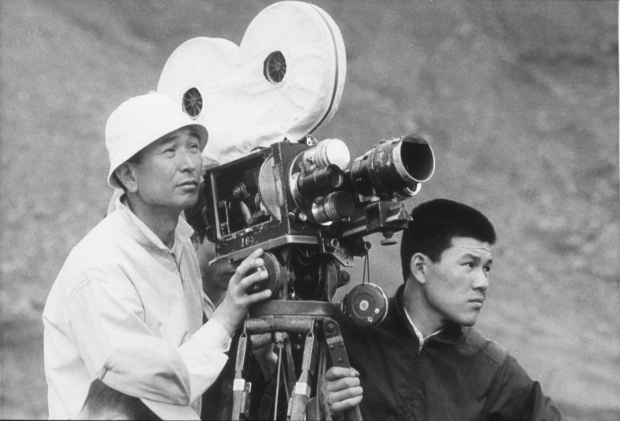

Akira Kurosawa (黒沢 明 1910 – 1998) was a master of film craft, and one of the greatest directors of all time. He grew up in Tokyo, watching silent films from around the world and going to see traditional and modern Japanese theatre. He became a painter, and in his 20s got into script writing, editing and then assisting with film direction; skills that are evident in his films. He was influenced by the democratic and humanist ideals emerging in the post-war period. He made over 30 films, some of which remain among the greatest known Japanese films in world cinema.

Kurosawa’s themes are often humanist in nature, shaped by a developing post-war consciousness, and utilising traditional Japanese storytelling techniques and film devices and cinematographic symbolism common in Western films. In the post-war period, the expertise with which he incorporated these elements struck a chord with many. And though he made several samurai films – what might loosely be called action films – he constantly introduced the struggle of ideas in shaping individuals. His earlier films were subject to both Japanese and US censorship, and different versions were often released in the US or Europe than what was shown in Japan. Despite these impositions, Kurosawa is considered one of the greatest directors of the 20th Century.

This is the second post in a ongoing series of posts on the films of Akira Kurosawa. In this post Robin Stevens takes a look at perhaps Kurosawa’s most famous film of all: Seven Samurai.

*************************

Preamble

The film in its entirety was shot between May 1953 and March 1954, seven months longer than the three months planed. It was the longest and most expensive Japanese film made up to that point. It cost a massive $US560,000 (five times the usual cost), almost sending the production company Toho broke. Kurosawa was nearly replaced, but he made sure not to shoot the pivotal scene until late, forcing them to keep him on. Its instant success in Japan and around the world was however very profitable for Toho productions. The full 207 minute Japanese version of Seven Samurai has never been shown in an American cinema, and has only recently become available on DVD and Blu-ray.

The Film

Seven Samurai (七人の侍 Shichinin no Samurai) is Kurosawa’s most famous film. Released in 1954 to immediate international acclaim. Akira Kurosawa co-wrote, directed and meticulously edited this film. Set in 1586, it portrays the efforts of village farmers in hiring seven samurai or ronin (wandering samurai who have no master employer) to defeat marauding bandits who are intent on stealing their harvest crops. They have nothing to offer as payment except rice. Three farmers travel to the nearest large town in the hope of finding ronin prepared to fight for food. And that’s the basic story. There is something very humanist and very appealing about fighting to help the underdog; and it draws the viewer in. You want them to succeed.

The film opens with a wonderful score by Fumio Hayasaka, with slow beating drums, somewhere between a military march and a funeral march. Dark clouds move across the sky. Kurosawa had a very high regard for Hayasaka, whom he had asked previously to write the scores for Rashōmon (1950), The Idiot (1951) and Ikiru (1952). The ominous mood is set with dark skies and sombre music, as it slowly ramps up to a menacing volume.

We see the bandits but we never really get to know them. We don’t know their names or any real differences between them. They are a menacing mob. The seven samurai, on the other hand, have very distinct personalities and mannerisms. Kurosawa wrote or co-wrote many of his films, and made detailed notes for his other scriptwriters, often detailing precise mannerisms for each character. For Seven Samurai, he created extensive biographies (six whole notebooks) for each of the lead characters, and also worked out the number of families, family relationships and daily work and social habits of farmers in the entire village. In Seven Samurai, Rashōmon and other films he asked lead actors to develop a particular body movement or idiosyncrasy. Mifune in Rashōmon had a twitchy shoulder and would often scratch his jawline or smack a mosquito on his neck. He further developed exaggerated shoulder movements in Seven Samurai and also erratic facial expressions, from squinting eyes to raised eye-brows. He reacted non-self-consciously in great animated movements. Takashi Shimura, another favourite actor-collaborator of Kurosawa, appearing as the group leader in Seven Samurai often rubbed the small bristles atop of his head as he contemplated some course of action. This was nicely mimicked by Yul Brynner in The Magnificent Seven (1960), a fine American version of the film.

