Running around banging your drum like it’s 1973

‘This is the Sea’ by The Waterboys

At the risk of raising the ire of those of you born around or before 1973, I do need to point out for the purposes of this post that it was 50 years ago! But on the plus side, I am trying to argue that this was indeed a great year for cinema, perhaps even the greatest year. In the US, innovative young filmmakers were starting to reach the peak of their powers in the so-called New Hollywood era. The producer-driven system was waning as audiences sought out the exciting new delights of thrillers and dramas being offered by the likes of Francis Ford Coppola, William Friedkin, Peter Fonda, John Schlesinger, Peter Bogdanovich and Robert Altman. 1973, the year the Vietnam War ended, saw acclaimed features for the first time from the likes of Martin Scorsese, George Lucas, John Milius and Terrence Malick, while Steven Spielberg was working on his theatrical debut The Sugarland Express. This was a period that showcased the pinnacle of creative output from some of the greatest minds ever to delve into movie-making. It has had a lasting impression on the film industry, and names like Lucas, Spielberg, Scorsese and Coppola are easily recognised by young audiences even today.

It is also notable that this timely invigoration of Hollywood had a big impact on the old as much as the new – Sam Peckinpah was pushing the revisionist Western fad with a mix of old school violence and new age cool (Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid had music and a starring role from Bob Dylan), while John Huston, ever the storyteller, utilised ‘Cool Hand Luke’ himself, Paul Newman, for a retro spy film called The Mackintosh Man. Out in the world, Herzog, Fassbinder and Wenders were spearheading the New German Cinema movement, the marvellous François Truffaut continued to experiment with cinematic techniques long after the French Nouvelle Vague left its mark, Paul Verhoeven was emerging from the Netherlands as a major talent, Alejandro Jodorowsky was creating crazy stuff in Mexico, and art-movie veterans such as Federico Fellini and Ingrid Bergman were making European masterpiece after masterpiece. Even John Wayne was still spearheading Westerns, and in 1973, he starred in two middle-of-the-road movies: The Train Robbers and Cahill U.S. Marshall. This probably aligns with the fact that his ol’ mate John Ford (who died later that year) received a Lifetime Achievement Award from the American Film Institute, presented by none other than Watergate himself, President Richard Nixon.

When I looked into this, I realised that there was a belter being released almost every month that year, sometimes even two, three or four belters. So, I have decided to break down the best films of 1973 on a month-by-month basis (although some months are excluded):

************************************

January

Late in December 1972, Werner Herzog released Aguirre, the Wrath of God in his home country of West Germany, and throughout 1973 it was released in other European countries. It was not released in the US until 1977, where by then it had earned a much-mythologised reputation, much of which is still invoked to this day thanks to Herzog’s own documentary My Best Fiend, which explores his tempestuous relationship with the film’s unhinged lead, Klaus Kinski. The US tagline was ‘On this river, God never finished his creation,’ which certainly sums up the haunting vibe of this un-replicated, untouchable Amazon-based historical epic.

Other notable films released in January were the tough British cop drama by Sidney Lumet and starring Sean Connery, The Offence, and Ingrid Bergman’s Cries and Whispers.

************************************

February

Although it had already become a sensation in its home country of Jamaica, The Harder They Come found a worldwide audience after February 1973, when Roger Corman’s New Line Pictures started to distribute it. This was mainly down to the lead star, Jimmy Cliff, and his sublime music that was used as the film’s soundtrack. Indeed, the film is often cited as the moment that reggae became popularised around the world. Whereas the songs are fantastic, the film itself, although rough around the edges, is also worthy of praise. Perry Henzell directs a vivid story about life in crime-ridden Kingston and he holds no punches.

