You said it would last, but I guess we enrolled in 1984

‘1984’ by David Bowie

The year 1984 was peak ‘eighties’ in terms of pop culture (the second season of Stranger Things certainly embellishes this notion). Rolling Stone consider it ‘Pop’s Greatest Year,’ with endless radio plays now guaranteed for classic tunes such as Queen’s ‘I Want to Break Free,’ Bruce Springsteen’s ‘Born in the U.S.A.,’ Don Henley’s ‘The Boys of Summer’ and a-ha’s ‘Take on Me’. Madonna chimed about being ‘Like a Virgin,’ Arnold Schwarzenegger told us “I’ll be back,” Wendy’s asked “Where’s the Beef?” and Apple introduced their first Macintosh computer proclaiming that it would not be anything like George Orwell’s novel…how’s that working out, Apple?

For children of the eighties, it certainly appears to have been a special year. Despite the Star Wars saga ending for the time being, a second, albeit less exciting, Indiana Jones movie was released in May, while Ghostbusters, Gremlins, The Karate Kid and The NeverEnding Story followed in a summer to remember at the movies. There were other special cinematic moments for younger viewers throughout the year: Kevin Bacon dancing like a lunatic in Footloose, Harold Faltermeyer’s ‘Axel F’ instrumental theme in Beverly Hills Cop, Daryl Hannah as a mermaid in Splash, the unforgettable characters of Jones, Tackleberry, Hightower and Mahoney in the first instalment of Police Academy. These are all things that I remember and I wasn’t even born in 1984! But of course, in time you catch up.

Let’s have a look at some of the best and more interesting films from 1984 (40 years ago this year!) on a month-by-month basis, noting that some months were much higher in quality than others.

***********************************

January-February

The traditional post-Christmas awards season always sees a number of aspiring films enjoying a long release from December into February, and in 1984, this included James L. Brooks’ Terms of Endearment and Mike Nichols’ Silkwood. The former enjoyed the biggest success with five Oscars, including Best Picture, Shirley MacLaine as Best Actress, Jack Nicholson as Best Supporting Actor and Brooks as Best Director. The latter film didn’t win anything despite a strong cast that included Meryl Streep, Kurt Russell, Cher and Craig T. Nelson. However, whereas both films have their strengths I find Silkwood more compelling, mainly because it offers a punch-packing realism about working class life and Government cover-ups in Mid-West America. Another film that was robbed at the Oscars in 1984 was Peter Yates’ The Dresser, a British drama set exclusively in a theatre where an ageing actor prepares to perform Othello. Albert Finney as the actor and Tom Courtenay as his dresser are something to behold in terms of their performances.

After enjoying a promising reception at the Colorado Telluride Film Festival in 1983, Gregory Nava’s El Norte was released worldwide in January 1984. It was the first Latin American to be nominated for a Best Original Screenplay Oscar (in 1985), but I am unsure why it was not nominated for Best Foreign Language Film given that much of the dialogue is in Quiché and Spanish. Perhaps this had something to do with the funding it received from PBS. But regardless, it is a film that deserves a lot more recognition. The harrowing story follows two Indigenous Mayans from a small Guatemalan village as they flee Government-inflicted violence to search for a better life in the US. It is a magnificent travelogue film that combines aspects of Mayan spiritualism and magical realism with a story of tear-jerking human drama and tragedy.

***********************************

March

Possibly one of the freshest films of the decade came out in early March. Repo Man. What an awesome movie. It has the catchy name, the surreal storyline, the quirky in-film details, and the mad behind-the-scenes trivia that has contributed to an all-hailing cult fandom over the years. And it stands out as a film of the eighties, even though there is nothing quite like it from the eighties either. Briton Alex Cox had scored the somewhat fortuitous gig in Hollywood after he moved there to study in the late 70s and propositioned his script for Repo Man. The Monkees’ Michael Nesmith was one of the executive producers. Starring Emilio Estevez (breaking out of the Brat Pack) and Harry Dean Stanton (the man, the legend), the film follows the misadventures of a couple of car repossession hacks as they pursue a 1964 Chevy Malibu apparently holding precious cargo in its trunk. And that’s not half the story. It’s a satire of US consumerism in the Regan Years, and there is a bit of proto X-Files stuff going on. Add to that a hardcore punk score by Iggy Pop and the Stooges, and mesmerising photography of downtown LA by the visionary Robby Müller, and you have an instant re-watchable classic.

