As mentioned in Part 1, Quentin Tarantino takes us on an entertaining journey through the New Hollywood era of filmmaking in his latest book, Cinema Speculation. Unsurprisingly, he focuses on his favourite directors – all tough and macho like Don Siegel and John Flynn – but he does offer an interesting critique of their works. I like the fact that he often describes the audiences he experienced watching these films with at the time. But he also breaks down some of what the prominent film critics wrote about the films also. Given his own standing as a behemoth Hollywood figure for the past 30 years, he also enjoys access to the directors (and writers) themselves, and indeed, we hear first-hand accounts from the likes of Paul Schrader, Walter Hill, John Milius and John Flynn, which makes this material even more engrossing.

Like I said before, I enjoy Tarantino’s writings, and there are some good insights to be found. His movie-going teen years involved him hanging out for a time with a sort of father-figure, an African American man, who was one of his mother’s lovers. He clearly looked up to this man because he was a movie aficionado, and Tarantino recounts going to see movies with him at theatres that were frequented by other African Americans. Their reactions to the films he saw clearly gave him interesting perspectives, and those perspectives were often-times at odds with what the critics would say. I think this makes his book and its content invaluable. Tarantino’s outlooks on race and violence can be questionable, but I certainly find lots to be garnered from his first-hand experiences of important movies from the seventies as they were first released. Several of these are discussed in detail below.

WARNING: Please be aware that the plots of these films are discussed in detail below, and the endings may also be revealed.

*************************

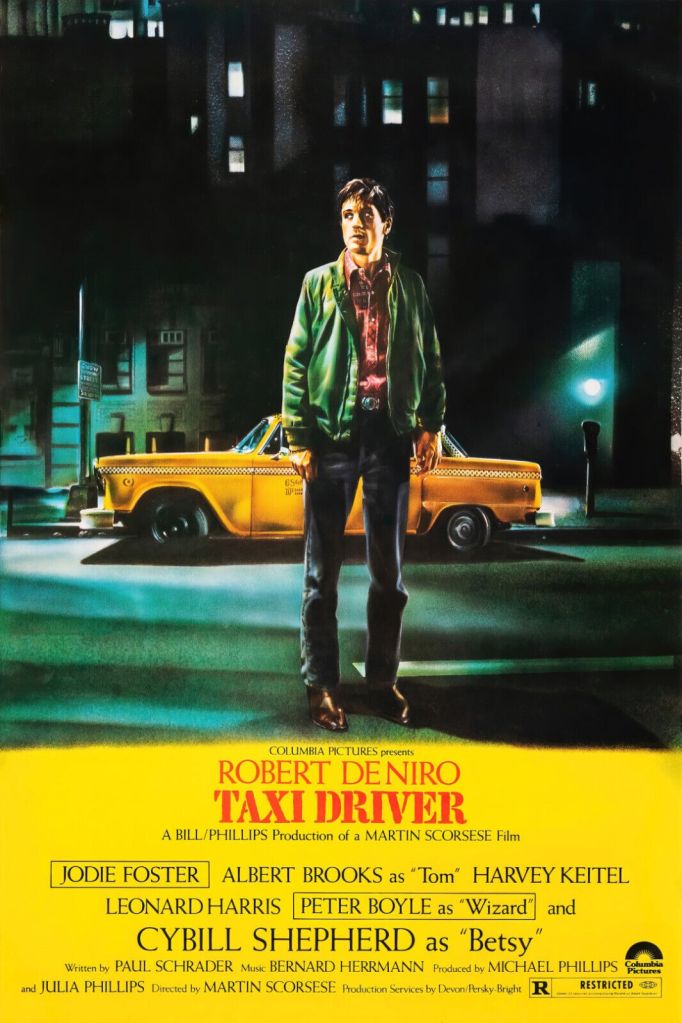

Taxi Driver (1976, Martin Scorsese)

What Tarantino Says:

As many cinephiles may know, Taxi Driver is a reimagining of John Ford’s The Searchers – a young white woman must be saved from perceived barbarous people (Comanches in The Searchers / a paedophile pimp ring in Taxi Driver). Tarantino explains that this was always the intention of Paul Schrader’s story, but whereas Harvey Keitel plays a white pimp in the film, the character was black in the script. It was apparently changed by Scorsese because of the race riots at the time. Tarantino goes to great lengths to explain that ‘the Great White Pimp’ in this and other films from the era was a ‘mythological cinematic creation.’ Even though he contends the myth, he believes that Keitel’s performance in Taxi Driver was magnetic.