The same can be said of Turkish Delight from the Netherlands, which is a film directed by future Hollywood psycho-sexual thriller expert Paul Verhoeven. Even then, he was a master of provocation. Introducing Rutger Hauer for the first time, the film explores the relationship of a lazy sculptor and a woman he picks up on the side of the road. Although not the most pleasant of viewing experiences, particularly as it is an early showcase for Verhoeven’s penchant for casual misogyny, it is an intriguing film that sets itself in a specific and unique place (this being Amsterdam in the early 70s) and it does have an unescapable spirited flair that impresses.

************************************

March

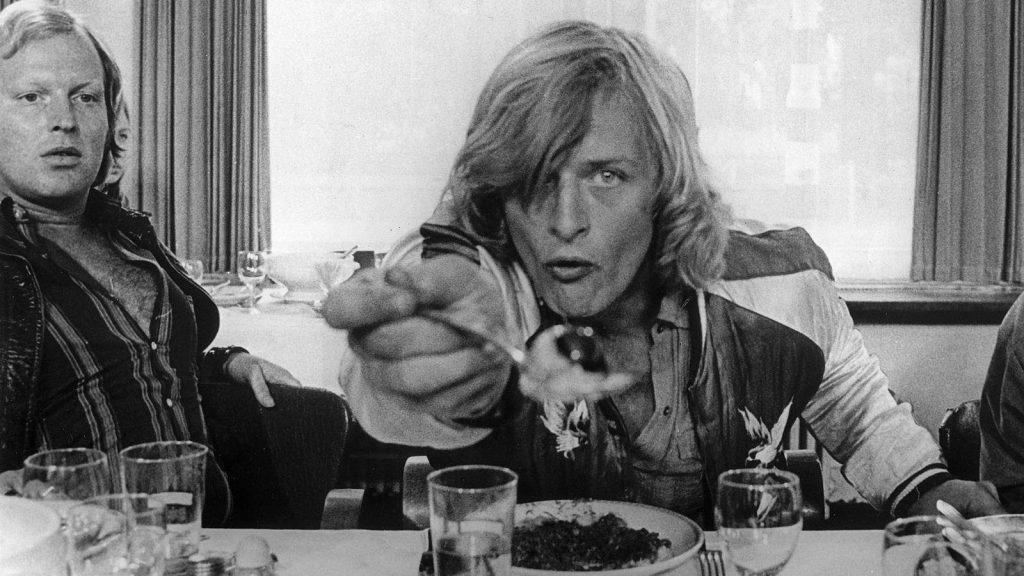

The early seventies were an extraordinary time for Robert Altman. He made M*A*S*H in 1970, McCabe & Mrs Miller in 1971, Images in 1972, and then The Long Goodbye in 1973. Thieves Like Us and Nashville were to follow in the next two years. Notwithstanding the nod to success this clearly implies, Altman endured some serious shit from critics and studio interference during that time, and none more so evident than with The Long Goodbye when it was released in March 1973. Having been marketed as a fun, detective story with Raymond Chandler’s Philip Marlowe as the central character, the initial reception to screenings was frosty and the film had to be pulled and re-released at a later date with a different marketing strategy. The film is now seen as the celebratory initiation of neo-noir – a modern update on the 40s and 50s noir dramas. Altman takes a cool-hand to proceedings and allows lead Elliot Gould free-rein as a confused, nonchalant persona for Marlowe as well as a never-ending supply of cigarettes. Veteran Sterling Hayden appears in an unforgettable role as an out-of-his-mind novelist, whom Gould is investigating. It doesn’t get much better than this, and once you’ve seen Altman at his height, you know exactly where Paul Thomas Anderson’s main inspiration comes from.