On the same day as Repo Man, ‘the funniest rock movie ever made’ was released. This is Spinal Tap. It threaded a not too dissimilar path to Alex Cox’s film in that it didn’t find much success initially, but then became a cult favourite after video release. However, over the years, This is Spinal Tap has been established as a household name and one would argue that its cult status is kind of bogus now. The key ingredient to the film’s magic is undoubtedly its trio of comic stars: Michael McKean, Christopher Guest and Harry Shearer (they developed the idea with Rob Reiner years before). Their pitch-perfect dialogue, endlessly repeatable quotes and comic timing is a treat every time. They went on to make many more mockumentaries and cinéma verité parodies (all of which are great too), but you just can’t beat a film that has an amplifier that goes up to eleven and a Stonehenge replica prop that you could fit in your pocket.

In Japan, a momentous occasion in animated film occurred in March. Hayou Miyazaki’s Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind was released with major success that fed into the creation of Studio Ghibli a year later. Nausicaä harked back to all of Miyazaki’s previous work in TV and manga (itself an adaptation of his comic series) and it also established many future trademarks of the Ghibli universe – a young adult story, post-apocalyptic worlds, environmental issues, and strong female characters. It was also, and remains to be, a beautifully-formed piece of artwork. Some will point out that Miyazaki’s animation has improved over time, which it has, but with Nausicaä there is a sense of flourish and excitement to its creation. This, after all, was the first time Miyazaki was given adequate money to realise his visions of weird mutant creatures and steampunk craft. It is a stunning film with heart, passion and common-sense in abundance.

***********************************

April-May-June

The early summer releases of 1984 from Hollywood did not offer too much, but there was one film that stuck out that often gets overlooked nowadays. On the surface, The Natural threatens to be an all-American slice of schmaltz, but in the tradition of genuinely quality Hollywood movies about baseball (which continued throughout the eighties and nineties), Barry Levinson’s film is quite brilliant. It recounts the fictional life and career of Roy Hobbs, a naturally-gifted baseball player who has dramatic and sensational ups and downs as a professional in the 1920s, 30s and 40s – this invariably involves a delve into the murky world of sports bribes and betting, as well as a bit of murder intrigue. Robert Redford indulges in his charming persona to produce a magnetic performance as he always does, while Glenn Close, Kim Basinger, Barbara Hershey and Robert Duvall head a delectable supporting cast.

As the summer progressed, the blockbusters increased (as indicated in the introduction above). Star Trek III: The Search for Spock, although it sounds bad, firmly holds its place in the Trekkie-canon and ticks off on all the Shatner/Nimoy requirements. Other enjoyable summer romps included the Zucker Brothers’ daft Val Kilmer debut, Top Secret!, a return of Burt Reynolds’ J.J. McClure in Cannonball Run II, and Arnie’s muscly follow-up as Conan the Destroyer. A less enjoyable but massively superior film is Sergio Leone’s magnum opus Once Upon a Time in America. At Cannes, the film was shown in its original cut of around 4 hours duration and it received a raucous ovation. But for some ludicrous reason, The Ladd Company decided to cut the film back to just over 2 hours for its US release, completely destroying the narrative, making the film a box office bomb, and ensuring that Leone was so pissed off that he would never make another movie. Well done, guys! Thankfully, the original cut (as well as others) is now more widely available, and you can witness the sprawling epic story about the Jewish mafia in New York throughout the early 20th Century as Leone intended. Add to that Ennio Morricone’s haunting score, solid performances by Robert De Niro, Elizabeth McGovern and James Woods, and a unique, mood-filled atmosphere. There is a troubling embodiment of misogyny and sexism pocketed throughout and when sided along with Leone’s other films, you can see this as a personal trend. But after all, this is a story about, and some would say a critique of, male-dominated violence, corruption and greed.

***********************************

July-August

When looking at the less starry summer releases of 1984, a few examples pop out. The Last Starfighter, directed by Nick Castle, was an innovative teen sci-fi movie – it ticked off the requirements of Star Trek-styled aliens and arcade computer games, and these were two very important things for kids of the eighties. Sheena, a superhero action-adventure directed by John Guillermin, was a laughing stock to many, but over the years it has been re-evaluated in the ‘so bad, its good’ category. Tanya Roberts was panned as a Playmate-styled blonde goddess, but there is so much more to appraise here and I would rate it much higher than the male-version of the story, Greystoke: The Legend of Tarzan, Lord of the Apes, released earlier in 1984. The rock opera Purple Rain was also released in the summer of 1984, and although it is not the greatest film you will ever see, it does have a delightful charm and charisma and of course, the music and presence of Prince is really the only excuse you need. A few other random suggestions I would offer from this period of cinema would be The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai Across the 8th Dimension, a comedy where Peter Weller, Ellen Barkin, John Lithgow, Jeff Goldblum, and Christopher Lloyd play alternative ‘Avengers’ saving the world against aliens, and Wheels on Meals, a hilarious Jackie Chan-Sammo Hung martial arts vehicle that zings just as much as that title.