He also argues that the film is not racist (despite what critics said) but rather it is a film about a racist – Travis Bickle only sees black men as malevolent criminals. He says the story’s power is in the way it poses the question about Travis to the audience and allows them to make up their own mind. They are drawn into Travis’s world as they watch him act like a ‘goofball,’ and then loses his innocence, often in scary and thrilling ways. Tarantino saw the film first with a black audience and he claims they rooted for Travis because he is up against ‘some really bad guys’ (the paedophile pimps), and the 12-year-old prostitute (played by Jodie Foster) is clearly in need of saving. He also praises the authentic street vibe that Scorsese created, which he believed black audiences could easily relate to. Interestingly, he attacks Scorsese for comments he made long after the film was released regarding the violence at the end. Tarantino reckons Scorsese was disingenuous in distancing himself from the audiences’ apparent thrill from those scenes, because he himself thought they were magnificent, exhilarating and kinetic.

What I Say:

Taxi Driver is a very dark and disturbing film. But I understand that this is exactly what it was meant to be. As Tarantino rightly points out, it is not racist, but it does have a lead character who is a racist. The story of an idiot with extremely dangerous intent makes this film a very potent commentary on contemporary American society (no surprise that Joker, with its Trumpian vibes, was a Taxi Driver rip-off). But I also get why there was a controversy over Taxi Driver – it subverts the idea of the hero. To be honest, every time I watch it, I still don’t know how to feel about Travis – is he worthy of our sympathies and is he to be lauded for his actions, or is it just that the paedophile pimps got their comeuppance and we can rejoice that the 12-year-old girl has been saved? As hard as it all is to digest, you cannot deny the masterful weaving of the story (from Schrader), the engrossing characterisation of Travis (from De Niro), and the cinematic artistry (from Scorsese).

Having said that, the violence at the end is awful. I think Scorsese is deliberately trying to make us question why we may participate in it with such glee even though we are not really on Travis’s side (but we are definitely not on the side of the paedophiles, right?) I certainly did not feel any glee at the end, just confusion because I don’t think the violence is justified. Levels of extreme violence has always been an issue in many of Scorsese’s movies, but I think when he says that he was shocked by audiences getting a thrill from the violent conclusion to Taxi Driver, he reveals an interesting introspection. Whereas Tarantino has an issue with what he said, it makes me like Scorsese as a person even more. It occurs to me that Scorsese never intended for audiences to be celebrating and indulging in the violence, like Tarantino so desperately wants to, but rather requires people to question what the hell is going on in the world today.

*************************

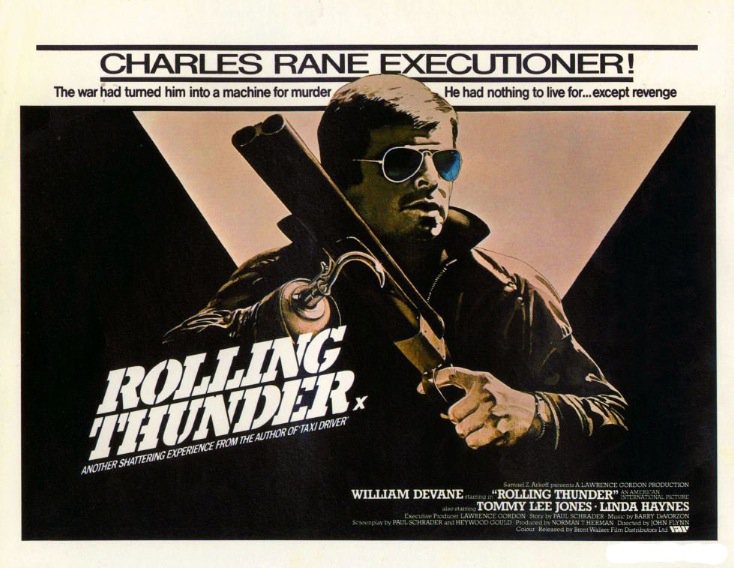

Rolling Thunder (1977, John Flynn)

What Tarantino Says:

Tarantino firmly puts Rolling Thunder ahead of Coming Home in terms of the best films that depict the casualties of the Vietnam War. He finds it to be a deeper, detailed character study, particularly in its first twenty minutes when Major Charles Rane (William Devane) returns to his Texan hometown to a hero’s welcome after spending time as a PoW. He finds his wife and son unable to cope with his presence – they no longer love or want him. The scenes are intense and draws you into the character of Major Rane, as he suffers with PTSD and struggles to connect with anyone. The only two people who Rane finds some connection with are his returning comrade Johnny (Tommy Lee Jones) and an admiring waitress called Linda (Linda Haynes) who falls for Rane. After Rane’s wife and son are murdered, and he loses his hand, in a botched robbery by a Mexican gang, Linda joins him as he crosses the border in his quest for revenge.

