The noughties marked my life’s maturing (ages 14-24) and by way of that, marked the ascendancy of my passion for film. It was during this time that I generally started to reject the mainstream and seek out more independent material. Whether because I was genuinely establishing my taste in art or because I just wanted to be cool and accepted, I am not sure. Probably both. Being serious and pretentious can go hand and hand when you are somewhat of an introvert. But this was the path I took, loving and hating things I saw on the screen, studying them, trying to understand them, and eventually writing about them. The journey was an interesting one when I look back – from watching the LOL comedy of 2000, Meet the Parents, at the local mobile cinema with my family, to attending an Irish Film Institute screening of Austrian filmmaker Michael Haneke’s dark historical drama The White Ribbon in 2009. And so much more in-between (let me be clear though: even though Haneke’s film is a masterpiece, I would probably re-watch Meet the Parents if given the choice nowadays!)

The small screen was a massive influence on me around the turn of the millennium – it was just that bit more accessible for a rural farm family – and with The Sopranos, a thoroughly adult TV drama, there was a major bench-marker in terms of quality during my couch-dwelling mid-teen life (nothing really compares to that show for me, even The Wire!) It certainly set the tone in early-2000s popular culture, and arguably spurred a major improvement in Big Screen, mature-age drama globally. This, of course, was a time when the US imposed itself on the world in even greater gregarious measures after the terrorist attacks on the Twin Towers on the 11th of September, 2001. Everything seemed to change after that moment, such was the visual impact of the videos that captured it (re-watching Paul Greengrass’s superb United 93 recently prompted a profound, emotional outburst that brought me back there). It does seem that Hollywood/American cinema took a different tack after 9/11 (certainly it was better than the dross regularly dragged out in the nineties), and the rest of the world did appear to get closer all of a sudden.

Sofia Coppola had the future superstar Scarlett Johansson explore Japan in her delectable mood-piece Lost in Translation, and she followed this with an intriguing and often overlooked ‘Americanised’ take on the famous French royal in Marie Antoinette. Wes Anderson locked in his quirky, extraordinary attention-to-detail filmmaking technique beginning with The Royal Tenenbaums and The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou at the start of the decade – an approach that indeed had its roots in European arthouse cinema of yesteryear. The relative success of these ‘indie’ films point to a more attentive audience, an audience that takes in more than just the ‘red/white stripes and blue with the stars’. In fact, non-English language films enjoyed much success in the US throughout the 2000s – Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000) and Hero (2002) were massive hits from part-Asian productions; Amélie (2001) coming out of France stole the hearts of everybody; Battle Royale from Japan (2000) established itself alongside the best in extreme cult cinema and influenced Tarantino’s forthcoming Kill Bill double bill in 2003 and 2004; and a resounding explosion of Mexican talent came to the fore in the form of ‘The Three Amigos’: Alfonso Cuarón (Y tu mamá también), Alejandro González Iñárritu (Amores perros) and Guillermo del Toro (Pan’s Labyrinth), all of whom would go on to make Hollywood movies and win Oscars.

The decade did see a continuing indulgence of big blockbusters, which cost lots of money and made lots of more money – from Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone in 2001 to James Cameron’s Avatar in 2009. In between, you had The Lord of the Rings trilogy, a further five Harry Potter films, two more Star Wars prequels, three Pirates of the Caribbean films, and a couple of The Chronicles of Narnia adaptations. The fantasy was laid on thick and fast, and the non-fantasy enthusiasts among us are still having to put up with that out-of-control craze even now! Those blasted advancements in CGI technology (developed out of the rise of video game popularity in the previous decades) led to this of course. I think it is no surprise that The Matrix sequels, disappointing over-reaches that they were, were caught up in the period when other CGI-heavy franchises were sweeping profits at the box-office – the original had marked some incredible, ground-breaking effects on-screen, but what followed were hollow, silly visuals accompanied by crappy storylines. By the end of the decade, Marvel and the superhero farce was beginning to take hold, and a ‘cinematic universe’ was forming (sigh). At least before all that, we had the deeply satisfying Batman Begins and The Dark Knight, which were down to the visionary genius of Christopher Nolan, who had also given us the excellent Memento at the start of the decade.