************************************

May

It seems like many filmmakers of today have an unhealthy notion about themselves and the work they do, e.g. Damien Chazelle. But movies about movies (or even making a movie about making a movie) has been going on for a while now, and although it does seem very pretentious and self-aggrandising, there are some movies that are worth waxing lyrical over. Vincente Minnelli’s The Bad and the Beautiful from 1952 is one, and François Truffaut’s Day for Night from 1973 is another. It is amusing to note that Jean-Luc Godard reportedly claimed Truffaut’s film was a lie. After watching the film, it seems obvious to me that the intention was not to make you believe that this is what happens behind-the-scenes. Truffaut is rather orchestrating a celebration of filmmaking, an amusing study about the things that could and sometimes do occur on- and off-set. It is very much a comedy and with that, a feel-good entertaining experience that offers love stories, tragedies, glamour, petulance, arrogance and at its heart, a homage to the greats of Hollywood’s past….but in French of course.

Other notable films released in May were Paper Moon by Peter Bogdanovich (Ryan O’Neal RIP), The Day of the Jackal by Fred Zinneman, the afore-mentioned Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid by Sam Peckinpah, and the unfortunately-titled, but well-received The Mother and The Whore by Jean Eustache.

************************************

August

After the usual slew of mediocre, family-friendly popcorn movies during the summer, the quality re-emerged in the Autumn with Oscar season commencing. After the relative failure of his first feature film, THX 1138 (itself a remake of his prize-winning student project), George Lucas, with help from his friend Francis Ford Coppola, released the breakout hit of the year in American Graffiti. This was an early 1960’s-set, nostalgia-driven coming of age comedy drama that had everything to please audiences – young and upcoming stars, groovy cars, sex with morals, and great music. It was a time before Vietnam and a breakdown of social norms, which in itself sounds terribly boring, but Lucas created something that was fun and everlasting. Like Truffaut, he allowed his movie to confidently create a complete fabrication of something that the audience could indulge in. Here the seeds of Star Wars were being planted.

A month previously, Bruce Lee died in Hong Kong at the age of 32 due to a swelling of the brain. He had just been putting the finishing touches to his latest movie Enter the Dragon, directed by Robert Clouse. We all know of the substantial legacy that Lee left behind, in particular his profile-raising of Chinese martial arts (kung fu), and we can be thankful that Enter the Dragon, arguably his most superior film, made it to the cutting room floor before he passed. More polished than Fist of Fury and The Way of the Dragon before it, Clouse’s film established all the hallmarks of future action films that would be made later for Chuck Norris, Jean Claude Van Damme, Steven Seagal, Jet Li and Jackie Chan. It also had a major influence on the Blaxploitation genre, Quentin Tarantino and Nintendo video games. Now that’s some impact…a karate chop of an impact!

Other notable films released in August were Michael Crichton’s Westworld (the original and best), the Robert Blake-starring and Chicago-scored Electra Glide in Blue, and Clint Eastwood’s Leone tribute High Plains Drifter.

************************************

October

From October to December 1973, I am not sure how anyone who was a keen cinema-goer back then could keep up with all the solidly brilliant releases coming through. It just reads like a veritable feast for the current-day cineaste! In October, Terrence Malick burst out of the traps with a stunning directorial debut in Badlands, a surreal, spellbinding masterpiece in cinematography starring Martin Sheen and Sissy Spacek. This was quickly followed by Nicolas Roeg’s Don’t Look Now, a chilling horror mood-piece set in Venice and featuring a graphic sex scene between two major Hollywood actors (Julie Christie and Donald Sutherland), which sent critics a bit crazy, and Sydney Pollack’s romantic epic The Way We Were that matched superstars Barbera Streisand and Robert Redford and no graphic sex.

Then came Mean Streets. Holy hell! The young Martin Scorsese was in with the same crowd as the already-established Coppola and Brian De Palma, and the burgeoning Lucas and Spielberg. He had some acclaim a year previously with Boxcar Bertha, a film produced by low-budget extraordinaire Roger Corman. The full breakthrough came with Mean Streets, which saw Scorsese work with Robert De Niro and Harvey Keitel for the first time. They were all about the same age and from working class Italian backgrounds in New York, and this is exactly what his film is about. Mean Streets was the template under which all subsequent Scorsese films would adhere to: bloody violence, grit, witty dialogue, flourishes of the camera, quickfire edits, troubled but engaging characters, street scenes, and a damn awesome soundtrack (always featuring The Rolling Stones). It’s rough around the edges, but the film never ceases to pulsate with kinetic energy.