The characters of Rane, Johnny (‘I’ll just get my gear’) and Linda all come in for praise by Tarantino, but he is especially enamoured by Linda Haynes ‘perfect’ performance – he describes her dynamic chemistry with Devane as the main reason for the film’s success. He also deems William Devane to be sensational as Rane, arguing that the Rane in Paul Schrader’s script was different to the one Devane portrayed in the film. To Tarantino, Rolling Thunder is the ‘greatest’, most savage and fascist, ‘Revengamatic’ movie ever made. Unsurprisingly, he loves the powerfully-depicted, explicit violence at the end of the film (his passion for John Flynn’s direction is very evident in this part of the book), but he does state that if Flynn was more faithful to Schrader’s script, the movie would have been harder, more cynical and more violent, which he would have preferred.

What I Say:

I do agree that Rolling Thunder is an entertaining watch, and it certainly sat a little better with me than Flynn’s earlier film, The Outfit. But there are some very outdated approaches in the film, e.g. the whole ‘White American = hero, Mexican = villain’ thing. Wiliam Devane as Charlie Rane is something special – he coolly portrays a character that has nothing to lose, a character that has believably had a life experience of unfixable psychological terror (both in war, and at home). It is also kind of cool to see Tommy Lee Jones as a young actor, so obviously showing his potential here. And I agree with Tarantino that Linda Haynes is very good. But let’s be clear, she is very good in the circumstances. I feel like Tarantino only praises the character of Linda because it fulfils the male fantasy i.e. she looks good, she joins in the violence and she does what the man tells her to do. I am in no doubt that Flynn had a misogynistic outlook, and it is painful reading Tarantino’s views on his films, which don’t take this into account.

*************************

Paradise Alley (1978, Sylvester Stallone)

What Tarantino Says:

In the late seventies, Rocky was Tarantino’s favourite movie. He remembers that the film brought a feel-good catharsis to audiences in 1976 after a barrage of tough, gritty, downbeat and cynical films from earlier in the decade. It made a star out of the relatively unknown Sylvester Stallone, who, Tarantino explains, had the screenplay for Paradise Alley in his pocket at the time. This screenplay was nothing like Rocky, but it was even closer to Stallone’s heart than Rocky was, and in the end, the film of this screenplay marked his directorial debut. This is the reason why Tarantino admired Paradise Alley as much as he admired Rocky. It had its detractors, and it was a notable flop upon its release, but Tarantino passionately defends the film to this day.

He describes Paradise Alley as ‘the purest expression of a particular vision’, and notes its timing as being before Stallone’s success with his second directed feature, Rocky II, which catapulted him into super-stardom. He goes on to state that there is a striking realism and believable milieu to Paradise Alley and it demonstrates a writer ‘in love with his own words’. The film’s story is frustrating and messy, but ‘it’s a fucking scream’ according to Tarantino, and he puts this down to Stallone’s wonderful embodiment of Cosmo, the lead character, who is an ‘obnoxious loudmouth’. He also finds some poignant depth in certain characters (such as Vic, Cosmo’s brother) and in certain scenes (the death of Big Glory), and he describes Lazlo Kovacs’ cinematography as eye-popping.

What I Say:

I’m definitely with Tarantino here. I think Paradise Alley is an underrated classic and a hidden gem. I never knew it really existed until I read this entertaining backstory offered by Tarantino. It does surprise me how much of a different person Stallone seemed to be when he was still making his way in Hollywood i.e. pre-macho wanker. Paradise Alley showcases a guy who could write, direct and act really well given the right tools. The photography from Laszlo Kovacs is stunning and there is another top score from Bill Conti (of Rocky fame). Sure, there is a steady dose of corniness to proceedings, but the film is always enjoyable. It has a great array of ethnic New Yorkers (much in the same way as The Sopranos) and who doesn’t like to hear Tom Waits sing and play intriguing background characters?

