Akira Kurosawa (黒沢 明 1910 – 1998) was a master of film craft, and one of the greatest directors of all time. He grew up in Tokyo, watching silent films from around the world and going to see traditional and modern Japanese theatre. He became a painter, and in his 20s got into script writing, editing and then assisting with film direction; skills that are evident in his films. He was influenced by the democratic and humanist ideals emerging in the post-war period. He made over 30 films, some of which remain among the greatest known Japanese films in world cinema. Kurosawa was nicknamed ‘The Emperor’ in the Japanese film industry. It is part-compliment, part-criticism. He tended to ‘command’ all of the most essential elements in his films: from conditions upon actors to editing, scripts and cinematography. It is clear that his views on how a film should look and feel was key to its success. He surrounded himself with consummate actors, script writers, cinematographers, score writers and other technicians, many of whom worked with him on multiple films and generally spoke highly of him. But ‘lesser’ actors often felt harassed or that the conditions they worked in were harsh. But none of them seriously dispute his genius.

Kurosawa is perhaps the most accessible and most successful Japanese film maker in the world. His themes are often humanist in nature, shaped by a developing post-war consciousness, and utilising both traditional Japanese storytelling techniques and film devices and cinematographic symbolism common in Western films. In the post-war period, the expertise with which he incorporated these elements struck a chord with many. And though he made several samurai films – what might loosely be called action films – he constantly introduced the struggle of ideas in shaping individuals. As an audience, we move from a mass to the individual (a touch like an inverse of German expressionism in silent film). His earlier films were subject to both Japanese and US censorship, and differently-cut versions were often released in America or Europe than what was shown in Japan. Despite these impositions, Kurosawa is considered one of the greatest directors of the 20th Century. Several of his films have been adapted into Western productions.

This is the final part in the Akira Kurosawa – A Master of Film series. Part 1 (by Robin Stevens) took a look at one of Kurosawa’s earliest and most iconic films, Rashomon. Part 2 (also by Robin Stevens) discussed the portrayal of humanism in the action masterpiece Seven Samurai, and Part 3 (by JJ McDermott) focused on Kurosawa’s ‘Autumnal era’ epic Dersu Uzala. Here, JJ McDermott focuses on his epic war drama from 1985, Ran – a film loosely based on William Shakespeare’s tragedy King Lear.

*********************

Ran (乱 – can also translate as chaos or turmoil) is quite simply a masterpiece. An unrivalled work of art. It is an example of a master film-maker reaching his peak in artistic output. What is amazing is that it was released in his later life, long after he had established himself as one of the greatest directors in the world of cinema. His creation of masterpiece after masterpiece in the 1950s, 60s and 70s was quite extraordinary, but in 1985, at the age of 75, when you would have thought he had expended all of his creative energy, Akira Kurosawa gave us a film so immense in scale and so high in calibre that one could argue that it dwarfed all his other films before it. I know that is controversial to say but there is no film that has demonstrated the power of cinema to me more than Ran has. It was truly incredible the first time I watched it and still remains so after several re-watches. As Vincent Canby of the New York Times exclaimed upon its release:

Here is a film by a man whose art now stands outside time and fashion.

In the late 1970s, George Lucas was rolling in the cash monies after the major success of Star Wars, and having borrowed some elements from Kurosawa’s earlier work, he was bewildered to find that the grand master was struggling to find the right amount of money to fund his next project. After meeting up with him in California and witnessing the astounding script and hand-drawings of his proposed project, Lucas recruited fellow Kurosawa enthusiast Francis Ford Coppola to put the finance together for it. That project ended up being Kagemusha (translated as The Shadow Warrior), a startling epic drama set in the Sengoku period (16th Century) and starring Tatsuya Nakadai as both a dying great lord (daimyo) and a thief employed to be his double. The film was cold, bloody and directed with every ounce of mastery available to Kurosawa. Some astounding cinematography, epic battle scenes and a feeling of Japanese mystic ensured that it was a huge success around the world, winning the Palme d’Or at Cannes and a nomination for the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film in Hollywood. It re-established Kurosawa as a box-office force, not only for Western audiences but in his home country too. It also allowed him to dictate a huge budget for his next project. As Kurosawa himself said, Kagemusha was just a dress rehearsal for Ran. And he wasn’t lying.

