black revolutionaries’ would often rob banks to buy weapons at the time), also cries out that Siegal’s film is set firmly with a racist attitude. There are no other African American characters to provide a counter-argument. Dirty Harry may be a product of the times, but I think it is ignorant to dismiss its significant flaws nowadays. No matter what Siegel had said (‘I don’t make political movies’), it is clearly a celebration of a fascist cop, and the script undeniably had racist undertones.

*************************

Deliverance (1972, John Boorman)

What Tarantino Says:

Tarantino’s analysis of Deliverance the film is evidently enhanced by his knowledge of Deliverance the novel by James Dickey. The novel, he says, is more expansive on a number of elements that appear in the film (including a homoerotic courtship between the two main characters), and whereas the latter half of the film is defined by the middle-section rape, the latter half of the novel hones in on the characters’ stories, which he prefers. His praise of the film centres mainly on Burt Reynolds’ performance as Lewis and his expert characterisation of a forthright masculine egoist (Tarantino describes him as a poet). He exclaims that his side-lining in the final third, due to an arrow through the leg, contributes to the downfall of the film. The first half of the film, and the rape sequence, however, are excellently handled by director John Boorman.

Given his experience of watching it when it was released, he opines that the film was so effective because the audience had no idea where it was going. It was treated as a wilderness adventure movie, and it had a momentum towards something sinister. But nobody expected the brutal rape that befalls Ned Beatty’s character, Bobby. He describes it as a ‘mindfuck,’ a sort of ancient ritual as shown in a nature documentary, and he comments on the fact that there is no suspense leading up to the scene. He puts its effectiveness mainly down to Bill McKinney, who plays the hillbilly rapist, someone he was genuinely scared of when he first saw the film as a young kid. Deliverance, he says, made people fear the woods just like Jaws made people fear the water.

What I Say:

I don’t currently have the benefit of comparing the novel to the film, but there is something about Deliverance as a story that makes for repeatable viewing. Boorman manages the film so expertly, and I think he adjusts the tone through the oft-discussed middle section perfectly. Even as you watch it now, and know that the rape of Bobby is coming, it is always unexpected. I also think the iconic ‘Dueling Banjos’ scene and the sight of Billy Redden as the boy on the veranda is an effective moment full of menace and the bizarre. Sadly, Tarantino does not divulge much of his thoughts on it, because he is too busy focusing on how great Reynolds and his character is!

Reynolds is definitely compelling, but I think his character is an asshole because all he is interested in is himself and the bullying of others, and to be honest when he gets his comeuppance, it is hard to feel sorry for him. Jon Voight as Ed is not very likeable either. In fact, the four men are not the greatest bunch you have ever come across, but that is likely deliberate on Boorman’s part. The rape scene is hideous and very hard to watch. I would not take the same glee as Tarantino does in describing it. It does not necessarily overshadow the second half of the film, but I do agree that the final third of the film flags a little, and could have fared better if the relationship between Lewis and Ed went somewhere, but indeed that is a modern-day view. I really liked the setting and sense of place offered by the film – Boorman, a British man, gave us a realistically scary view of backwoods America that was never really shown before, and that is its most lasting impression from the film

*************************

The Getaway (1972, Sam Peckinpah)

What Tarantino Says:

As with Deliverance, Tarantino spends a lot of time discussing how The Getaway could have turned out if it had been truer to its source material: a 1950s crime novel by Jim Thompson. He particularly focuses on the surreal ending of the novel, where Doc and Carol find their way to the Mexican ‘getaway’ El Rey, only to find a village full of cannibals. Well, of course he would! Apparently, this bizarre, dark conclusion was jettisoned by Peckinpah because he was intent on making his first ‘hit’ movie, which would have a happy ending. Tarantino doesn’t necessarily think the absence of this ending in the film is such a bad thing, but he does seem to prefer the vicious tone of Thompson’s book. As he laments, Steve McQueen’s Doc McCoy is not a vicious stone-cold killer but, in the book, he is meant to be. But he also notes that Peckinpah’s film plays more like a love story than a crime thriller, and as a result, it is a pretty decent film despite its many flaws.

