‘I like cooking up extra ideas to add to the sets and costumes, and inventing an imaginary world. But what I’m more inspired by is something that happened to me or someone in my life who had a strong effect on me, or a novel, short story, play, or a movie where the characters moved me, or where I was swept up in it.’

Wes Anderson

Wes Anderson has now made nine films. He’s not even 50 years old. He made his first feature film when he was 25 (re-making a short film he had directed a few years earlier). By 2018, he has arguably become the most influential contemporary director of our times. And with good reason. Anderson not only brings a wonderful whimsical flavour to modern film-making, he has also carved out a completely original niche in visual art. His latest film, Isle of Dogs, is only the most recent example to demonstrate this.

I first became acquainted with the ‘World of Wes’ when I watched The Royal Tenenbaums while attending university c. 2003. Of course, by then he had already become an established indie talent after the success of Rushmore in 1998 and this film in 2001. Tenenbaums struck a chord with me back then because it offered an understanding of life, love and death through a scope of exciting creativity. It was fresh, unique, and all contained within a place that your mind could escape to. The Royal Tenenbaums captured so much for me at that age and even with a repeated viewing 15 years later, it still makes perfect sense as to why I like it so much. It is funny and serious, sad and happy, cool and offbeat, wonderfully directed and superbly acted. It was also different beyond anything I had ever seen prior to that – I guess I thought I was being an adult for the first time by saying that ‘I got’ what was being portrayed on screen (it really had little reflection on my own life). But since then, I have seen his two prior films (Bottle Rocket and Rushmore) and his six subsequent films (The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou, The Darjeeling Limited, Fantastic Mr. Fox, Moonrise Kingdom, The Grand Budapest Hotel and Isle of Dogs) and they have all, without exception, been equally joyous to watch.

The uniqueness of a Wes Anderson film is hard to describe in a few sentences (thus, this blog post). When you watch one of his films, you are transported and immersed into something very special. Of course, there is so much similar material out there now – his movies have come to influence so much in modern film, and indeed in modern pop culture. The films of Richard Ayoade and Noah Baumbach, and so many US indie comedies that are released these days have hallmarks of Anderson’s art. His films ultimately have a positive outlook about life and humanity, and the boundless imagination that exists at their core are inevitably a good thing. You can call it ‘geek chic’ all you want but that doesn’t diminish its resonance and importance to the current zeitgeist!

But what makes an Anderson film special? What is it that makes him stand out as a unique director?

***************************

The Family Connection

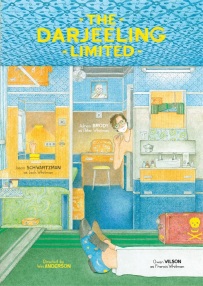

Anderson’s brother, Eric is the skilled artist of the family apparently. He contributed the artistic backgrounds and design ideas for The Royal Tenenbaums and his artwork can be seen on the DVD and Blu-ray packaging for most of his brother’s films (see image above). He even provided the voice for Kristofferson, the visiting relative in Fantastic Mr. Fox. Many of the themes in Anderson’s films are familial related. In some way or another they hark back to his middle-class upbringing in Houston, Texas, and in particular his parents’ divorce when he was just eight. Both brothers have spoken many times about how their father and mother and their respective associated work have been placed in some small way into their art. Their father worked around the world in advertising, while their mother was in real estate and also worked as an archaeologist (Angelica Huston plays an urban archaeologist in her role as the matriarch in The Royal Tenenbaums, while Bill Murray as Steve Zissou in The Life Aquatic carries around a lot of badges, something their father used to do a lot when they were younger).