Breaking with Tradition

Prior to World War II, a glorified and idealistic samurai ‘honour’ was instilled in the imperial army – a kamikaze style dedication. There was honour in death. The post-war US occupation strictly censored film scripts prior to their production. Samurai films, in particular, went out of fashion as they tended to celebrate a fight-to-the-death Japanese nationalism. This lasted until occupation ended in April of 1952. In Seven Samurai, Kurosawa made one of the first samurai films following the end of this strict censorship. However, he also did not care greatly for the pre-war simplified, nationalistic view of samurai honour, nor its legacy in contemporary Japanese consciousness. He decided to make a samurai film that was more historically accurate and more morally conflicted. Nonetheless, Seven Samurai was still substantially cut prior to US release. This was partly a commercial decision, and partly a result of American concerns about Japanese films celebrating heroes fighting honourably to the death.

In any event, Seven Samurai broke with a Japanese tradition of samurai films that oozed nationalism (Rambo-style heroes). Kurosawa put samurai films back on the screen, but this time they were grittier and truer to life. More than that, they questioned the pre-war nationalism and distorted military prestige. A critical scene in the film is when we first encounter Shimada (Takashi Shimura), prior to becoming the samurai leader. He is shaving off the top of his hair; a shameful thing for a samurai. Local villagers are mesmerised by the act. He does this to disguise himself to a dangerous thief who is holding a child hostage. Unarmed, he intends to save the child. His honour and his pride takes second place to the nobler act of self-sacrifice in the service of those in need. It is this ideal, this more modern sensibility in serving the people, rather than some elitist chivalry, that Kurosawa is championing. Did I say how much I like Kurosawa?!!

At a critical point in the film, on the eve of the first attack by the bandits, the Samurai learn that the farmers have lied to them; they have hidden food as well as their women because they don’t trust samurai even though some samurai may die in helping the farmers. The samurai are outraged at the indignities. The most powerful speech in the film brings them to an abrupt halt. Kikuchiyo (Toshiro Mifune), a turmoil of anger and hurt emotions, turns on them. In his angry outburst it becomes clear that he is actually an orphaned farmer, barely coping with his pain. Yes, he says, the farmers lie and cheat, and they don’t trust samurai, but continues…

“…tell me this: Who turned them into such monsters? You did! You samurai did! Damn you to hell! In war, you burn their villages, trample their fields, steal their food, work them like slaves, rape their women, and kill them if they resist. What do you expect them to do? What the hell are farmers supposed to do?”

The samurai fall into guilt-ridden silence. This is an up-turning in the narrative, where the farmers, the samurai and the bandits are all guilty. It’s a bit like the allegorical narrative in Rashomon, where notions of righteousness are mediated through heavily filtered perspectives. The consequence of this piece of high-drama is that the traditional hero samurai, the superficial super-heroes, are humanised. More than that, the ‘ordinary folk’ around them play a greater role, not just as a helpless amorphous mass, but as partners. We feel good, don’t we? Anyhow, I’m not sure I agree with a popular view among some film critics that Kurosawa thought there was something ‘ideal’ in samurai notions of self-improvement and honour, with the proviso that such ideals had to be modernised. Maybe, but that’s not quite it. I’m more inclined to believe that in this film, as in many of his other films, he sees good and bad in people, but that good is the winner when people come together to support each other; and they can only do this if they can see their own faults.

Violence: Aesthetics vs Realism

The first scenes of fatal conflict in Seven Samurai are understated. They are slow one-on-one combats. The camera catches the aftermath more than the action. The killing of the thief and the duel between Kyūzō (Seiji Miyaguchi) and an aggressive but wayward opponent, are two such examples.

One of the most impressive visual elements of the film – and a breakthrough in cinematic visual effects – is Kurosawa’s slow-motion fall of the thief (see image above). The interesting thing about this scene is that the camera moves between slow-motion and real-time motion to create an impacting moment. And while the thief stumbles in slow-motion, almost frozen before he falls, a child can be heard crying without any slowed down effect. His mother rushes forward and then the thief falls to the dust. Part of the effect of this scene is that Kurosawa cuts between the village observers’ reactions to the stumbling thief in real-time and the thief’s slowed down motions as his life slows to a stop. The visual impact of this is staggering, but it is also replete in symbolism. Later directors have used slow-motion death scenes enormously, especially in action films, but none of them quite pull it off as Kurosawa does in this scene. I think the key difference is that this scene is about life coming to a stop, rather than the weaponry prowess of the protagonist. Anyhow, it’s a piece of genius.