Tatsuya Nakadai as Lord Hidetora Ichimonji in Ran

His idea for Ran was sprouted well before Kagemusha, but as he foresaw a larger scale in production, he smartly shelved it until there was enough megabucks from willing studio companies available. The idea about a retiring lord and his three supposedly loyal sons who are each granted a third of his vast dominion hinged around the 16th century Japanese legend of a daimyo called Mōri Motonari. Initially the similarities with Shakespeare’s King Lear was incidental and it was only until the link was pointed out to Kurosawa that he purposefully procured further ideas from the play into his story. The end-product is something akin in profoundness to a Shakespearean tragedy, but on a stand-alone scrutiny there is something marvellously unique captured in Kurosawa’s filming – the colours, the outdoor staging, the attention to historical detail, and the chilling use (and non-use) of sound in a war setting.

…a series of human events viewed from heaven.

Hidetora offers each of his three sons (in blue, red and yellow) an arrow, as vassals look on

From the outset, Ran just swallows you up. The unforgettable opening scene, that in many ways could be a short film in itself, is like a series of paintings. The atmosphere is so taut and poised. The music eerily echoes forth in sharp clicking sounds and occasional flute twirls. Four warriors decked out in bright colours (each one different), sitting on horses, appear incredibly still as they keep a look-out on a spectacularly green hillside on a splendidly sunny day. One of the horses’ heads shakes breaking the trance we have been beckoned into. Soon we realise that these men are guardians of the powerful warlord Hidetora Ichimonji (played by Kagemusha’s Tatsuya Nakadai). He has come to the picturesque hills to take part in a boar hunt and speak with his three sons: Taro, Jiro and Saburo. His reason for this is to announce his plans to grant each of them one of his three castles. This we come to learn will be the beginning of not only a series of major feuds between the brothers, but also a descent into madness for the old man.

The film broadly bases itself around petty and spiteful familial disputes. Familial disputes that lead to grave suffering for the masses. Although Hidetora seeks to split his kingdom amongst his three sons, he bestows one of them (Taro) with the honour of being clan leader – however, he must still refer to his father as the ‘Great Lord’. This leads to another son (Saburo) questioning his father’s judgement and thus being banished from the kingdom for his apparent insolence. Later, Taro’s wife Lady Kaede, whose family was killed by Hidetora’s army, convinces her husband to completely usurp Hidetora so that he can take over the entire kingdom at the expense of Jiro’s castle. Kurosawa demonstrates that domestic drama between royal brothers and their father, aided by manipulative wives and vassals, can descend into civil war very easily. It is a chilling warning that most of the world’s ills and horrors can be initiated through basic human quarrels and selfish quests for power.

In a mad world, only the mad are sane.

A raving Hidetora looks to the heavens with his jester Kyomi (Peter)

Nakadai as Lord Hidetora, whether sane or having gone insane, is the greatest acting performance I have ever witnessed. His vivid and chilling reactions to events penetrate deeply on the viewer. He tacitly embodies the soul of a man completely consumed by power and then viciously betrayed by his own blood. You cannot but feel empathy for a man who has had everything and then loses it all when he decides to share it with others. But at the same time, we acknowledge the ruthlessness in which he has ruled his kingdom for so long, and wonder aloud if he should deserve such fate. It is no surprise to find that Nakadai played many Shakespearean and other tragic characters on stage before starring in both Kagemusha and Ran (including Hamlet, Othello, Macbeth and Oedipus). Taking on the role of a King Lear-styled character in Ran can be seen as the peak of his tremendous career. Now aged 86, he still is a highly regarded and decorated legend of Japanese stage and visual drama.