There is a common thread of familial problems and sibling rivalry in Anderson’s films and this is borne from more than just the Anderson household – the three Wilson brothers (Luke, Owen and Andrew) acted together in his first three films, and Owen co-wrote the screenplays for all of them. Jason Schwartzman (son of Talia Shire) and Roman Coppola (son of Francis Ford), both cousins and from very talented families, have also worked together with Anderson on the scripts for The Darjeeling Limited and Isle of Dogs. As an example, the dysfunction of a family is at the very heart of The Royal Tenenbaums. Gene Hackman’s Royal, after going broke, attempts to reconcile with his estranged family (his wife, his two sons and his adopted daughter), despite having never gave a damn about them before. The kids are all extremely talented and have vied for their parent’s approval when growing up. Dysfunction takes on a different but related form in The Life Aquatic, as Ned Plimpton (Owen Wilson) lands an unexpected bombshell on Steve Zissou’s (Bill Murray) fragile ego by saying he thinks he is his son. In fact, Zissou’s mission to find the Jaguar Shark in the film is played out in a series of disputes and tension among his crew, or in other words, his own dysfunctional family.

The Darjeeling Limited is about three brothers (Jason Schwartzman, Owen Wilson and Adrien Brody) and their reunion/enlightenment journey across India together – the large quantity of suitcases that they bring with them is a metaphor for the personal and family baggage that they continue to hold on to. Anderson’s stop-motion adaptation of Roald Dahl’s Fantastic Mr. Fox also alludes to the family. His film interestingly (and anthropomorphically) delves into the troubled relationships between Mr. Fox, his wife and his son, something that the novella never really attempted to do. In fact it is a very prominent part of the film and makes the content more heartfelt and meaningful.

Some have labelled Anderson’s work shallow because it never delves deep enough into the issues it presents. I tend to disagree. There are many sequences in his films that deal with deep and dark issues on a very profound level: e.g. the genuine depression that befalls teenager Max in Rushmore (related to his mother’s death), Richie’s suicide attempt in The Royal Tenenbaums (related to his love for his step-sister), the tragic death of Ned, and Zissou’s subsequent grief for his supposed son in The Life Aquatic, or the drowning of a young Indian boy in The Darjeeling Limited. Anderson does not treat these more serious moments as the central focus of his films, but he does manage them sensitively enough so that the viewer can reflect upon the characters humanely and with empathy, and hopefully establish a more rounded observation beyond the quirks and the comedy.

Neat and Quirky Art Direction

Anderson has always had a craving for setting up a scene in a visually neat way. Whether he harbours a condition akin to Obsessive Compulsive Disorder or not I don’t know. But what does it matter if the scenes he creates are aesthetically pleasing? Anderson carefully crafts a scene perhaps not to compliment the plot or storyline but rather to make the repeated watching experience more entertaining. Right from the get-go in his modestly budgeted debut, Bottle Rocket, he hinted at developing a particular style of symmetrical composition. The two main characters (played by Luke and Owen Wilson) are often shown close-up and centre-screen. The process becomes more obvious in his later films, particularly in Fantastic Mr. Fox, Moonrise Kingdom and Isle of Dogs, where there are numerous scenes (as shown here) of characters directly at the centre or moving to the centre of the screen with objects, props or other characters neatly placed or coming into shot on either side. Sometimes the camera rapidly moves 90° from one centrally placed character to another, breaking from one carefully composed set to another. The break-away sequence in Fantastic Mr. Fox where the devious farming practices of Boggis, Bunce and Bean are colourfully described by Badger is a superb example of Anderson’s desire to use rapid-fire camera movements with attentively-placed objects around centrally-placed characters.

The attention to detail is something that is worthy of further discussion too. Not only in regards to symmetry but also with set design and colour co-ordination. The Grand Budapest Hotel, which won many awards for its production design, is the supreme example. Before filming, Anderson and his crew went around Europe looking for a large, old building that would ideally fit his vision for the hotel. They found an unused department store in Germany which had been built prior to World War II and magically transformed it into a lively 1930s-style hotel (also changing its façade to reflect the same hotel in the 1960s in a later segment). The end result was a gloriously lavish and authentic-looking set. As we follow events in the hotel, the magnificence of the building looms in the background like its own character. Anderson also utilised Steve Zissou’s research boat, the Belafonte, as an extra character in The Life Aquatic – equally impressive for its design and its presence. We are even treated to a fourth-wall breakdown where Zissou humorously narrates a visual tour of the boat going from cabin to cabin.

