And we wanna get loaded and we wanna have a good time

Dialogue from Roger Corman’s 1960s counterculture classic The Wild Angels was an interesting choice for the opening of Primal Scream’s ‘Loaded’, a seminal indie-dance anthem released in February 1990, but it did resonate with the moment – a new decade, a new direction, lots of excitement…and drugs!

Hollywood mainstream movies in the 1990s were by and large just an extension of the 1980s – macho action thrillers (The Rock, Con Air), blockbuster disaster films (Titanic, Armageddon), sequels (Terminator 2: Judgement Day, Back to the Future III, Beverly Hills Cop III), rom-coms (Pretty Woman, Sleepless in Seattle) and cheesy kids entertainment (Home Alone, Free Willy). The first half of the decade saw a Renaissance in Disney animated features (Aladdin, The Lion King, Toy Story) and the latter half of the decade saw a revitalisation of the slasher movie thanks to Scream. But besides that, the one thing that became noticeably new in adult film throughout the world (including Hollywood) was the depiction of drugs, and this reflected in societal changes during the decade as drugs became more widely available and more casually used.

Not all drug films were great, and many displayed a reckless glamourisation of their use, thus overlooking the real-life impacts they could potentially have. But the films of note that gave drugs a ruminative treatment are rightfully established as must-watches even now: The Basketball Diaries had an impressive teenage Leonardo DiCaprio freefalling into heroin addiction on the streets of New York; Clockers, a Spike Lee joint, explored the misadventures of a young man (Mekhi Phifer) selling crack cocaine in a Brooklyn housing project; the notorious Kids, written by Harmony Korine, made it clear that young teenagers in New York were being introduced to all types of drugs and willingly partaking in them (amongst other things); Danny Boyle gave us the quintessential movie of the nineties with Trainspotting, a thoroughly enjoyable thrill-ride set in the decaying suburbs of Edinburgh, where heroin destroys people’s lives and creates opportunities for others; and Sam Mendes’ American Beauty progressively depicts the use of cannabis in treating onsetting depression (a long journey from Reefer Madness to here!)