Tarantino also writes at length about the background of the real-life affair that occurred between stars McQueen and Ali MacGraw during the filming. His thoughts are that you can believe they both fell in love with each other, because emanates from the screen – Doc and Carol are a metaphorical love story for McQueen and MacGraw. He also opines that the decision to cast MacGraw as Carol was key to the movie’s success (there were many other actresses considered). MacGraw’s performance was derided upon release and described as lousy, but over time Tarantino has appreciated her role more because of what she was going through at the time.

What I Say:

Having watched it recently for the first time, I saw lots to like in The Getaway. It is a good movie, but not a great one. I have not read the novel, and I think the surreal ending would be very out of place if it was added to the film. I agree with Tarantino in his assessment of what he believes are the movie’s flaws, e.g., Rudy, who pursues Doc and Carol, and the relationship he has with his kidnapped victim, Fran, is weird and repulsive. But then again, having watched many of Peckinpah’s films, this type of misogynism is not a surprise. Women are treated horribly in almost all his films. Tarantino, who is no stranger to misogynistic portrayals of women himself, has the temerity to explain away Peckinpah’s ‘tough’ treatment as being a reality of the industry he worked in. Even though The Getaway is not as bad as say Straw Dogs or Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia in this regard, I still feel like that the toxic masculinity overwhelms the picture at times. But still, McQueen and MacGraw, and their believable tender moments, play a crucial role in tempering that. I agree that the background to MacGraw’s situation at the time elevates her performance, and Carol is someone to empathise with as a result.

*************************

The Outfit (1973, John Flynn)

What Tarantino Says:

Tarantino makes it clear that John Flynn, an often-forgotten filmmaker of the New Hollywood era, is one of his favourite directors, mainly because his films offered complex male protagonists that end up in a violent catharsis (he also explains that Pedro Almodóvar’s Matador made him believe that films could make violence sexy!) One example was Robert Duvall’s Macklin in The Outfit, based on the character Parker from Richard Stark’s novels. Duvall, he says, gives a masterful performance, and Joe Don Baker as his ‘buddy’ accomplice, Cody, is equally effective. Their affection for one another is a great aspect to the film, and a scene towards the end of the film where Macklin consoles a wounded Cody marks the ‘epitome of poignant masculinity.’ In fact, the final shootout, where they do an all-out assault on the chief villain (played brilliantly by veteran Robert Ryan), is one of the most satisfying climactic shootouts he has ever seen. He also claims that the supporting cast of seasoned B-movie character actors are all perfectly adjudged.

What I Say:

Well, firstly I don’t think violence is sexy. Making it sexy on film is a product of people like Tarantino and his predecessors who have made a career out of trying so hard to make it so. The violence in The Outfit is not at all sexy. It is ugly and repellent, just like its amateur production values. Notably, the film contains a lot of outright violent aggression towards women, and in my opinion, this spoils the whole thing (I think there are some merits). Macklin physically and emotionally assaults his girlfriend, Bett (played earnestly by Karen Black), mainly because she stands up for herself. And then she is shot dead in the crossfire, and we have no other option but to follow Macklin and his buddy Cody as they shoot their way to their apparent ‘catharsis,’ never showing any sign of grief or despair for Bett’s death. The ‘poignant masculinity’ that Tarantino describes is completely lost on me. Maybe if the two characters had a homosexual awakening, the scene (and the ending) would have been more effective, but this is certainly not evident nor would it have been a determination of John Flynn in any case! It is just another example of toxic masculinity in my opinion.