Another notable film released in October was the Spanish film The Spirit of the Beehive from director Victor Erice – a sublime, unforgettable drama driven in every aspect by the six-year-old Ana (played by Ana Torrent). It is a marvellous film, so rich in symbolism and full of humanity. Its critique of fascist Francoist Spain was so subtle that it was undetected by the Government censors at the time but viewing the film today, the impact of historical context is inescapable.

************************************

December

So, in the run-up to Christmas, a Santa’s sack-full of movie treats graced cinema screens across the world. Clint Eastwood reprised his role as Dirty Harry in Magnum Force, his second big movie of the year. Veteran Henry Fonda returned to the spaghetti Western genre with a Sergio Leone-penned, Ennio Morricone-scored comedy in My Name is Nobody. Woody Allen, in his fifth feature, placed himself and Diane Keaton at the heart of a screwball futurist comedy called Sleeper. The always watchable George C. Scott headed up Mike Nichols’ so-bad-its-good Cold War thriller, The Day of the Dolphin. Disney brought out family-friendly Superdad, which has a young Kurt Russell. In Europe, Richard Lester directed an all-star line-up in the fourth adaptation of Alexandre Dumas’ The Three Musketeers (arguably the best one even to this day), and the irrepressible Federico Fellini continued his remarkable run following Satyricon and Roma with the semi-autobiographical serious coming-of-age comedy, Amarcord.

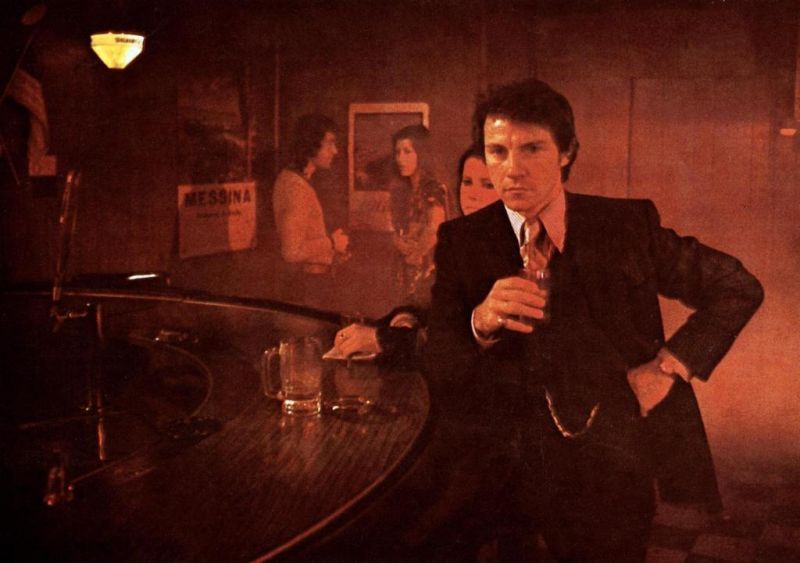

The work ethic of director Sidney Lumet was formidable. By 1973, he was approaching 50 and had 17 films behind him – this commenced with 12 Angry Men in 1957, which established an enormously high bar that he was unwilling to let go of. The Offence arrived in January, and then in December came Serpico, the first of four seminal films that marked Lumet as one of the greats. A stature-establishing, method-acting Al Pacino portrays the titular police officer who exposes mass corruption in the NYPD, and indeed this was a true story, based on a book by Peter Maas and a screenplay from Hollywood titans Waldo Salt and Norman Wexler. It is prime, gritty 70s cop action, but its also measured and deeply affecting stuff. I remember seeing this for the first time on TV during a special Pacino season around Christmas time, and I was blown away by the rawness of his performance and the sheer weight of emotion that the content invoked.