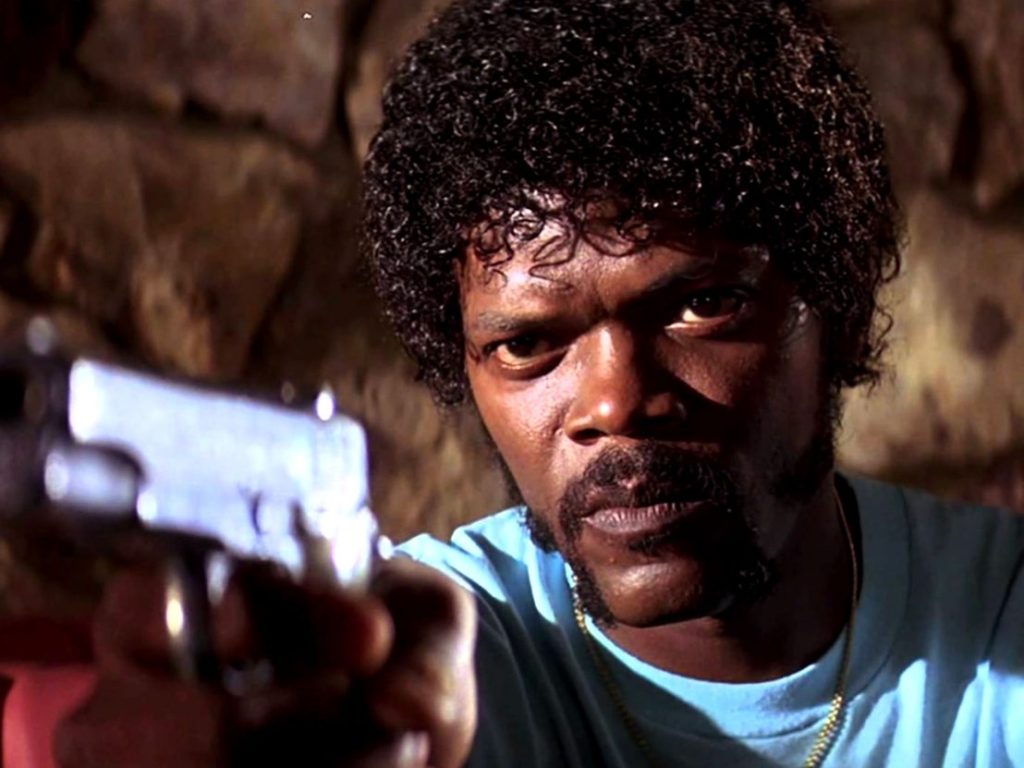

It was not only the casual depiction of drugs that was giving parents nightmares. Sex, violence, and all manners of other extremities were becoming more commonplace in film in the 1990s. Quentin Tarantino may gleefully take some credit for this – his films Reservoir Dogs and Pulp Fiction basically established a new and exciting form of cinematic language, one that was blood-splattered, bravado-filled, impressively witty, and oozing with cool. These films inspired others to take the same tack e.g., Oliver Stone adapted Tarantino’s own story for his brutal and insanely over-the-top Natural Born Killers and made a tidy profit (although Tarantino later disowned the film, and rightly so…I think it is an awful mess). In terms of explicit sexual content, Paul Verhoeven famously went to the extreme with his successful neo-noir crime sizzler, Basic Instinct – a film that established Sharon Stone as a superstar, but also became an example of how female actors were exploited in order to depict a ludicrous, unrealistic, male sexual fantasy. Remembering that this was a time when the Harvey Weinsteins of this world flourished in Hollywood – the spate of subsequent male-written, male-directed psycho-sexual erotic thrillers that came after this film are very gross in this context (listen to Karina Longworth’s stunningly researched series on her You Must Remember This podcast to delve further).

The explicitness of all sorts of material became more prevalent as the decade wore on. David Cronenberg’s Crash, an adaptation of J.G. Ballard’s controversial novel, explored the bizarre fetishism of sex and car crashes. Michael Haneke’s Funny Games brought Hitchcockian manipulation to new levels by basically ‘imprisoning’ viewers and forcing them to witness a sadistic house invasion. Todd Solondz brilliantly, but disturbingly, tackled paedophilia amongst other taboos in Happiness. Lars von Trier consciously utilised the Dogme 95 Manifesto to produce bucketloads of controversial material (mostly pornographic), exemplified best/worst by his dark and tasteless ‘comedy’ The Idiots. In Japan, a flourish of horror films spouted forth after the success of Hideo Nakata’s Ring, and one of those was Takashi Miike’s Audition, which gave the world one of the most shock-inducing torture scenes in film history. Even in more mainstream film explicit violence was being shown uncensored, as in Mel Gibson’s grand-scale medieval epic, Braveheart. Extreme Cinema was becoming a thing and the new Millennium would see movies extend even further in this direction.

But enough of that. What films from the 1990s were worth their salt? Lots were, indeed. This was the decade that saw the Coen Brothers reach cinematic greatness with Fargo and The Big Lebowski. We saw the rise of independent American cinema, which involved the works of rising talents including Todd Haynes, Sofia Coppola, Paul Thomas Anderson, Wes Anderson, Gus Van Sant, Spike Jonze and Kelly Reichardt. David Fincher explored irresistibly beautiful but dark material in two of the most defining films from the era, Se7en and Fight Club. Tim Burton continued where he left off with his stylistically bizarre but empathetic worldview with the likes of Edward Scissorhands, The Nightmare Before Christmas and Mars Attacks! The Australian Peter Weir utilised the superstardom of rubber-faced comic talent Jim Carrey to convey some very relevant concerns about our existential path in the satisfying The Truman Show. And although some may argue against its overly melodramatic tendencies, I hold a lot of admiration for Kevin Costner’s historical epic Dances with Wolves, considering its serious treatment of Indigenous Americans. And finally, the magnificently slick and utterly distinctive futuristic blockbuster from the Wachowskis, The Matrix, came aptly at the end of the decade, when there was a widespread trepidation for what might happen at midnight on December 31st 1999 – obviously we needed to just take Prince’s advice and continue partying!