The second scene is where the quiet but masterful swordsman Kyūzō is confronted by a jumped-up farmer, and a duel results (see image above). In contrast to the aggressor, Kyūzō is calm and deliberate in his movements, almost elegant. He knows exactly what he is doing. Again, Kurosawa cuts between the observers’ reactions and the duel itself. We already know there is to be one outcome given Kyūzō’s professionalism and skill over the farmer’s amateur enthusiasm. Although the violence is not highlighted, it is the tension before or after that is elevated. Both scenes demonstrate that the samurai are cool masters of combat, with clinical but deadly skills. They think before they strike.

Kurosawa used slow-motion to convey emotion (the quick realisation of shock slowed down for great effect), particularly in portraying fatal violence in aesthetics – to be admired and awe-struck. He did not exactly celebrate fatal violence (not in the way so many American action films do), but he did bring an aesthetic quality to death on film. Often using dramatic close-ups of faces as they take their last breath, cry out in pain or fall to the mud. He used slow-motion effects to focus attention on the moment of death. And he does not usually blot out background sound, but uses it to contrast life going on as the subject’s life is closing.

But this is not the case in the chaos of a crowd battle, in which violence is unrestrained and often messy. Kurosawa began using telephoto lenses in Seven Samurai to great effect. This enabled him to shoot at a distance numerous scenes of fast-paced chaos in the throes of battle, which bring a vitality and energy to the film. For example, the lens capturing the dramatic fall of Kikuchiyo (Toshiro Mifune) or one of the bandits between the legs of a charging horse. The sequence of the battles in Seven Samurai portray extraordinary savagery (given this is a 1950 film). Mud and rain add to the chaos; a kind of unfettered release of mayhem from nature itself (see video of the most famous battle sequence here).

Kurosawa filmed battle sequences with lenses set to long, medium and short focus. Unlike the graceful aesthetic of Kyūzō’s duel, the use of multiple cameras with cross-cut focal lengths, and rapid movements brought a gritty realism to the scenes in all their violent horror and weather-lashed conditions. Distorted and tormented figures die in confusing and difficult chaos, often in slips and falls. There is nothing fine or majestic about it.

The Romantic Lull

A budding romance in the film provides welcome relief to the gradually building tension towards a deathly showdown. But it is, I think, also to show that in the midst of death there is hope for a new beginning. That might just be the romantic in me, but Kurosawa did not put scenes in his films without usually having some deeply considered perspective. The youngest samurai, Katsushirō Okamoto (Isao Kimura) falls for a village girl Shino (Keiko Tsushima). Her father cut her hair and made her wear boy’s clothes so that the Samurai might not notice her; but of course that was never going to work, was it? I like this romantic interlude, laced with some beautiful tender moments and dreams of some worthwhile future (see images below). Their scenes are often in the seclusion of the nearby forest, flowers a plenty. They are often laying down, crouched or leaning in towards each other in a kind of sweet but secretive affair. When her father discovers the relationship he is in a rage, and hits her until Shimada intervenes. It is the only real part of the film in which a woman plays a significant role.

However, there is a brief but moving scene that includes another woman shortly after. Towards the end of the film, in between the slayings in the mud, the samurai pre-empt a strike against the bandits’ camp and burn it down. Farmer Rikichi (Yoshio Tsuchiya) helps the samurai break down the door of a household, when he suddenly sees his wife, who had been kidnapped in a previous raid and forced to be a concubine. On seeing her husband, she walks back into her burning hut and perishes. It is a reminder that men are usually villains or heroes in times of conflict, but women are always victims.

Hope After Destruction

Back to the scene, samurai Heihachi (Minoru Chiaki) is killed trying to save a devastated Rikichi. We’ve returned to self-sacrifice. Is this humanism or samurai honour in dying? It’s the former surely. The difference between other samurai films and this one is that samurai and farmers alike are dying for the cause. There is a sense of justice, and not some misplaced notion of military-style honour. The following year after Seven Samurai was release (1955), the award-winning and visually beautiful three-part film Samurai (I – III) by Musashi Miyamoto does go in for the ‘samurai honour’ orientation, and though it is a well-made film, I just wasn’t invested in it. It is all masculine honour and prowess in the end; so obvious in later Kung-Fu films. Fun for sure, but not in the same league as a Kurosawa samurai drama. There’s no depth to them. And perhaps that is an important point: while most samurai films are action films, Kurosawa’s samurai films have great action but they can perhaps be better described as dramas.

The samurai and the farmers win at great cost. Four Samurai and several villagers are dead. Kambei reflects on the battle over the past weeks: ‘In the end, we lost this battle too’, he says. But around him village life springs back, people are in the fields, the sun is shining. There is hope after destruction, Kurosawa is saying, and this is mainly down to the humanity shown by the seven samurai…

3 thoughts on “Akira Kurosawa – A Master of Film Part 2: The Humanity of the Seven Samurai”