*************************

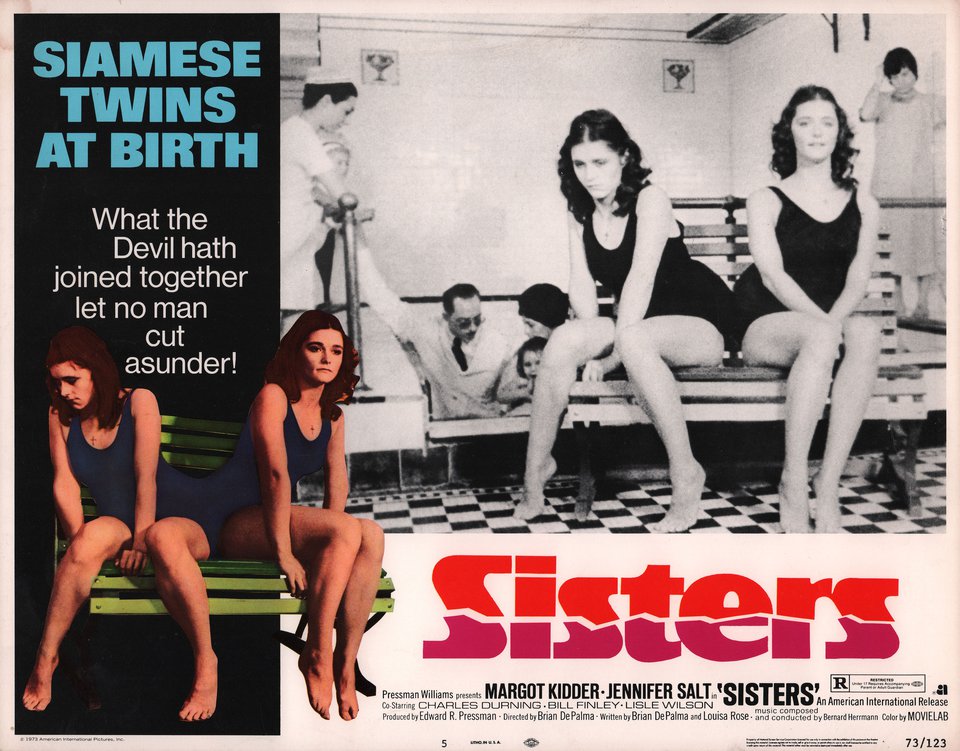

Sisters (1973, Brian De Palma)

What Tarantino Says:

It seems Tarantino has mixed feelings about Sisters. Whereas, he waxes lyrical about De Palma as a director, he finds that the film has not aged well. But at the time it was released, it was very impressive – it was a classy horror film rather than a cheap and generic one. He explains it was a Hitchcock homage and a meta-Psycho reworking, where De Palma employed a manipulative shooting style with techniques such as voyeurism and suspense. Sisters showcases a Bernard Herrmann score, split screens, media-inside-media moments, insane asylums, split personality killers, and all of these were very impressive to a young Tarantino. The script on the other hand is lousy. He feels the film is conformed more by structure than it is by a story, and this is where the film falls down.

Audiences in 1973 were well aware from the beginning that the big reveal was that the two sisters were the same person. Its status as a Psycho rip-off was hard to shrug off. But Tarantino does find that the subversion of a black male victim / white female murderer was a rather progressive stroke for the time. And he also found the witty media satire to be quite enjoyable, e.g., the prize given to the African American actor on the TV show is for a free dinner at a weird and clearly racist ‘African Room’ restaurant. He also describes the birthday cake butcher knife murder to be one of De Palma’s most accomplished sequences.

What I Say:

Sisters is certainly a dated film, but I think it does have some good elements like Tarantino says. The split screen technique looks kind of corny now, but I do get how this could have been effective in creating suspense at the time, given that it was new to mainstream audiences. I have always been impressed by De Palma’s visual style, but I wouldn’t describe his humour as massively effective. I think he failed to reach Hitchcock’s range and level of wit, possibly because he doesn’t possess that trans-Atlantic perspective, and Hitchcock never partook in all-out horror like De Palma does. I would argue that De Palma’s unapologetic insistence to bring violent, sadistic horror themes into the mainstream thriller was his major weakness.

Sisters does appear to lose its way in the second half, and you do start to ask yourself ‘when is this film going to end?’ The suspense becomes a chore, and you don’t really care about the ‘sisters’ anymore, particularly, as Tarantino says, because the gig is up a long time ago. I do think that he is unfair on Jennifer Salt though – he says that she gives a poor performance as the ‘blithering idiot’ reporter. But surely, the weak female character that De Palma created is the problem, not Salt’s? It seems to me that the annoying liberal-leaning, female reporter may have been a personal bugbear of De Palma’s, which is interesting because he was in a relationship with Salt at the time! I think Salt, as well as Margot Kidder as the eponymous ‘sisters,’ are actually quite good.

*************************

Part 2 (Taxi Driver, Rolling Thunder, Paradise Alley, Escape from Alcatraz, Hardcore and The Funhouse) to follow….