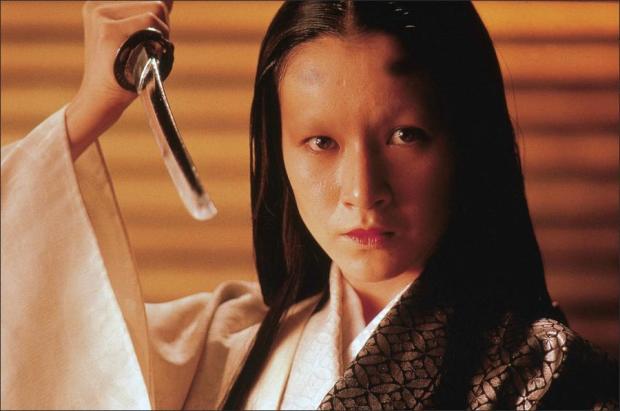

A brow-less Lady Kaede (Harada) holds her sword aloft

Mieko Harada’s performance as the evil and bloodthirsty Lady Kaede is also extraordinary. She plays a woman unfearful of the men who rule above her, merciless to others who threaten her, and patiently she awaits her opportunity to avenge the people who killed her family. Her snake-like movements in long flowing gowns and her expressionless face clearly signifie an untrustworthy presence. What’s more is that the men are in knots over what to do with her. She engages in psychological warfare with her husband Taro in order to control him, and she seduces her brother-in-law Jiro after Taro is killed, effectively managing to destroy Hidetora’s legacy with her actions. But she is then killed in the most dramatic fashion – beheaded in one strike of a samurai sword by Jiro’s general. The scene, where we witness a splatter of blood sprayed across the wall and not the decapitation, is one of the most remarkable moments in film history (well, in my eyes anyway). It is not unexpected, but when it happens the power is immense and shocking. When one compares it to the relentless and graphically violent acts shown in productions like Game of Thrones or Vikings these days, it just attests to the ability of Kurosawa to visually communicate his message about violence without overwhelming the viewer.

Kyoami, Hidetora’s jester, is a hugely intriguing character who matters greatly in the story even though he is a minor player. He is portrayed as the traditional fool from medieval times, and although a character like this has no real basis in Japanese history, Kurosawa utilises him to be the orator of Shakespearean riddles, which in effect are the more profound existential statements uttered in the film. The role was played by transvestite and gay comedian Shinnosuke Ikehata, also known as Peter, who brings a sometimes annoying but ultimately heartfelt connection to proceedings. The acting by Peter (and Nakadai and Harada) is straight from the stage, and in particular traditional Noh theatre. Like in earlier Kurosawa films, the influence of Noh is very strong, whether through the acting, the costumes or the themes.

The blind Tsurumaru (Nomura) plays a tune on his flute

The actor Mansai Nomura who plays Tsurumaru, the mysterious blind man, appears to wear a mask during the film, and this would also be a direct reference to the Noh tradition. Tsurumaru, although a minor character like Kyoami, also plays an important role in Kurosawa’s story. He provides shelter and food for the feverish Hidetora even though he becomes aware that this stranger is in fact the ‘Great Lord’ whose army gouged his eyes out in the first place. Tsurumaru is a passive presence amidst all the chaos. He carries around and plays a flute – a symbol of divine love – and is later given a picture of Amitābha (Buddha) – a symbol of ‘immeasurable light and life’.

It is the gods who weep. They see us killing each other over and over since time began. They cannot save us from ourselves.

The concept of war is very prominent in Ran, and it is remarkable how visually and aurally it is treated. The scene of the ambush at Saburo’s castle is a particularly stunning example. After walking out on his other two sons in disgust, Hidetora and his few loyalists find refuge in the castle that was meant for his now exiled son Saburo. Taro and Jiro join forces to besiege the place, mercilessly killing their father’s defenders and forcing him out of the castle as it is burned to the ground. This gripping and violent sequence is spared of any battle noise, and only intermittent orchestral music accompanies the visual horror. There are no screams or yells heard as soldiers are viciously murdered by arquebus bullets, arrows and swords. Blood pours down through the wooden floorboards of the castle, a man holds his own severed arm in a moment of delirium, and Hidetora’s concubines collectively stabs themselves to death so as to evade a more hideous demise. And yet not an actual human sound is uttered. The sequence too evolves into surrealism when Hidetora, purposefully spared of the violence, emerges from the castle like a ghost (white garments and extremely ashen-faced) leaving through the gates in a bewitched state. The music is then broken by an arquebus shot that penetrates through a star in the garment of the watching Taro – he is treacherously killed by Jiro’s general. This moment, realised in the surrounds of strewn bodies, white smoke and volcanic ash, compounds Kurosawa’s apocalyptic vision of political devastation and destruction.

Taro and Jiro’s forces allow a bewitched Hidetora to leave the castle

This castle was custom-built to historical specification by Kurosawa’s crew and it was situated near Mount Fuji in an actual volcanic landscape. The structures of this and the other castles (the actual ancient remains of Himeji-jo and Kumamoto-jo) are accurately and intricately adhered to from historical sources and archaeological evidence. The attention to detail is what makes Kurosawa stand out in the crowd. The level of work that went into the making of costumes for the film was truly astounding too. Apparently 1,400 uniforms, kimonos and armour suits were verified by historians and then hand-made by master tailors from around Japan and it took over two years to make them all. No wonder Emi Wada won the Oscar for Best Costume Design. The soldiers’ uniforms are particularly effective. They make a huge impression on the viewer during the battle scenes. The soldiers rush and race on horseback with variously coloured flags fastened to their backs so that they flap over their helmets, each differentiating the army they are a part of. The impression is great and lasting.