But nodding more towards quality, here are the five films from the first decade of the second millennium that were included in the latest Sight and Sound critics’ list of the Greatest Films of All Time Top 100:

- Tropical Malady (2004, Apichatpong Weerasethakul) (=95)

- Spirited Away (2001, Hayou Miyazaki) (=75)

- The Gleaners and I (2000, Agnès Varda) (=67)

- Mulholland Dr. (2001, David Lynch) (8)

- In the Mood for Love (2000, Wong Kar Wai) (5)

Except for Tropical Malady, which I have not yet seen, in the words of Meg Ryan from When Harry Met Sally: ‘yes, yes, yes…and yes’. Spirited Away is a fantastical extravaganza of animated genius. The Gleaners and I is a remarkable documentary around the practice of gleaning from the irrepressible Ms Varda. Mulholland Dr. is one of the most mesmerising cryptic-tales ever committed to celluloid and as weird as it is, it is very re-watchable. And In the Mood for Love offers decadent, hypnotic cinematography, with a deeply emotive story that takes hold of your soul.

The following crème-de-la-crème from the noughties did not make the list, but are worth a mention: Darren Aronofsky’s harrowing anti-drug masterpiece, Requiem for a Dream; Michael Mann’s strange but intoxicating thriller, Collateral; a sweet and beautiful rural New Jersey-set, Peter Dinklage-starring comedy, The Station Agent; Fernando Meirelles’ slick, pulsating Brazilian crime film City of God; Daniel Day Lewis in Paul Thomas Anderson’s singular, magnum opus There Will Be Blood; the wine-roadtrip comic classic, Sideways; the magnificent Duncan Jones sci-fi debut, Moon; the Swedish comedic gem, Tillsammans; the Swedish horror gem, Let the Right One In; from Korea, the thrilling, disturbing and wholly masterful Oldboy; from Israel, a deep rumination on the Lebanon War in animated format, Waltz with Bashir; a stunning raw portrait of a young African American woman in modern-day New York, Precious; and two films that are not easily forgotten after you watch them, Michael Haneke’s Cache/Hidden, and Shane Meadows’ Dead Man’s Shoes.

Add to that my own firm five favourites from the decade:

Ali Zaoua, Prince of the Streets (2000, Nabil Ayouch)

Youth, crime, and the city streets. A concoction that seems irresistible to filmmakers across time. Luis Buñuel tackled it as far back as 1950 with his social-realist masterwork Los Olvidados/The Young and the Damned. 50 years later, director Nabil Ayouch takes inspiration from Buñuel’s treatment, substitutes Mexico City for Casablanca, surrealism for magical realism, and brings the story into a more modern setting with even harder-hitting thrusts. Ayouch, born in Paris but of Moroccan origin and living most of his life in Casablanca, was acutely aware of the growing divide between rich and poor and the realities of city poverty when he embarked upon the script for Ali Zaoua. His story focuses on a quartet of young teenage boys, helplessly impoverished, hardened by the streets, addicted to glue-sniffing, and involved in petty crime. The situation is dire and doesn’t get much better as the film unfolds. However, as shattering as the subject matter appears, there is a master-stroke to Ayouch’s weaving of a fantasy adjacent to the awful mess of reality.

The titular Ali seeks an alternative life situated upon the seas, where he happily controls a ship, and two alternating setting suns keep the day alive forever. These scenes within Ali’s mind counteract the bleakness of his everyday life, visually and poetically. His single mother is a sex worker trying to give her son a future. A brutal, sexually abusive gang leader rules the streets. The authorities don’t care. And in a world where life is cheap (or ‘a pile of shit’), death lingers around every corner, as is the tragic fate that befalls Ali very early on. In many ways, Ali and his nautical fantasy becomes the spiritual guide and determination for his friends, as they seek to defy and overcome the odds in order to somewhat fulfill what their fallen comrade (the ‘Prince’) could never have reasonably achieved in his lifetime. It is a story of heartbreak, but is also a story full of tenderness and humour, and given that the characters are mostly portrayed by non-actors, it is quite an extraordinary achievement.

Memories of Murder (2003, Bong Joon-ho)

It is a wonder how it took 19 years and 5 films for Bong Joon-ho to be fully recognised around the world as a top-class filmmaker. The Host and Snowpiercer brought some worldwide success due to their action-oriented appeal, but it was only until Parasite in 2019 that acclaim for his superb screenwriting and directing skills came to the fore. Before all that, he made an independent gem in Barking Dogs Never Bite (2000), and followed it up three years later with the utterly astonishing true crime film, Memories of Murder.