I do think that the film is more like Rocky than Tarantino claims it to be though. It is another underdog story; it has romance; it is set on the streets; and, instead of boxing it has wrestling as a central plot device/final climax scene. But I just cannot argue that Paradise Alley is better than Rocky, because it ain’t. For one, Rocky has Adrian, who is an evolving, core female character. The women in Paradise Alley, on the other hand, are secondary, and intriguing subplots involving the characters of ‘Bunchie’ and Annie are never really elaborated upon or completed satisfactorily. And then there is the often OTT, cartoonish element to the villains. But that is not to say that Stallone does not create an effective world here. It is an odd, slightly unrealistic envisioning of Manhattan in the 1940s, but it works because, as Tarantino says, it is a pure vision.

*************************

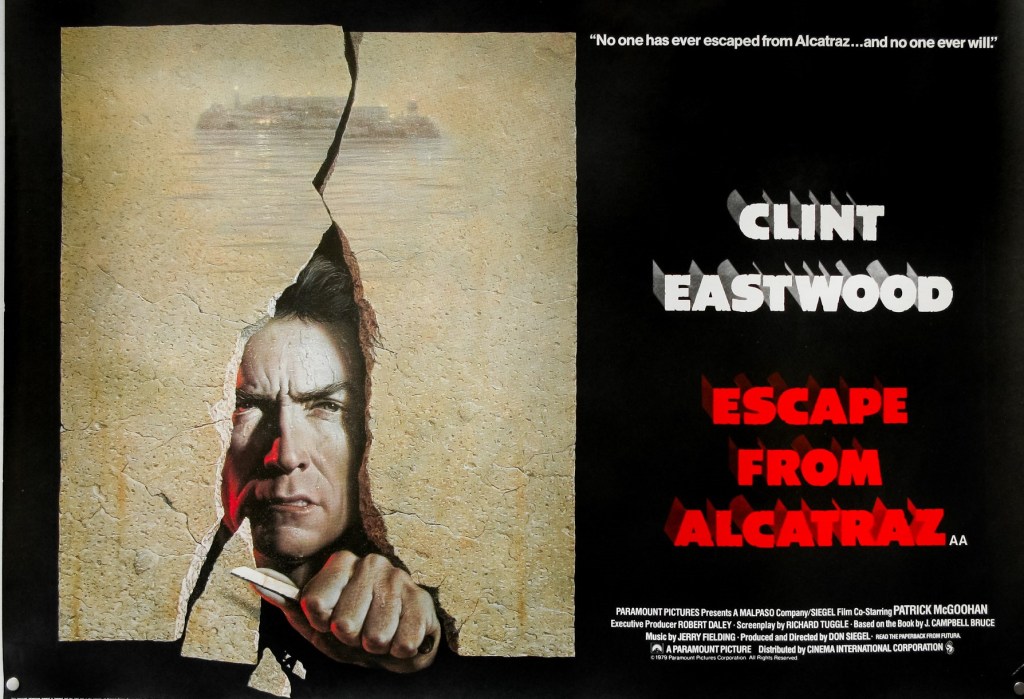

Escape from Alcatraz (1979, Don Siegel)

What Tarantino Says:

Escape to Alcatraz, a prison drama from director Don Siegel and his leading man, Clint Eastwood, proved a revelation for Tarantino when he watched it for a second time when he was older. He describes it as Siegel’s late-in-life masterpiece. It has a stark, period setting, and its story focuses on brutal isolation, monotonous regimented routines, and numbered privileges. The wordless opening sequence, where we are transported back in time, is described by Tarantino as ‘cinematic bravura.’ The expected escape plan in the second half is shown with masterful craft. He praises Siegel’s unique, step-by-step montage approach, and lauds the performance he manages to elicit from mid-career Eastwood. He describes their collaborative partnership as the greatest in the history of cinema, revering their evident mutual respect and ‘masculine’ admiration for one another.

What I Say:

I remember seeing Escape from Alcatraz when I was younger, and glibly dismissed it at the time as a film that my dad would like! That’s a bit unfair on my dad, but what I mean is that it was not exactly aimed at a younger audience. Indeed, the film’s highly acclaimed status overtime has proved that I was destined to return to it in later life, and like Tarantino, re-evaluate it as something special. There is a sparsity of action or even artiness to the film, and at times, you wonder if you are watching a cheaply-made TV movie. But this same sparseness, or starkness as Tarantino describes it, elevates its impact. And I also think that the film would be so much worse-off if it did not have Clint Eastwood at the helm. For once, he gives an understated performance and communicates heroism without forcing it into our faces. There is no doubt that Siegel’s relationship with him allowed this performance to flourish. I agree, Escape from Alcatraz is a masterpiece.