Man is born crying. When he has cried enough, he dies.

Saburo and his generals watch the battle from afar

The cinematography in Ran is often breathtaking. Several unforgettable scenes are set up with powerful imagery, where humans are marked as abstract objects in the foreground of an immense natural background, be it mountains, rivers, trees or sky. Kurosawa had up until then presented most of his masterpieces in black and white (Rashomon, Yojimbo, Seven Samurai, Ikiru) or else did not have the budget to fully engross the viewer with coloured photography (Dersu Uzala, Dodes’ka-den). Here, he employed three photographers, Takao Saito, Masaharu Ueda and Asakazu Nakai, to appropriate his glorified vision of tempestuous events from the past, and they managed this to stunning effect. As his own eyesight was failing him, Kurosawa communicated his vision through story-boarded drawings he had sketched. There are many stand-out examples of beautiful cinematography but the most iconic is the apocalyptic scene of soldiers on horseback crossing a river, flags waving and water vigorously splashing. The accompanying music by composer Toru Takemitsu makes the contingent’s violent movements all the more threatening and nihilistic.

Saburo’s army march through the river

And it is true that Kurosawa’s overall outlook here is nihilistic. In the final scene, Tsurumaru wanders around the ruins of his family’s castle and drops his Buddha portrait over a wall edge, leaving him unsure and disorientated. It is a most downbeat ending. Kurosawa is indicating that although the wars between the ‘Great Lord’ and his sons have ended, everything else is unresolved and peace can easily be tipped over the edge. Man has been killing each other since the beginning of time and the gods just watch on, unwilling to step in. It is almost as if he is saying that hell is on earth, not below it. Indeed by 1985, Kurosawa had seen plenty of hell in his life. The reports that he only stopped filming for one day when his wife of 39 years passed away during the production points to a mind completely entrenched in his work, but also to a man unwilling to allow grief get in the way of his vision. As humanely incomprehensible as that sounds, it sort of adds up when you consider Kurosawa’s career up to that point, particularly his suicide attempts. At 75 years of age, he is beyond dwelling on helplessness and is resigned to his fate. One can see an autobiographical account in the character of Hidetora – at his moment of complete defeat, he tries to commit seppuku but he finds no sword in his scabbard. So instead he carries on his descent into madness.

Man is a genius when he is dreaming.

Of course, there was a silver lining for Kurosawa after Ran was released. It won several awards in Japan and across the world (including a Best Director nomination at the Oscars), and it re-established his position as one of the greats. Kurosawa had reached his pinnacle and was finally earning gushing praise from his peers overseas. There is a retrospective feeling that from 1985 onwards, Kurosawa had found his plateau and was now keen to see out his days embracing the wonder of his potential after-life. His next film Dreams was released in 1990, and it offered us a series of personal vignettes that were supposedly based on actual recurring dreams he had. The film was written and directed by Kurosawa and it received financial heft once again from his admirers abroad: Lucas, Coppola, and Steven Spielberg. Martin Scorsese even shows up in a rare acting role as Vincent van Gogh. Dreams appears to be a deeply personal and, let’s be honest, self-indulgent film that deals with aspects of Kurosawa’s childhood, his beliefs, his creativity and his reflections on his home country as well as the world. Unlike his past films, which often deal in historical narratives, here Kurosawa takes his canvas and throws his paints around. It is slow, mysterious, fragmentary and sometimes hard to grasp. But the mastery of Kurosawa’s creativity is still very much alive, and the picture is so very beautiful to look at.

A snapshot of Akira Kurosawa’s Dreams

He followed up Dreams with two film adaptations: Rhapsody in August in 1991 and Madadayo (or Not Yet) in 1993. Rhapsody in August concerns a family in post-War Japan and their responses to the atomic bombings, while Madadayo centres on a retired language professor and the relationship he has with his former students. Although both were not massively well-received, they signified the aging sentiments of an 80-something Kurosawa. He was wondering aloud about his relevance in a modern Japan, and he was still pitching interesting ideas about our place in this universe. Kurosawa continued to write further screenplays beyond this with the intention to direct them as films, but in 1995 he had an accident that put him in a wheelchair for the rest of his life. In 1998, at the age of 88, he died of a stroke. But right until the end, he was certainly still dreaming. And his legacy and influence thankfully still lives on in the world of cinema.

One thought on “Akira Kurosawa – A Master of Film Part 4: I Ran…in Dreams”