Beyond the US, the 90s showcased a lot of burgeoning international talent. Mathieu Kassovitz took to the streets of Paris to viscerally portray the everyday brutality experienced by young immigrants and minorities in La Haine. In sunny contrast, Nanni Moretti gave us a wonderfully reflective and personal feature, Caro Diaro, where he spends most of his time riding the streets of Rome on his Vespa. In the fantastically frenetic German experimental thriller, Run Lola Run, the striking, crimson-haired Franka Potente does exactly what it says on the tin – she runs. Wim Wenders took to the colourful streets of Havana to bring together the legends of Cuban jazz in his marvellous documentary Buena Vista Social Club. Ireland had a purple patch in filmmaking with the gifted Jim Sheridan and Neil Jordan offering us gems like The Field, In the Name of the Father, The Crying Game and The Butcher Boy. Chinese cinema soared in the 1990s with its so-called ‘Fifth Generation’ of directors: examples include Raise the Red Lantern and Farewell My Concubine. Asia and the Middle East produced a lot of great films throughout the decade: Xich Lo/Cyclo from Vietnam, Happy Together, an international production from Hong Kong, Hana-bi from Japan, and Gabbeh, Through the Olive Trees, and The White Balloon all from Iran. Additionally, the Taiwanese director Ang Lee moved to the US in the early 1990s making the excellent rom-com The Wedding Banquet (in Mandarin), and followed it up with the equally excellent drama The Ice Storm (in English).

Creativity from around the world was fresh and exuberant, and films from the decade which feature in the Sight and Sound critics’ list of the Greatest Films of All Time Top 100 is very reflective of this:

- Yi Yi (1999, Edward Yang) (=90)

- Chungking Express (1994, Wong Kar Wai) (=88)

- Sátántangó (1994, Béla Tarr) (=78)

- A Brighter Summer Day (1991, Edward Yang) (=78)

- GoodFellas (1990, Martin Scorsese) (=63)

- Daughters of the Dust (1991, Julie Dash) (=60)

- The Piano (1992, Jane Campion) (=50)

- Beau Travail (1998, Claire Denis) (7)

So, no room for Slacker, Dead Man, Silence of the Lambs, Hearts of Darkness: A Filmmaker’s Apocalypse, The Fifth Element, or most surprisingly, Pulp Fiction then? Its ok, I digress. By now, I have reconciled that there are only 100 places in this list and you can’t have them all! So, in addition to what I have discussed above, here are my five favourites from the decade:

Safe (1995, Todd Haynes)

It was reported that people walked out of this film’s premiere at the Sundance Film Festival because they were overly perplexed by the content. The film, particularly its ending, is still debated and criticised by the overly perplexed to this day. Actually, I find Safe to be an incredibly intelligent and deeply engrossing treatise about disease, the human condition and modern America. It was way ahead of its time, and is still very relevant for today’s audiences (obviously, with Covid). Julianne Moore plays a softly-spoken, wealthy Californian housewife called Carol White, who, after experiencing a series of worrying reactions to her (very urban) environment, collapses. With her husband unexplainably absent, she seeks both medical and psychiatric assistance, but no diagnosis nor help is forthcoming and she becomes increasingly isolated in her so-called comfortable surrounds, eventually leaving for a New Age ranch in the desert.

This was not a usual psychological drama or thriller of the ilk that was relentlessly produced by Hollywood at the time. Todd Haynes established himself as a mindful examiner of American social issues with this, his second but first acclaimed feature. Carol’s condition is one that is not easily understandable (technically it is ‘multiple chemical sensitivity’), but Haynes tackles its core from an unorthodox angle. He carefully examines whether the condition is all psychological and then explores the expensive self-help practices available for those going through it. As a gay man who lived through the AIDS crisis in the 1980s, Haynes remembered only too well the patronising, hypocritical and divisive rhetoric around the disease. The experiences of Carol, who is by no means a straight-forward character, lives in the shadow of these experiences. Moore is extraordinary here, and her performance in addition to Haynes’ placement of her character in a hostile, endlessly humming, post-industrialised landscape is what makes Safe an absolute stand-out and potent film of the decade.