***********************************

September

Amadeus, the Best Picture Oscar Winner in 1985, was released in September. Described as a fictionalised account of Mozart’s life and lauded as a powerful work, I must say that it never really sat well with me. Perhaps because I struggle with period pieces in general. But also, I think there were so many worthier films from 1984: Wim Wenders’ Paris, Texas for example, which was released around the same time (discussed in detail here). And what about Jim Jarmusch’s Stranger than Paradise (released in October)? Jarmusch received mentorship from Wenders as well as Nicholas Ray in the run-up to making this film, and you can clearly see their influences. It offers the minimalist story of low-life New York hustler Willie (John Lurie), his friend Eddie (Richard Edson) and his recently arrived cousin from Hungary, Eva (Eszter Balint). They all hang out in often mundane circumstances, mostly irritating each other with their quirks and idiosyncrasies, but ultimately seeking something better than the state they are currently in. The power of the film mostly lies in Tom DiCillo’s photography – black and white, and focusing on desolate, derelict landscapes and grimy cityscapes – but the fact that Lurie, Edson and Balint were all musicians rather than actors when Jarmusch created the film also contributes to a very effective realism. It is one of my favourite arthouse films.

Across the pond around this time, Irish director Neil Jordan adapted Angela Carter’s short story The Company of Wolves into a film. Carter worked with Jordan on the screenplay and her story is essentially a retelling of ‘Little Red Riding Hood’ but with an intense focus on gothic horror. And given Carter’s credentials as a powerful feminist novelist, the film carries symbolic weight particularly through the young lead Sarah Patterson. The visual design is indeed a bit dated now, but Jordan works admirably within the parameters of a small budget and creates an effective, menacing fairytale with just the right amount of kitsch thrown in. He would go on to direct Interview with the Vampire in 1994, another gothic horror adaptation, which sits quite nicely as a companion piece to this underrated gem.

***********************************

October

October 1984 appears to have been the month when darker, more adult films took centre stage. The often controversial and perennial risk-taker Ken Russell was called upon to direct a screenplay by Barry Sandler that tapped into the sexual mores of US society at the time, and this was released as Crimes of Passion, starring Kathleen Turner (fresh from the commercial success of Romancing the Stone) and Anthony Perkins (a B-movie regular after the success of Psycho two decades earlier). Derided by many as an attempt at mainstream porn, I think it has much more going for it than that. The general gist is that a man whose marriage is on the rocks gets caught up in the fetishist world of a sex worker. A psychotic evangelic preacher is obsessed with the sex worker and well, it all heads for a very tense climax (pun intended). I was brought to watch this film after listening to Karina Longworth’s You Must Remember This podcast, where she examined the impact of the erotica on audiences and critics back then as well as how it stands up today. She also discussed Brian De Palma’s erotic thriller Body Double (starring Melanie Griffith) in the same context, a film that came out at the same time. Her thoughts were that whereas Crimes worked hard to communicate a deeper meaning about religion and sex in eighties America, Body Double was more interested in shallower viewpoints such as voyeurism and a perceived emasculation occurring in American society. I can’t disagree there, but I would argue that both films are definitely worth a watch for their intrigue and social commentary.

Also released in October were James Cameron’s seminal sci-fi action classic The Terminator, which made ten times the value of its fairly modest budget and jettisoned Arnold Schwarzenegger into superstardom (I’m still unsure why it didn’t do the same for Linda Hamilton, but wait, I can). The little-known Coen Brothers also came to festival circuit prominence at this time with their debut Blood Simple, which is an intriguing dark crime comedy and introduces their trademark wit and penchant for brutal violence. Jonathan Demme’s glorious Talking Heads live concert film Stop Making Sense also received a wide release at this time, and boy is that a film to watch, not just for the awesome music, but also for the style and charisma of David Byrne and the quality of the sound recording.