Set in the rural South Korean city of Hwaseong in the late 1980s, the film follows the investigations into a series of related rapes and murders. But this ain’t The Silence of the Lambs. There is no Buffalo Bill or Hannibal Lector. Nor is there a competent detective like Clarice Starling. Instead, we have two buffoon detectives (played by Song Kang-ho and Kim Roi-ha), who are later joined by a young volunteer forensic specialist from Seoul (Kim Sang-kyung), who is not much better. The film begins and carries on like a screwball comedy, but slowly and surely, the grisly nature of the crimes and the body-count starts to overcome. The seriousness of a seemingly unstoppable situation sits uneasily with the viewer. Even more profound it becomes, when one understands that with this film, Bong was defrosting an actual unresolved cold case that took place during Chun Doo-hwan’s autocratic and oppressive rule of the country*.

Bong’s retelling, albeit in entertaining movie format, has much to say about the powerlessness experienced by Korean citizens back then, and it explores how incompetent governance and unchecked masculinity was a contributing factor to the slaughter of innocent young women. There is a genius to Bong’s filmmaking approach, and this is exemplified by an outstanding commitment in his mainstay lead-man Song Kang-ho. The film is at times frantic, messy, infuriating, hilarious and traumatic, but always it is grounded in challenging realism. The final scene, where years later Song’s now retired detective, peers down the culvert where the first victim had been found, and stares into the camera as if finding the killer sitting amongst us in the audience, is chilling to the bone.

*one should note that a man confessed to the murders many years after the film was made.

The Lives of Others (2006, Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck)

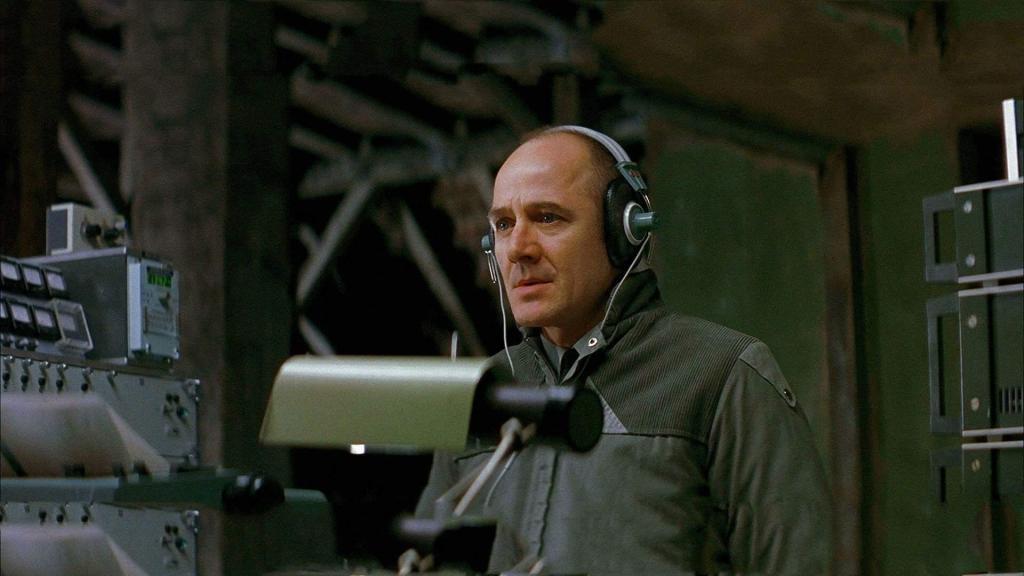

Although the question of authenticity has been thrown at von Donnersmarck (almost inevitable when a film bases itself around events that occurred in reality), his most magnificent film here manages to achieve on so many levels. Set in East Berlin in 1984 when the German Democratic Republic’s secret police (the Stasi) actively monitored its own citizens, the film gives us a trio of intertwining characters: one, a diligent Stasi officer (Ulrich Mühe) assigned to tap and listen to potentially disloyal citizens; two, a handsome socialist playwright (Sebastian Koch) who lives a comfortable life; and three, a beautiful female actor (Martina Gedeck) who is having a romantic relationship with the playwright. There is no foul in the playwright and actor’s relationship, but suspicion is what drives the Stasi, and once a Government Minister covets the woman for himself, there is only one outcome that the officer must attain.