Secret & Lies (1996, Mike Leigh)

When I was younger and not as entrenched in movies as I am now, I remember hearing a prominent Irish film and music critic describe Secrets & Lies as the best film he had ever seen. It took me a long time to finally watch it, but boy, was it a joy the first time I did, and its high standing with this critic is definitely justified. Mike Leigh, with his history working in British Television, has a masterful ability to capture the common everyday realities of working-class Britons. He also has a dab hand at getting the best out of his actors. Those two factors are displayed powerfully in Secrets & Lies, arguably his greatest ever achievement. It is a perfect film, with sometimes difficult, sometimes beautiful content. In many ways, the story is set up as a run-of-the-mill soap opera but the way in which Leigh manages it, and his actors perform in it, creates an emotional attachment for the viewer, which in the end (that unforgettable and deeply realistic climax) is massively satisfying.

Marianne Jean-Baptiste plays the wonderfully named Hortense, a young professional black woman who is seeking out her biological mother in modern-day London. To her surprise, she finds her mum to be an embattled, factory-working white woman called Cynthia (played with breathless brilliance by Brenda Blethyn). There is much drama attached to Cynthia’s life: her other twenty-something daughter lives with her and is nothing but trouble, and her younger photographer brother (Timothy Spall) lives close by but because his middle-class wife dislikes Cynthia, they rarely meet. The revelation of her long-lost daughter becomes another drama for Cynthia, who at first refuses to believe it but then strikes up a sweet bond with her, albeit a secretive one. The content is by some token a harsh reflection on British society, but the film possesses a profound heart, and all the characters have redeeming qualities. You think that it is all going to come crashing down at any moment, but a grounding of humanity ensures that it does not.

Princess Mononoke (1997, Hayou Miyazaki)

It is often difficult to pick the best Miyazaki/Studio Ghibli animation given the incredible consistency he maintained during his career. I adore them all, not one of them would I speak ill of. But Princess Mononoke easily fits the mould of one of my favourite films of all time. It is so good that I am sometimes at a loss in describing how good it is. But I’ll try: the animation is astonishingly vivid; the characterisations are rich and relatable; the story is entertaining, profound and fully realised; the themes are relevant to everyone and they are powerfully communicated without being preachy. Miyazaki’s film is a testament to the human imagination. It serves a higher purpose in that it educates as much as it entertains. Having already given us equally brilliant, similarly themed animations in the 1980s (Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind and Laputa: Castle in the Sky), the Japanese Master was building up to this masterpiece. Princess Mononoke is an epic tale about humanity’s relentless push towards economic progress at the expense of nature and the earth itself, and he doesn’t shy away from offering solutions.

The film is set in an alternative medieval Feudal Japan, where the world of humans lives alongside the fantastical world of gods and spirits. Ashitaka is a young warrior assigned to protect his village, when he is injured in a fight with a rampaging and possessed boar. He is told by a wise woman that all is unwell in the balance between man and nature and he must travel west to figure out what has happened and cure his fatal injury. Along the way he encounters an army led by the determined Lady Eboshi, who have just been ambushed by giant wolves. He soon learns that Eboshi is destroying the forests for her mines and creating weapons to defend her people against the hostile forest creatures, who themselves are fighting back because their homes are being destroyed. The wolves are abetted by San, who was abandoned as a child and then raised in the woods, developing a vengeful disdain towards humans over time. Ashitaka reasons with San to join forces and try and restore the balance. The story is full of challenge, heart and nuance. Eboshi makes a point about her actions, as do her people who support her because she provides for them. She is fighting the patriarchy, but her feelings for the forests leave a lot to be desired. San understandably possesses a desire to destroy Eboshi, but is won over by Ashitaka’s pacifist quest for reconciliation. She falls for him as he does her, but her love for the forest is great also. As always with Miyazaki, he creates a stunning and believable universe. One’s heart sometimes stops beating with the level of mastery on show.