Mention should also be made of Anderson’s devotion to costume design. The ludicrous but funky-looking sea-coloured uniforms (with red beanie) and diving suits of Team Zissou in The Life Aquatic may have been somewhat inspired by the fashions of Jacques Cousteau but they do breathe their own originality – what is most impressive is that they follow the colour schema of the entire film (the colours of the boat, the hot-air balloon, the tiles in the sauna etc.) Then there’s the John McEnroe-inspired tennis outfits of Richie Tenenbaum, the matching grey suits of the three brothers in The Darjeeling Limited, the foxes’ masks as they steal chickens in Fantastic Mr. Fox, the large red duffel coat of narrator Bob Balaban in Moonrise Kingdom, or even Max Fisher’s red beret, large-rimmed glasses and badged blazer in Rushmore. Anderson’s recent film, Isle of Dogs, had a series of distinctive fashion styles floating around too – from the young Japanese boy with a black stripe under one of his eyes to a white American exchange student with a blonde afro.

A Unique Comic Flair

The comedy in Anderson’s movies have certainly evolved since his debut feature. But this is not to say Bottle Rocket didn’t provide any laughs. It remains an underrated film, and in fact boasts a neat, smart script with an authentic crime caper feel. The nods toward humour simmer under the surface, particularly in the clownish character of Dignan (Owen Wilson) and his frequent impatience shown towards his crime acquaintance Bob (Bob Mappelthorpe). With Rushmore, The Royal Tenenbaums and The Life Aquatic, moments of hilarity are more commonplace and are often magnificent. One of my favourite comedic scenes appears in The Royal Tenenbaums when Royal is finally found to be telling lies about his cancer and is then kicked out of the house by the family. His sidekick Pagoda (played by the glorious Kumar Pallana) upset at having been tarnished by his lies, calmly walks over to the crestfallen Royal, takes out a tiny penknife and stabs him. Royal stumbles and with Pagoda now helping him up, shouts at him ‘god damn, that’s the last time you put a knife in me, you hear me?’ Pagoda then proceeds to help him into a taxi. In The Life Aquatic, a most memorable moment comes when Zissou draws a line asking his crew to cross it if they are not willing to stay committed to the mission. Mishearing this, Klaus, the first mate and the most committed to Zissou’s cause (played by Willem Dafoe), crosses it with chest out and looking proud, much to the disappointment of Zissou. It’s pure comedy gold!

The combination of Anderson’s casting and characterisations has now grown into a bit of an institution. While there is clearly an established set-list of regulars that feature in his films (Owen Wilson, Bill Murray, Angelica Huston and Jason Schwartzman), it must now be top of any cultured actor’s wish-list to be asked to be involved in an Anderson project. He has impressively managed to garner comic performances from otherwise straight-laced actors such as Gene Hackman, Harvey Keitel, Michael Gambon, Edward Norton, Bruce Willis, James Caan and F. Murray Abraham. The performance of Ralph Fiennes as the tireless and quick-witted concierge in The Grand Budapest Hotel must come in for special mention though. Whereas the performances of Bill Murray and his delivery of deadpan lines in Rushmore, The Royal Tenenbaums, The Life Aquatic and as the badger in Fantastic Mr. Fox may justifiably receive the fair share of plaudits for comedy (Anderson is credited as giving him his ‘second career’), Fiennes’ Monsieur Gustave is without doubt the greatest comic creation by Anderson. Here, there is solid comedy from an actor not renowned for his humorous roles. The dialogue afforded to him from Anderson’s screenplay is deadly sharp, deliciously camp and filled with a wholesome but reactive realism. My favourite line is delivered when he stands over the deceased Madame Celine (Tilda Swinton), an elderly lady he has been intimate with: “You’re looking so well, darling, you really are… they’ve done a marvelous job. I don’t know what sort of cream they’ve put on you down at the morgue, but I want some.”