This is the type of ‘love triangle’ story that has been offered through film several times before, but when it comes to a drama set in East Germany prior to the Fall of the Berlin Wall, we are in unique territory. There is also a quiet power to the story, as tragic as it is, and at no point is the judgement laid on thick. Mühe plays the Stasi officer with cautious empathy – a man brainwashed by his Government’s warped idea of civility and terrified to go against it, but still fascinated by the humanity he encounters when eavesdropping on others. I knew very little about East Germany and the Stasi until I saw this film (probably not alone there), and as enraging as it is to know that this level of Big Brother control and terror took place not that long ago (it still goes on subtly and nefariously everywhere), I think von Donnersmarck makes the point that eventually good will win out because in the end, actions of idiocy will fail – signified with the events of 1989 when the people of East Germany themselves took back the power as shown at the end of the film.

This Is England (2006, Shane Meadows)

A permeating, unhinged, masculine aggression is magnificently offset by intelligent, tender moments between strong young characters (both male and female, but with hints of non-binary too), and this is what places Shane Meadows’ astounding This Is England as one of the greatest British movies ever made in my opinion. It takes Alan Clarke’s ‘these people are despicable’ approach to gritty realism and turns it on its head by digging down into that despicable-ness and offering some interesting, more empathetic perspectives.

It is 1983 on the north-east coast of England, and a 12-year-old kid is struggling to fit in having lost his father to the Falklands War. He is dressed in bell bottoms by his loving mother, and is bullied as a result. His life is transformed when he falls in with a gang of skinheads – unbeknownst to me at the time, and indeed a motivation to set the record straight by Meadows with the making of this film, skinheads were not strictly a far-right, neo-Nazi thing. The gang, equally made up of young women and men (one of them being African Caribbean), have a certain style: Dr. Martens, Ben Sherman/Fred Perry shirts, fully or partially shaved heads etc. They take in the young kid and treat him as if he was one of their family. And all is fine and well until the ‘beast of the piece’ arrives in the form of a charming but clearly psychopathic Pitbull named Combo, who has designs on driving the gang towards far-right, racist violence.

Given that this is somewhat auto-biographical for Meadows, his command of proceedings is formidable – the bleak urban setting of Grimsby, the sense of early eighties Thatcherite societal decay, the melding of mod, new-romantic and post-punk subcultures, and the often angry, youthful search for an identity. As well, the soundtrack of ska and reggae gems (Toots & The Maytals, The Specials) is awesome. The performances, not least by Thomas Turgoose as the 12-year-old lead and Stephen Graham as Combo, are deftly executed with honesty and raw, natural emotion. This all positions the film, I think, in a special place. You get the feeling that a beautiful, collective experience occurred with the cast and crew during filming – indicated by the follow-up of three critically acclaimed TV sequel series.

Wendy and Lucy (2008, Kelly Reichardt)

I have waxed lyrical about Kelly Reichardt’s filmmaking before, and out of all the brilliant films she continues to create, it is Wendy and Lucy that tops my personal list. Here lies a short, minimalist, perfect film. Wendy is a struggling young woman, seemingly an economic refugee in her own country, driving her way north from Indiana with her beautiful golden-coloured dog, Lucy, in search of work that supposedly pays well on the coast of Alaska. No doubt she is running away from her own troubles, but in typical Reichardt fashion, there are no queue cards for her life’s story up until now. In fact, there is sparse enough dialogue for us to understand any of the story. We just float along with Wendy and Lucy as they wander the Pacific Northwest, complimented by wistful sounds of nature, the road, the trains, the gentle hustle of a small country Oregon town. If you listen closely, you may hear their own thoughts!

The feelings experienced by the viewer are ones of calm and melancholy. Wendy, portrayed beautifully by Michelle Williams, is a partial purveyor of her own simplified and unfortunate descent. She is a wandering lost soul, at once helpless and vulnerable, but then at other times she is determined, self-effacing and resilient. She makes mistakes, she makes sacrifices, she tries to succeed in her journey by carefully calculating her plan and her pennies in her notebook, but then takes her eye off her dog and loses her car. The people she meets are not like those seen in Into the Wild (another Alaskan journey film released around the same time). They are not figments of the author’s imagination. They are real people who often react to Wendy’s situation with indifference, sometimes showing compassion, sometimes not. All of this forces a difficult path for her, and for the viewer. But Reichardt never seeks to trick us, she always offers a neutral perspective. It is up to us to follow Wendy’s path and find the hope and positivity where it can be found. It is there, of course, if we look close enough. At the end of the day, Wendy and Lucy is a film about everything, but appears to be about nothing.