The Wicker Man was first released to limited outlets in the UK at the start of December 1973, but had a bigger release in January 1974. It was distributed by Roger Corman to US cinemas later that year, but as the story goes, its running time was cut and the narrative lost continuity, and the film subsequently failed with audiences and critics. This is how Robin Hardy’s The Wicker Man drifted into obscurity only to be later picked up as a cult folk horror classic – one would argue the first example of the folk horror genre. It is a fruitfully original film, one that is frightening, exciting, intriguing, and totally batshit crazy. Edward Woodward plays the straight-up, repressed policeman to perfection and his genuine horror at what unfolds is still chilling to the bone no matter how many times you watch this. Christopher Lee is Christopher Lee, and there is no other way you want to see him on film. A true horror legend.

My parents didn’t have many films on VHS – we always rented them – but on the shelf alongside The Great Escape, The Lady and the Tramp, The Sound of Music and a TV movie starring Jack Palance (can’t remember the name of it) was Franklin J. Schaffner’s Papillon. Because it was there, I watched it a bunch of times when I was younger. I watched it again recently, and it remains for me a great, great movie. It has the tropical South American settings, the two superstars in Steve McQueen and Dustin Hoffman, the prison escape drama, the sparse dialogue, uncontrollable teary moments, and a tremendous score by Jerry Goldsmith. I spoke about McQueen’s screen presence before, and I think it soars here, particularly given that he speaks very little and instead allows his body and his expressions to do all of the talking.

Obviously, the male star duo thing was big in the seventies, and after the success of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid four years earlier, audiences were panting in their thirst for more superstar shenanigans from the Paul Newman/Robert Redford pairing. Truth be told, The Sting is one of my favourite films of all time, and Newman and Redford are just fantastic, magnetic actors no matter what they are in. The film is one of the most perfected crime-capers ever committed to celluloid – it established the blueprint for modern films like it. I just love it. People say that other, far better movies existed in 1973 and deserved the Best Picture at the Oscars in March 1974, but whereas it was a fucking difficult choice, I think George Roy Hill’s masterpiece deserved it as much just as the others did. It also stands out because it replaces the expected 70s grittiness with a refined, Golden Age-inspired stylishness that makes it accessible to all audiences. One may accuse it of being a crowd-pleaser, but if that is what it is and it succeeds, then so be it. It is a massively entertaining watch and the bold Robert Shaw as a villain in anything is worth the price alone.

So, The Sting came out in the US on Christmas Day 1973, and The Exorcist came out the following day. Nevermind your ‘Barbenheimer’, what about ‘The Stingorcist’? As far away in content and form as The Sting, but every way its equal in terms of quality, William Friedkin’s The Exorcist is rightfully placed as one of the greatest films ever made and a gamechanger in the horror genre. Hands-down one of the scariest films ever created, its legacy is as important as its impact when it was released, which unsurprisingly unleashed a tsunami of controversy – it effectively challenged the status quo around sensibilities and established creditability and mainstream aspirations to horror writers and filmmakers. I think many people say now that the film’s infamous treatment of religious themes pales in comparison to more modern works, but no doubt at the time there was a power to what was being presented. And this was always Friedkin’s intent. The Exorcist is still very much in date and a powerfully authentic watch every time. It is endowed with exquisite cinema magic and lore, and the acting is of the highest calibre from both young (Linda Blair) and old (Lee J. Cobb).

Astonishingly, Hal Ashby’s The Last Detail (with Jack Nicholson, Otis Young and Randy Quaid offering the best mis-matched trio in cinema history), and Rene Laloux’s animated classic Fantastic Planet, were also released in December 1973, and this just reinforces how much of an annus mirabilis it was for film. Utterly remarkable, and if you have not seen all of the movies mentioned above, what are you waiting for? You won’t be disappointed!