*************************

Hardcore (1979, Paul Schrader)

What Tarantino Says:

Once again, we have a Paul Schrader script (this time a film he also directs) that is another thematic remake of The Searchers. As Tarantino describes, George C. Scott plays a wealthy businessman from Michigan (Jack Van Dorn) who possesses a strong moral fiber, given his puritanical Dutch Calvinist faith. Like Ethan Edwards, he sets out on a quest to retrieve his daughter from the clutches of bad people AKA the Porn Industry in LA! Tarantino gives the film credit for its ‘compelling premise’ and praises the perfect casting of Scott, but its ‘undeniable power’ wanes in the second half and he places all the blame at the foot of Schrader’s lame script. He also criticises Peter Boyle’s ridiculous private detective and Season Hubley’s ‘Niki the prostitute’ who helps Van Dorn track down his daughter.

Tarantino opines that Schrader offers a slanderous view of the Porn Industry in the late seventies, and this is what makes his film a ‘phony-baloney moralistic con-job.’ The plot uses a snuff film as a means to heighten the despicable nature of the porno world beyond just sleaze. As he explains, snuff films were an urban myth used to marginalise the adult film industry at the time. But this is Schrader justifying to the audience why Van Dorn must continue to search for and save his daughter, even though it seems obvious to Tarantino that his daughter chose to come to LA and act in adult films. To him, and to audiences he witnessed in the late seventies, they wished that Van Dorn would just give up and go home. His insistence to stick around is the undoing of the film, and the ending where the daughter is saved, and does go back to Michigan with her father, is deeply contrived and not at all convincing.

What I Say:

I know it was not Schrader’s intent, but I find Hardcore to be an unintentional comical film. Tarantino makes reference to one scene that he says was injected for comical relief: when Van Dorn dresses in disguise as a porn producer and interviews young men for a part. This is quite hilarious because it is so ridiculous, and there are many other similar instances where you just can’t take any of this seriously. Van Dorn is so out of his depth wandering in and out of sex shops and peep shows, looking shocked and perplexed at what he witnesses. Honestly, this could have easily been played as a slapstick comedy. There are times when I feel like Scott (playing Van Dorn) is on the verge of laughing rather than despair.

I guess Tarantino has a point that Schrader failed to assemble all the parts into a cohesive whole. The ‘compelling premise’ of the movie for me is the prevalence of abuse towards women in the adult film industry. Schrader makes an attempt in bringing the problems with the industry into focus, but in the end, there is no real, serious treatment and everything feels hollow and ineffective. I also think that the women in the film are poorly written and condescendingly presented. They are mostly secondary to Van Dorn’s moralistic quest, and that is the biggest tragedy of the film. Tarantino may blame the actresses for poor performances, but what the hell were they supposed to have done? As much as the film decries the Porn Industry, we may well have an unintentional sub-text here about sexism in Hollywood – unsurprisingly Tarantino does not engage on that point!