***********************************

November-December

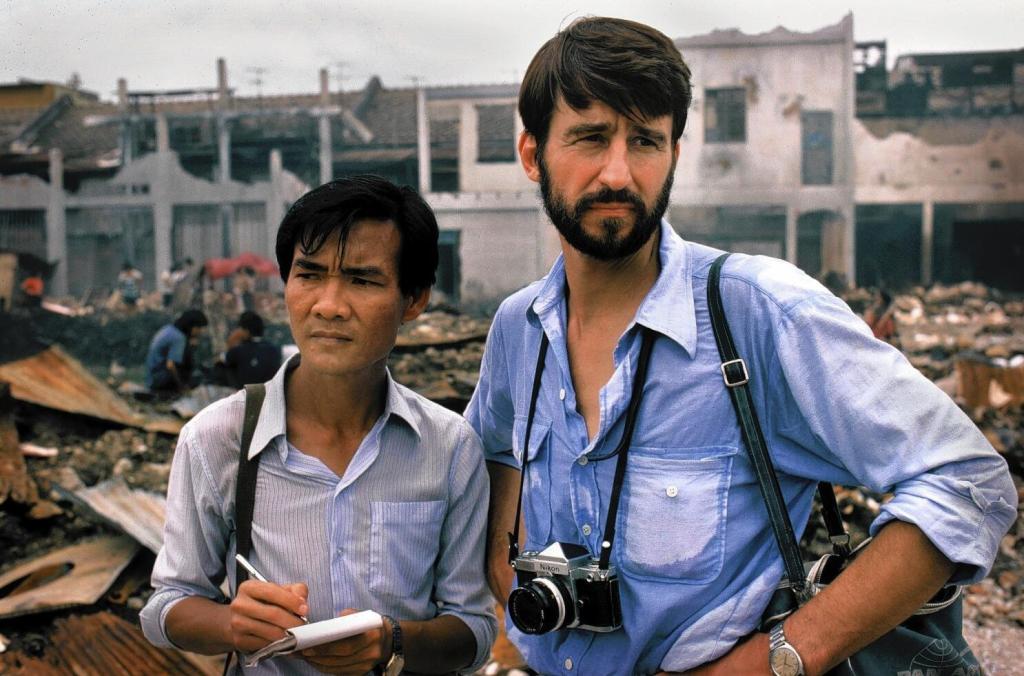

The awards season kicked off In November and inevitably, a high-budget historical drama intent on taking all the awards home was to be released at some point. Enter Roland Joffé’s The Killing Fields, a British production stemming from Withnail and I’s Bruce Robinson’s robust script. The film accounted for the brutal Khmer Rouge regime in Cambodia from the 1950s through to the 1970s (still fresh in many minds) as told through the story of two journalists played by Haing S. Ngor and Sam Waterston. It is not the usual blend of sentimentality and condescending Western viewpoints that often permeates these types of films, but it does have a rawness and an angry passion, which makes it stand out. The Brits weren’t done with historical epics there. A bit of money was thrown behind the ageing master of the screen, David Lean, with his last hurrah, A Passage to India, released in early December. The acting royalty in Dame Peggy Ashcroft and Sir Alec Guinness were drafted while Australian Judy Davis, James Fox, Nigel Havers and Richard ‘I don’t believe it’ Wilson were in the mix too. A Passage to India is a lush, sun-soaked, meticulously-made masterpiece, up there with Lean’s best. You would be forgiven for expecting Peter O’Toole to wander into scene on a camel, given the similarities the production has with Lawrence of Arabia. Based on E. M. Forster’s novel, it is a provocative story of class relations, rape and the effect of colonialism in India, and the result is stunning.

The last film to discuss is, surprise, surprise, Nineteen Eighty-Four, which was released in the UK in October but followed up with a wider release around the world at Christmas time (what a lovely time to sit down with the whole family and watch a film about a dystopian future where a totalitarian Government watch your every movement and torture you if you step out of line!). It was highly anticipated given the symbolism of the year it was being released in, but it was not the first time George Orwell’s infamous novel had been adapted for the big screen – the first occurred in 1956 in a film by Michael Anderson starring Edmond O’Brien and Donald Pleasence. Michael Radford’s version is most definitely superior. With John Hurt as the spiralling civil servant Winston Smith and Richard Burton (in his last role) as the evil undercover agent O’Brien are perfectly cast, with Hurt typically embodying the role he has committed to. The adaptation by Radford is very bleak. It recalls gritty British ‘kitchen sink’ dramas of the previous decades and taps into the vibe of societal cynicism and anger that was coming from the likes of Terry Gilliam and Alan Clarke at the time. It is by no means a high-quality rendering of Orwell’s masterpiece, but nothing could ever do that justice. The impact of ideas such as Big Brother, the Thought Police, the Ministry of Truth, doublethink, and the horrors of Room 101, will be forever held in the book, but between Radford, Hurt, Burton and Roger Deakins cold photography this was a solid attempt at visualising the content (which is more than can be said for David Lynch and his bizarre adaptation of Dune, which came out on the same day).