The Wind Will Carry Us (1999, Abbas Kiarostami)

There is a wonderful thing that cinema can do – it can bring you to places in the world you would not normally see or know about. Iranian filmmaker and photographer Abbas Kiarostami granted us the pleasure of ogling at the hills of his home country for decades. No doubt a country defined in the West for its politics and oppressive regimes, Kiarostami walked a fine line in making films of artistic merit without delving too deep into social injustices (he would not get his films made otherwise – still, many of them were never shown there). But in his masterpieces from the late 1980s through to the early 2000s, he produced effortlessly beautiful films that laid out ambiguous and enigmatic content within a general non-narrative structure. With The Wind Will Carry Us, Kiarostami arguably gave us the best showcase of his talents.

The story is basic – an engineer arrives in a remote community of Iran and is hosted as a special guest as he is brought on a tour around the place. He meets several locals and notices that they are preparing for the death of an old woman. He also understands a telecommunications pipeline is being built nearby. It later transpires that the engineer is secretly a journalist (perhaps Kiarostami himself) examining the death rituals of the community, and as the woman remains alive, he stays there for much longer than he anticipates. Everything is presented poetically, lyrically, and eloquently. Many characters who speak are never shown, instead the camera is interested in the surrounds – the houses are hives of activities, the fields are bountiful with brightness and colours. Kiarostami ensures that the landscape can speak also. In certain scenes, a person will arrive as a speck within the landscape and then something (or perhaps nothing) will emerge for us to add to the sparse plot. It is a film that is richly rewarding in its immersion as it is in its visuals.

Magnolia (1999, Paul Thomas Anderson)

Magnolia holds a special place in my life. It was the first film for adults that I both enjoyed and (somewhat) grasped in terms of its subject matter, and I think it inspired me to go down the route of more ‘arty’ films ever since. The mosaic, multi-storied film was a feature of the 90s ever since Pulp Fiction, but whereas many were pretentious and not as smart as they thought they were, Magnolia was masterful. Paul Thomas Anderson was clearly a special filmmaker, a man with a vision and the tools to execute it. Magnolia, for me, remains his magnum opus. It takes place over one day in LA and recounts the tribulations of a series of characters, either linked by blood, similarity, or coincidence. The themes vary but a common one emerges around neglectful or abhorrently abusive parents and their deeply resentful children. Anderson’s ability to avoid mundanity as an obvious pitfall here lies in his innate notions of empathy, as well as his perfect eye for cinematic excellence (Altman, Bergman and Welles are clear influences).

The wonderful cast gives Magnolia its hit status, with performances that provided break-outs (Philip Seymour Hoffman), career highs (John C. Reilly, Melora Walters), surprisingly liberated performances (Tom Cruise), swan songs (Jason Robards, Henry Gibson), and comic stand-outs (Luis Guzman, William H. Macy). There are ecstatically funny moments, but there is also emotional intensity. Julianne Moore is incredible as the much-younger wife of a dying former TV mogul – the moment of her breakdown in the pharmacy being a stand-out. Tom Cruise steals every scene he is in, particularly when he holds his dying father’s hand and almost breaks a forehead vain with emotional strain. John C. Reilly’s constantly misplaced reasoning as a do-gooder cop is both hilarious and pathetic, and his besottedness with Melora’s Walter’s drug-addled, deeply troubled character is something we are taken in by. Everything is like an opera, carefully orchestrated but allowed to breathe at moments before being smashed in the face by a random gunshot or a frog falling from the sky. We are never in any doubt we are in a movie, but this is a movie of perfect timing, of unpredictability, of compassion and of human flaws. Aimee Mann’s gorgeous songs were written specifically with the script in mind, and even one of her songs (‘Wise Up’) is sang into the camera by many of the characters. Its delectable from start to finish, every single inch of it.

2 thoughts on “Travelling Through Time: The Best Films of the 1990s”