*************************

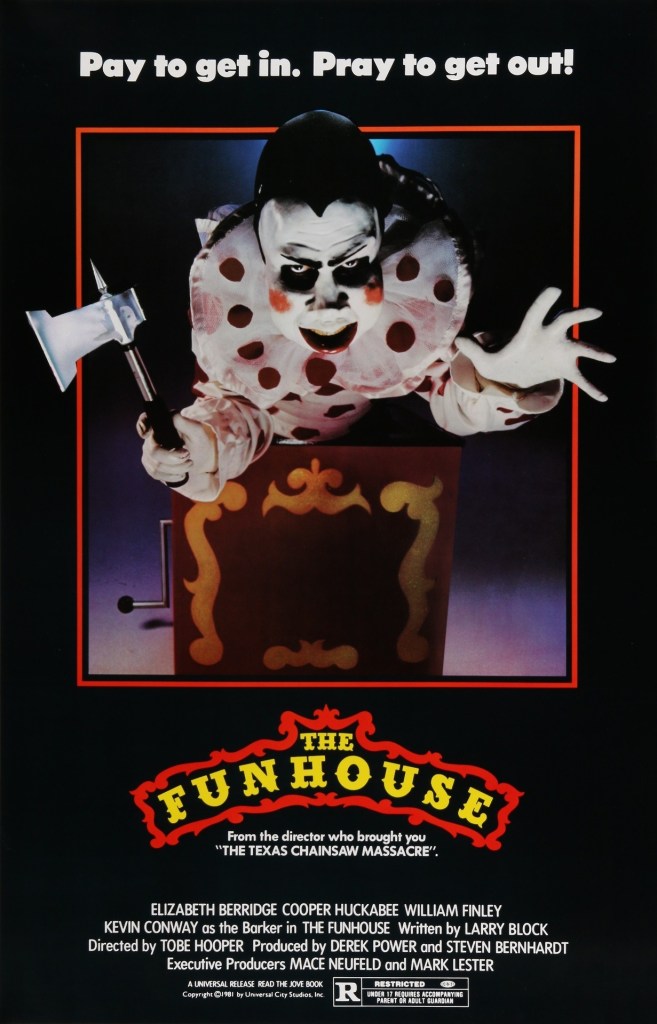

The Funhouse (1981, Tobe Hooper)

What Tarantino Says:

Tarantino found The Funhouse mediocre when he first saw it, but seeing it again in 2011 he was much more impressed by Tobe Hooper’s direction: the staging of scenes; the dynamic coverage; and the cynical, tawdry, and downright nasty tone. He praises the cinematography and the ‘creepy carnival’ production design, but it is the depth and sophistication of Larry Block’s screenplay that stands out. The film came out at the height of the horror movie boom in the early eighties so a lot of tropes and cliches are used, but given Hooper’s background with The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (Tarantino calls it the best movie of all time), it manages to work on different levels.

Tarantino focuses much of his attention on the relationship between the teenage lead, Amy, and her younger brother, Joey. In the first scene, Joey, wearing a mask, goes into his sister’s shower and pretends to stab her, after which she chases him away and tells him he is going to get his comeuppance one day. To Tarantino, it demonstrates a repellent quality in each of the characters immediately – the boy as a creep with a tendency towards sexual violence, and the girl as sadistic and vindictive. In fact, he goes on to say, all of the teenagers in the film are remarkably unappealing, and he praises the young actors for making this so. The only sympathetic character is the grotesque villain of the piece: the birth-defected boy referred to in demeaning terms as ‘The Monster’ in the final credits. However, once the boy removes his Frankenstein mask and we see the true monster (with surprisingly bad make-up), our sympathy is lost. Prior to that, he has a sexual interaction with a phony fortune teller, which according to Tarantino, is the most powerful scene in the film.

What I Say:

I don’t think The Texas Chainsaw Massacre is the best movie of all time. It has its merits, but I find it to be cynical, exploitative nonsense. Tobe Hopper has a history of cynical, exploitative movies and his vision here of annoying teenagers being murdered one-by-one in a crazed carnival is the best example of his deeply problematic worldview. Now, I do agree with Tarantino that there are some aspects of The Funhouse that elevate it above the usual horror movie dross, but we are not talking about ground-breaking movie magic here. Tarantino mentions the effective use of crane shots, but isn’t that what you would expect from an experienced and competent film crew? He also mentions the production design, specifically the crafting of an effectively creepy funfair background. Yeah, it’s okay, but I found it a bit repetitive after a while and the unique sense of place wears off after a while. To be honest, the film comes across as a cheap, run-of-the-mill production, and it looks quite dated now. I think Tarantino’s first impression hit the nail on the head – it is a mediocre movie.

You may be starting to understand that I don’t really care for the slasher genre, defined as it is (and continues to be) by graphic, sadistic and sexualised violence and gratuitous female nudity. The Funhouse may be relatively tame in this regard but it is framed by two scenes that have grim and tasteless vibes: the shower sequence at the start, and the ‘final girl’ sequence as Amy tries to escape from The Monster. The whole thing is derivative drivel really, and I can never understand why an audience would enjoy a never-ending, no-hope, violent pursuit of teenagers. The teenagers do not help themselves, and they contribute to their own downfall with their stupidity, but this is the contrivance of Hooper. Or should I say, the lack of humanity of Hooper. He deliberately stereotypes a whole age group: these kids are only interested in sex, resent their parents, and are not very smart. Maybe perfect for a slasher movie, but sorry mate, you may have fooled Tarantino, but you haven’t fooled me. I won’t be watching this film for a second time.