The recent Anderson masterwork, Isle of Dogs, played out with plenty of comedy that was as much pleasing as it was ingenious. Having fully realised his ability in stop-motion animation with Fantastic Mr. Fox, Anderson established an elaborate idea about sick dogs in a dystopian Japan after seeing a sign in England for the actual ‘Isle of Dogs’. The imagination that expanded around this is nothing short of awesome, and despite what some people have alleged, the film celebrates Japanese culture as much as it pokes fun at it. The various dog characters all have their exaggerated quips and things to bear – Jeff Goldblum’s Duke steals the show with his penchant for hearing rumours within the dog-world. F. Murray Abraham and Tilda Swinton in their double voice act as the mercurial Jupiter and Oracle are fantastic too – Oracle dazzles all the other dogs with her knowledge, even though it is just because she watches TV. One could argue that in taking the handmade miniatures route, Anderson is able to better demonstrate his propensity for a comic visual style than he would in a live-action feature. But we will see what his next film brings.

A Marvellous Taste in Music

The affinity between certain scenes and music has played a pivotal role in how Anderson’s films are perceived. He has a brilliant knack for marrying music and action together. In Bottle Rocket, he resurrected that wonderful gem from 1968 by Love called ‘Alone Again Or’, which plays while Anthony (Luke Wilson) realises his love for a Paraguayan motel cleaner. In Rushmore, the soundtrack has become as famous as the film itself – the use of Creation’s ‘Making Time’ in the opening, Cat Stevens’ ‘The Wind’ as Max flies a kite with tears in his eyes, or The Rolling Stones’ ‘I am Waiting’ at the beginning of the ‘November’ sequence. In The Royal Tenenbaums you cannot overlook The Mutato Muzika Orchestra’s instrumental version of ‘Hey Jude’ as it plays during the opening moments. Or possibly the scene when Richie waits for Margot at the bus station to the strains of Nico’s hair-standing masterpiece ‘These Days’. The Life Aquatic has its fantastic musical moments too – ‘Gut Feeling’ by Devo, ‘Search and Destroy’ by The Stooges, ‘The Way I Feel Inside’ by The Zombies and ‘Queen Bitch’ by David Bowie to play us out. The soundtrack to The Darjeeling Limited isn’t too shabby either – the beginning is magnificently marked by a cameo of Bill Murray running for, and failing to, catch the train. As he starts to slow, Adrien Brody passes him in shot and The Kinks ‘This Time Tomorrow’ starts to play as the action slows down. It’s a magnificent scene as it marks the break from Murray as a main character from Anderson’s earlier movies and the entrance of a new star in Brody.

It is not just songs from the 1960s and 1970s that makes Anderson’s films tick. He also effectively utilises the talents of composers to provide stirring and trademark scores. Since Darjeeling, Anderson has started to collaborate with the current ‘composer du jour’, Alexandre Desplat, who for Moonrise Kingdom provided this gem of orchestral magic that marks the closing credits (it’s narrated by Jared Gilman, the young star of the film). He subsequently won an Oscar for Best Original Score with The Grand Budapest Hotel, which was inspired by Russian folk instruments and songs. Anderson had previously worked with Mark Mothersbaugh (of Devo) who provided funkier and more electronic-driven scores – the Ping Island sequence in The Life Aquatic being my highlight. Let’s also not forget the brilliant side project by Brazilain artist Seu Jorge in the same film where he covers David Bowie songs in Portuguese (Jorge also played a charterer in that film). Utterly awesome!

***************************

The ‘World of Wes’ (or American Empirical Pictures to be more precise) offers us something very special, be it through slow-motion walking shots, a certain font he uses for a sign on a building, the way he frames his stories with a narrator, a prologue and an epilogue, or a montage flashback with a soundtrack of some awesome song. He offers us contained worlds that are high-end but fully realised dreams with fascinating characters. His love of space and his intent to make it interesting for the viewer is what allows his films to stand out. The structure of his set-pieces can be breath-taking. Filling the screen not only with colour and liveliness, he adds painstaking and imaginative details to each and every part of a shot. It makes his films endlessly watchable over and over again. I think it is safe to say that his attention to detail rivals the likes of Stanley Kubrick (the carefully composed shots in 2001 and The Shining come to mind) and even Akira Kurosawa (a director he pays homage to in Isle of Dogs). The art of Anderson is something I can never tire of – it jumps out and takes you in and you always have fun along the way.

3 thoughts on “Appraising the Art of Anderson. Wesley Wales Anderson”